There are four steps in the digestive process. The first step is ingestion, the intake of food into the digestive tract. Ingestion may seem a simple process, but it includes smelling food as it is prepared and served, thinking about food and making food choices, and the involuntary release of saliva in the mouth to prepare for food entry. After food enters the mouth, the next steps of mechanical and chemical digestion of food begin. Mechanical digestion starts with chewing when teeth crush and grind large food particles into smaller pieces that are easy to swallow. Chemical digestion of food involves enzymes found in saliva that break down particles into smaller components.[1]

In the mouth, saliva provides lubrication and enables food to move downward through the esophagus (a muscular tube that goes from the mouth to the stomach). This slippery mass of partially broken-down food is called a bolus that moves down the digestive tract after it is swallowed. Swallowing is initially voluntary because it requires conscious effort to push the food with the tongue back towards the throat, but then it proceeds involuntarily through the gastrointestinal tract, meaning it proceeds without conscious control.

As the bolus is swallowed, it is pushed from the mouth through the pharynx (i.e., throat) and into the esophagus. As the bolus travels through the pharynx, a small flap called the epiglottis closes to keep food from going into the trachea and down into the lungs. Peristaltic contractions in the esophagus (referred to as peristalsis) propel the bolus down to the stomach. At the junction between the esophagus and stomach, there is a sphincter that remains closed until the food bolus approaches. The pressure of the food bolus stimulates the lower esophageal sphincter to relax and open, causing the food to move from the esophagus into the stomach. The mechanical digestion of food continues by the muscular contractions of the stomach and small intestine that mash, mix, and continue to propel the bolus down the digestive tract.[2]

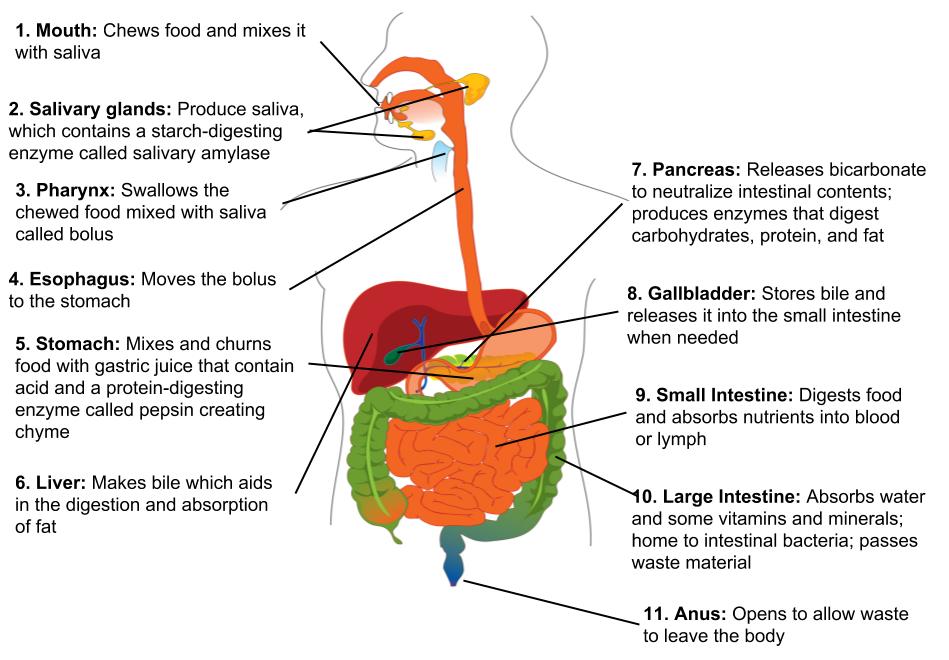

In the small intestine, nutrients are absorbed from the bolus and then transported throughout the body by the cardiovascular system. The small intestine is typically 25 to 30 feet in length with a smaller diameter than the large intestine. After passing through the small intestine, the bolus enters the large intestine. The large intestine is about 8 to 10 feet in length with a larger diameter than the small intestine. Water is absorbed from the bolus in the large intestine, making it solid and formed. It eventually reaches the anus and is expelled as feces.[3] See Figure 11.3[4] for an illustration of digestion.

View the following Khan Academy video for an overview of the digestive process[5]: The Digestive System.

As people age, many age-related changes occur in the digestive system. The condition of one’s teeth (referred to as dentition) often declines during the aging process, resulting in the decreased ability to chew foods with a dense or tough consistency (such as meat and fibrous vegetables). Production of saliva also decreases, increasing the risk for choking. Additionally, many medications cause a side effect of dry mouth that further contributes to the risk of choking. The epiglottis may weaken and allow food or fluids to enter the lungs that can cause aspiration pneumonia. Absorption of nutrients in the small intestine is less efficient, which can cause malnutrition even though food intake may be sufficient. Lastly, the slowing of peristalsis allows the bolus to remain in the large intestine for longer periods of time. As water continues to be absorbed, the fecal matter becomes drier and more difficult to expel, resulting in constipation and possible bowel obstruction.

