There are many circumstances and medical diagnoses that may cause an individual to approach the end of their life. The natural aging process and chronic conditions such as heart failure (HF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, and advanced dementia may lead to end-of-life care.

All nursing care should be provided in a holistic, person-centered approach, but during end-of-life care, all caregivers must be fully attuned to the needs and wishes of the person. Caregivers often have a long-standing relationship with the dying person, but it is critical to not assume their client’s preferences. Communication must be more frequent and intentional during end-of-life care because a patient’s needs can change quickly. Additionally, attitudes and mental outlooks often fluctuate for the patient and their loved ones during this difficult time when many decisions need to be made. It is essential for caregivers to find an appropriate balance of interventions and space for the dying person and their loved ones. Use techniques discussed in Chapter 1 for therapeutic communication and making observations of facial expressions and body language to guide your interactions with the resident and their loved ones.

As discussed in Chapter 2.6, “Health Care Settings,” hospice care is a choice offered to individuals approaching end of life. Hospice care is offered to patients who are terminally ill and expected to live less than six months. Hospice provides comfort to the client and supports the family, but curative medical treatments are stopped. It is based on the idea that dying is part of the normal life cycle. Hospice care does not hasten death but focuses on providing comfort.[1] For example, a cancer patient may choose to no longer receive chemotherapy due to its severe side effects but will continue to take medications to manage pain and nausea. While nutritional intake is still important, food choices center around those that are pleasurable to the client rather than meeting their daily requirement of nutrients.

Hospice is a service provided by Medicare and can be delivered in a person’s home or in a facility such as a nursing home or hospital. To qualify for hospice care, a hospice doctor and the client’s primary doctor must certify that the person is terminally ill with a life expectancy of six months or less. The client signs a statement choosing hospice care instead of curative care covered by Medicare. Hospice coverage includes the following:

- All items and services needed for pain relief and symptom management

- Medical, nursing, and social services

- Medications for pain management

- Durable medical equipment for pain relief and symptom management

- Aide and homemaker services

- Physical therapy services

- Occupational therapy services

- Speech-language pathology services

- Social services

- Dietary counseling

- Spiritual and grief counseling for the client and their family

- Short-term inpatient care for pain and symptom management in a Medicare‑approved facility, such as a hospice facility, hospital, or skilled nursing facility that contracts with the hospice agency

- Inpatient respite care, which is care provided in a Medicare-approved facility so the usual caregiver (like a family member or friend) can rest. The client can stay up to five days each time respite care is needed. Respite care can occur more than once but only on an occasional basis.

- Other services that Medicare covers to manage pain and other symptoms related to the terminal illness and related conditions the hospice team recommends[2]

After two physicians agree that a person qualifies for hospice, a nurse from a hospice agency completes an assessment and makes care recommendations. If the client is in a nursing home, their hospice team will coordinate with the facility team to manage the client’s needs and wishes. Visits are scheduled at intervals designated by the hospice team. A hospice nursing assistant may come to the facility to provide cares because they can spend more time with the enrolled hospice client than routinely provided by the facility staff. This extra time can reduce pain that may occur during cares by moving at a slower pace and allowing for periods of rest. The additional social interaction is also beneficial for the hospice client. To improve quality of life, hospice may also provide additional resources such as spiritual chaplains, music therapists, or volunteers who simply visit with the client if they do not have friends or family available.

If a hospice client remains in their own home, the hospice agency provides durable medical equipment like a hospital bed and other items to make caring for the client easier, such as a commode, shower chair, or mechanical lift for moving the client. The hospice nurse and nursing assistant visit regularly based on the needs of the client and their family. The nurse’s or nursing assistant’s visits may also serve as respite, allowing the loved ones a reprieve from caring for the client themselves.

Nursing assistants may choose to work for a hospice agency and receive additional training to better understand and provide end-of-life care.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

End-of-life care often includes unique complexities for the patient, family, and nurse. There may be times when what the physician or nurse believes to be the best treatment conflicts with what the patient or family desires. There may also be challenges related to decision-making that cause disagreements within a family or cause conflict with the treatment plan. Additional challenging factors during end-of-life care include availability of resources and insurance company policies.[3]

Despite these complexities, it is important for the care team to honor and respect the wishes of the patient. Despite any conflicts in decision-making among health care providers, family members, and the patient, the team must always advocate for the patient’s wishes. If a nursing assistant notices conflicts or is questioned by the client or family members, they should notify the nurse. Nurses have practice guidelines for ethical dilemmas in the American Nurses Association’s Standards of Professional Nursing Practice and Code of Ethics. These resources assist the nurse in implementing expected behaviors according to their professional role as a nurse.[4]

If complex ethical dilemmas occur, many organizations have dedicated ethics committees that offer support, guidance, and resources for complex ethical decisions. These committees can serve as support systems, share resources, provide legal insight, and make recommendations for action. The nursing assistant should always include their supervisor in any questionable situation and feel supported in raising concerns within their health care organization if they believe an ethical dilemma is occurring.[5]

Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Advanced Directives

Additional legal considerations when providing care at the end of life are do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and advance directives.

Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders

A Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) order is a medical order that instructs health care professionals to not perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if a patient’s breathing stops or their heart stops beating. CPR is emergency treatment provided when a patient’s blood flow or breathing stops and may involve chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing, electric shocks to restart the heart, breathing tubes to open the airway, or cardiac medications.

A DNR order is written with permission by the patient (or the patient’s health care power of attorney, if activated). Ideally, a DNR order is set up before a critical condition occurs. A DNR order is recorded in a patient’s medical record and only refers to not performing CPR and does not affect other care. Wallet cards, bracelets, or other DNR documents are also available for individuals to have at home or in nonhospital settings.

The decision to implement a DNR order is typically very difficult for a patient and their family members to make. Many people have unrealistic ideas regarding the success rates of CPR and the quality of life a patient experiences after being revived, especially for patients with multiple chronic diseases. For example, a recent study found the overall rate of survival leading to hospital discharge for someone who experiences cardiac arrest is about 10.6 percent.[6]

Nurses can provide up-to-date patient education regarding CPR and its effectiveness based on the patient’s current condition and facilitate discussion about a DNR order. Nursing assistants can provide CPR based on their scope of practice within their state. If a nursing assistant witnesses a cardiac event, their first action should be to notify the nurse.[7]

Advance Directives

Advance directives include the health care power of attorney (POA) and living will. The health care POA legally identifies a trusted individual to serve as a decision-maker for health issues when the patient is no longer able to speak for themselves. It is the responsibility of this designated individual to carry out care actions in accordance with the patient’s wishes. A health care POA can be a trusted family member, friend, or colleague who is of sound mind and is over the age of 18. They should be someone who the patient is comfortable expressing their wishes to and someone who will enact those desired wishes on the patient’s behalf.[8]

The health care POA should also have knowledge of the patient’s wishes outlined in their living will. A living will is a legal document that describes the patient’s wishes if they are no longer able to speak for themselves due to injury, illness, or a persistent vegetative state. The living will addresses issues like ventilator support, feeding tube placement, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and intubation. It is a vital means of ensuring that the health care provider has a record of one’s wishes. However, the living will cannot feasibly cover every possible potential circumstance, so a health care power of attorney is vital when making decisions outside the scope of the living will document.[9]

A financial power of attorney may also be appointed to manage the client’s money matters when they are no longer able to do so. The financial POA can be the same person as the health care POA or a different individual. The financial POA may be enacted independently of the health care POA, meaning that the client can still make their own health care decisions even if their finances are controlled by their designee. The client should select both POAs when they are still able to make sound decisions. Two physician signatures are required to enact each POA to avoid a conflict of interest and ensure the client truly cannot make appropriate decisions. If a client has not filed these legal documents and is deemed incompetent, a state guardian will be appointed as their financial and health care POA.[10]

Signs of Impending Death

As a person nears dying there are several notable physiological changes, especially with circulation, breathing, intake, and appearance of skin. The heart rate will slow and blood pressure lowers, creating cool extremities that may appear cyanotic (blue), pale, or dark. Respirations may become very irregular, referred to as Cheyne-Stokes breathing. Cheyne-Stokes respirations can be observed as gaps in breathing of several seconds, and long and labored or quick and shallow inhalation and exhalation. There may be gurgling or rattling of the lungs when breathing. Intake will decrease and eventually stop altogether, and output will follow the same pattern. Mottling, which looks like severely wrinkled and purple-bluish color skin, often occurs in dependent areas or lower legs and feet.

At some point, the dying person becomes unresponsive, which often leads to the jaw opening. Although the dying person may no longer communicate, hearing is the last sense to fail. It is critical that caregivers continue to talk to the dying person as if they were alert and able to understand.

Care for the Dying Person

Because the end of life is a very emotional time, the person needs to be supported and involved in their care as much as possible to maintain their sense of control. Interventions should center on quality of life and comfort measures. Another important aspect is including loved ones. Their level of involvement should be discussed with the client at an appropriate time when they are able to communicate and understand the conversation. In a long-term care facility, the care team has this conversation with the resident, and it is implemented into the care plan for the nursing assistant to carry out.

Attention to pain is very important. Notify the nurse 10-15 minutes before you plan on providing care so they can assess the resident’s pain and determine if pain medication is needed prior to assisting the resident.