A bowel obstruction stops the bolus and other digestive contents from reaching the part of the intestine beyond the blockage. The lack of peristalsis that occurs during a bowel obstruction can cause the large intestine to twist upon itself, cutting off circulation and causing tissue death. The area of the intestine experiencing tissue death may require surgical removal. Sometimes the remaining parts of the healthy intestine can be reattached to regain normal bowel function. However, if reattachment is not possible, an opening (called a stoma) is surgically created in the abdominal wall where the healthy part of the intestine is attached. (This type of surgery to create a stoma in the colon is referred to as a colostomy.) Fecal matter is collected in a drainage bag that attaches to the stoma via a device commonly called a wafer. In this manner, elimination occurs through the stoma into a pouch rather than through the rectum. Bowel obstructions, as well as other gastrointestinal conditions such as colon cancer, severe infection, fistulas, or colon injuries, can lead to the placement of a stoma. See Figure 11.4 for an image of a stoma, Figure 11.5[6] for an image of the wafer to which the drainage bag attaches, and Figure 11.6[7] for an image of an attached drainage bag.

The most effective interventions for improving digestive function are to encourage intake of fiber, water, and other fluids, as well as promoting activity as tolerated. Fiber adds bulk to the bolus to keep it moving through the large intestine. Fiber is found in plants, so any food that originates from growing in the ground contains fiber. Examples of high-fiber foods include grains in bread and cereal, rice, barley, quinoa, fruits, and vegetables. Whole grains are preferred because they contain more fiber than processed grains. Water and other fluids aid in peristaltic movement, and activity increases circulation to improve digestive function. See Table 11.3 for common digestive system diagnoses, associated symptoms to report to the nurse, and specific interventions the nursing assistant can implement to promote digestive function. Refer to section Chapter 5.7, “Assisting With Nutrition and Fluid Needs” for additional review of digestive interventions.

Table 11.3 Common Digestive System Diagnoses and Specific Nursing Assistant Interventions[8],[9],[10],[11],[12]

| Diagnosis | Definition | Symptoms to Report | Nursing Assistant Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhoids | Swollen vein(s) in the rectum and anus caused by straining from constipation, during childbirth, or from regular heavy lifting. Risk increases with aging. | Bleeding during bowel movements should be reported to the nurse for follow-up.

If a hemorrhoid becomes strangulated or a clot forms in a hemorrhoid, it can cause severe pain, swelling, inflammation, or a hard lump near the anus and should be immediately reported. |

|

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) | A chronic disorder causing cramping, abdominal pain, bloating, gas, diarrhea, and constipation. Symptoms may be triggered by stress or specific foods. | Increased symptoms. |

|

| Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) | Stomach acid flows back into the esophagus, causing symptoms often referred to as “heartburn.” | Burning sensation in chest, regurgitation of food or sour liquid, or chronic cough. |

|

| Food Intolerance | An inability to digest specific foods. Common food intolerances are lactose intolerance (dairy) or gluten intolerance (wheat). | Increased gas, bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal cramping. |

|

| Food Allergies | An immune system reaction to a specific food that can range from mild to life-threatening. | Immediately report hives (a new rash); swelling of the lips, tongue, or throat; or problems breathing. |

|

- This work is a derivative of Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 ↵

- “Digestive-system-overview.jpg” by Allison Calabrese is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition/chapter/the-digestive-system-2/ ↵

- Khan Academy. (n.d.). The digestive system [Video]. Khan Academy. All rights reserved. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/crash-course-bio-ecology/crash-course-biology-science/v/crash-course-biology-127 ↵

- “Ostomy_wafer_being_worn_by_an_ileostomy_patient.jpg” by Eric Polsinelli (VeganOstomy) is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Ileostomy_2016-09-09_4158.jpg” by Salicyna is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2021, May 12). Hemorrhoids. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hemorrhoids/symptoms-causes/syc-20360268 ↵

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2021, December 1). Irritable bowel syndrome. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20360016 ↵

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2020, May 22). Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gerd/symptoms-causes/syc-20361940 ↵

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2022, March 5). Lactose intolerance. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lactose-intolerance/symptoms-causes/syc-20374232 ↵

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2022, June 16). Milk allergy. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/milk-allergy/symptoms-causes/syc-20375101 ↵

Digestion that begins with chewing when teeth crush and grind large food particles into smaller pieces that are easy to swallow.

Digestion of food by enzymes found in saliva that break down food particles into smaller components.

The muscular tube from the mouth to the stomach.

A slippery mass of partially broken-down food that moves down the digestive tract as you swallow.

The hollow tube that starts behind the nose and ends at the trachea and esophagus.

Flap that covers the trachea and prevents liquids from entering the lungs when swallowing.

The hollow tube, otherwise known as the windpipe, that leads to the lungs.

Contractions that move the bolus through the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine.

A long tube-like organ that connects the stomach and the large intestine where nutrients are absorbed from a food bolus.

The long, tube-like organ that is connected to the small intestine at one end and the anus at the other.

Condition of one’s teeth.

An opening surgically created in the abdominal wall.

A surgically placed opening when a client’s colon function is impaired.