Repositioning should occur hourly due to decreased circulation and a high risk for skin breakdown. Incontinence care and all other hygiene should be completed in bed, and their skin should continue to be moisturized. Massage can help with circulation if it is tolerated by the resident. Due to the jaw opening and breathing with the mouth open, oral care using a moist swab should be done hourly. Consider applying lip balm or other moisturizer at the same time.

The room should be quiet, and lighting should be lowered to the resident’s comfort level. Scents from flowers, deodorizer, or perfumes may be more irritating than normal and should be avoided. Visiting times, as well as the amount of people in the room, may be determined by the nurse. A private area with refreshments away from the resident room should be available for loved ones to gather and rest as needed.

Be aware that hearing is the last sense to go. Explain to the patient what you are doing before you do it and be conscientious of the words being used near the patient. Encourage family members and staff members to talk to the patient even if they are not responding; talking can be comforting to the patient, family members, and caregivers.

Stages of Grief

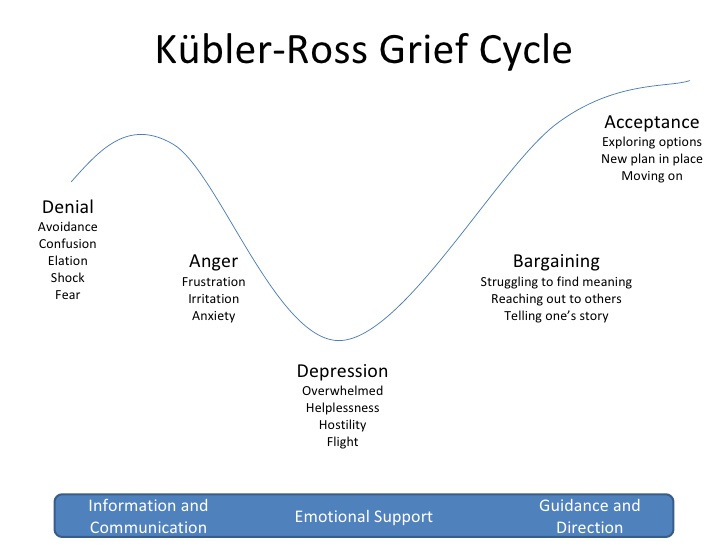

There are several stages of grief that may occur due to any major life change, including end of life and death. It is helpful for caregivers to have an understanding of these stages so they can recognize the emotional reactions as symptoms of grief and support patients and families as they cope with loss. Famed Swiss psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler-Ross identified five main stages of grief in her book On Death and Dying. Patients and families may experience these stages along a continuum, move randomly and repeatedly from stage to stage, or skip stages altogether. There is no one correct way to grieve, and an individual’s specific needs and feelings must remain central to care planning.[11]

Kuber-Ross identified that patients and families demonstrate various characteristic responses to grief and loss. These stages include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, commonly referred to by the mnemonic “DABDA.” See Figure 6.10[12]for an illustration of the Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle. Keep in mind that these stages of grief not only occur due to loss of life, but also due to significant life changes such as divorce, loss of friendships, loss of a job, or diagnosis with a chronic or terminal illness.[13]

Denial

Denial occurs when the individual refuses to acknowledge the loss or pretends it isn’t happening. This stage is characterized by an individual stating, “This can’t be happening.” The feeling of denial is self-protective as an individual attempts to numb overwhelming emotions as they process the information. The denial process can help to offset the immediate shock of a loss. Denial is commonly experienced during traumatic or sudden loss or if unexpected life-changing information or events occur. For example, a patient who presents to the physician for a severe headache and receives a diagnosis of terminal brain cancer may experience feelings of denial and disregard the diagnosis altogether. See Figure 6.11[14] for an image of a person reacting to unexpected news with denial.

Anger

Anger in the grief process often masks pain and sadness. The subject of anger can be quite variable; anger can be directed to the individual who was lost, internalized to self, or projected toward others. Additionally, an individual may lash out at those uninvolved with the situation or have bursts of anger that seemingly have no apparent cause. As a nursing assistant, you may possibly be the target of someone’s projected anger. Health care professionals should be aware that anger may often be directed at them as they provide information or provide care. It is important that health care team members, family members, and others who become the target of anger seek to recognize that the anger and emotion are not a personal attack, but rather a manifestation of the challenging emotions that are a part of the grief process. It often comes from a loss of control in the situation and a feeling of helplessness or hopelessness. If possible, the nursing assistant can provide supportive presence and allow the patient or family member time to vent their anger and frustration while still maintaining boundaries for respectful discussion. Rather than focusing on what to say or not to say, allowing a safe place for a patient or family member to verbalize their frustration, sorrow, and anger can offer great support. See Figure 6.12[15] for an image of a patient experiencing anger.

Bargaining

Bargaining can occur during the grief process in an attempt to regain control of the loss. When individuals enter this phase, they are looking to find ways to change or negotiate the outcome by making a deal. Some may try to make a deal with God or their higher power to take away their pain or to change their reality by making promises to do better or give more of themselves if only the circumstances were different. For example, a patient might say, “I promised God I would stop smoking if He would heal my wife’s lung cancer,” or “I’ll go to church every week if I can be healthy again.” There may also be thoughts such as “Why isn’t this happening to me instead of my child?”

Depression

Feelings of depression can occur with intense sadness over the loss of a loved one or the situation. Depression can cause loss of interest in activities, people, or relationships that previously brought one satisfaction. There is no pleasure or joy surrounding anything. Additionally, individuals experiencing depression may experience irritability, sleeplessness, and loss of focus. It is not uncommon for individuals in the depression phase to experience significant fatigue and loss of energy. Simple tasks such as getting out of bed, taking a shower, or preparing a meal can feel so overwhelming that individuals simply withdraw from activity. In the depression phase, it can be difficult for individuals to find meaning, and they may struggle with identifying their own sense of personal worth or contribution. Depression can be associated with ineffective coping behaviors, and nursing assistants should watch for signs of self-medicating through the use of alcohol or drugs to mask or numb depressive feelings. Any remarks made about feeling depressed or talk of self-harm should be reported immediately. Other symptoms to report include noticed changes in behavior such as isolation or withdrawal from activity, sleeping more or less, and decreased interest in hygiene and self-care. Further discussion about depression can be found in Chapter 10. See Figure 6.13[16]for an image of an individual demonstrating feelings of depression.

Acceptance

Acceptance refers to an individual understanding the loss and knowing it will be hard but acknowledging the new reality. The acceptance phase does not mean absence of sadness but is the acknowledgement of one’s capabilities in coping with the grief experience. In the acceptance phase, individuals begin to re-engage with others, find comfort in new routines, and even experience happiness with life activities again. This may be observed by a person saying, “I want to make the most of the time I have left by spending it with my family” or “I’d like to plan the arrangements for my funeral” or “I know this will be painful and difficult, but I will be okay with the supports I have.” See Figure 6.14[17] of an image representing an individual who has reached acceptance of the new reality related to his loss.

Assisting in the Grieving Process

As already discussed, the grieving process is different for each individual and is not easily predicted. The best action for the caregiver is to listen closely and offer support to the individual. Other possible interventions for the NA to assist with the grieving process are described in Table 6.6.

Table 6.6 Suggested Actions by the Nursing Assistant According to the Client’s Stage of Grief

| Stage of Grief | Suggested Actions by the Nursing Assistant |

|---|---|

| Denial |

|

| Anger |

|

| Bargaining |

|

| Depression |

|

| Acceptance |

|

If the dying client lives in a facility, it is important to consider how their death may affect other residents, as well as the staff members. Some facilities may offer grief counseling that includes sharing thoughts, feelings, or memories of the deceased in a group or individual setting. A memorial service may be held at the facility for residents and staff separate from the family’s plans. Staff and residents will also work through the grieving process, so offering the same interventions as listed above is warranted. Additionally, it is good to promote self-care by maintaining adequate nutritional intake and sleep.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Ouellette, L., Puro, A., Weatherhead, J., Shaheen, M., Chassee, T., Whalen, D., & Jones, J. (2018). Public knowledge and perceptions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): Results of a multicenter survey. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 36(10), 1900-1901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.103 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Kubler-ross-grief-cycle-1-728.jpg” by U3173699 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Young-indian-with-disgusting-expression-showing-denial-with-hands-42509-pixahive.jpg” by Sukhjinder is licensed under CC0 ↵

- “Child's_Angry_Face.jpg” by Babyaimeesmom is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Depressed_(4649749639).jpg” by Sander van der Wel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- “Contentment_at_its_best.jpg” by Neha Bhamburdekar is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

Provides comfort to the client and supports the family, but curative medical treatments are stopped.

A medical order that instructs health care professionals to not perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if a patient’s breathing stops or their heart stops beating.

Emergency treatment provided when a patient’s blood flow or breathing stops and may involve chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing, electric shocks to restart the heart, breathing tubes to open the airway, or cardiac medications.

Include the health care power of attorney (POA) and living will.

Identifies a trusted individual to serve as a decision-maker for health issues when the patient is no longer able to speak for themselves.

A legal document that describes the patient’s wishes if they are no longer able to speak for themselves due to injury, illness, or a persistent vegetative state.

A bluish discoloration of the skin.

Gaps in breathing of several seconds, and long and labored or quick and shallow inhalation and exhalation.