In the past, individuals living with mental health disorders or developmental disorders were viewed as unable to be a part of general society and were often placed in large institutions with little to no access to the outside environment or the community. This unfortunate stigma was due to a vast misunderstanding of these diagnoses. We now know this misconception is detrimental to individuals, and legislative and societal changes have been made to better meet the needs of these individuals. As a health care professional, it is important to understand how you can continue to improve the quality of life in individuals with these diagnoses through your communication, awareness, and approach.

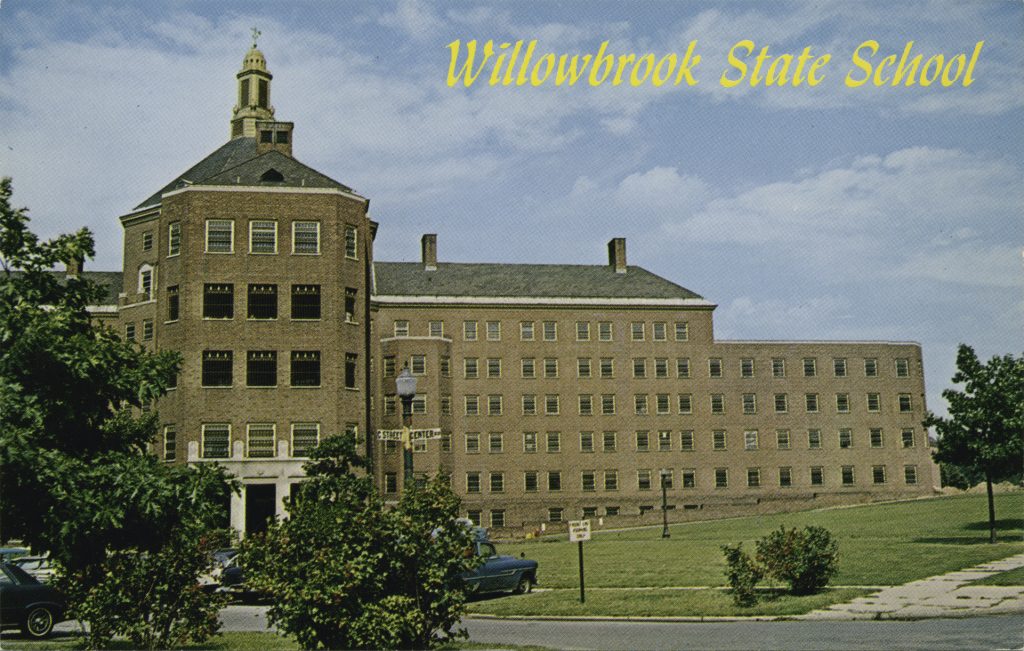

Historically, facilities for institutionalized individuals looked like the Willowbrook State School pictured in Figure 10.1.[1] Residents were typically cared for in large spaces and group settings and eating at long tables with little space for comfort. Often, residents slept in large rooms with several beds in close proximity to each other with no accommodations for privacy or noise reduction. This care environment often caused overstimulation, resulting in sleep disturbances and client behaviors that were difficult to manage. In contrast to current health care practices, individual preferences were not prioritized.

These institutions lacked funding, professional caregivers, and basic knowledge of what residents needed to successfully function to the best of their ability. Because of these conditions, individuals with developmental or behavioral health disorders were often looked down upon, shunned, stigmatized, vilified, criminalized, and, in some cases, imprisoned or tortured. This type of inhumane treatment has been documented as far back as the Middle Ages in Europe and up until the mid-1900s in the United States.[2]

In the United States, this type of care environment continued until 1963 when President John F. Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Act (as seen in Figure 10.2[3]). President Kennedy described this act as “a bold new approach” and provided federal grants to states to construct community mental health centers (CMHC). This act aimed to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and delivery of mental health services to individuals and prevent acute episodes that could impact their safety. In 1965 federal funding was allocated by the Medicaid Act to statewide institutions to improve conditions, staff education, and treatment of residents.[4]

The Community Mental Health Act resulted in a mass “deinstitutionalization” across the country, and by 1980 the population of psychiatric hospitals had decreased by nearly 75%. Deinstitutionalization meant that individuals with behavioral and developmental disorders were cared for in group home settings that allowed for community involvement rather than being isolated in a facility with little or no interaction with general society. By 2009 less than 2% of individuals with mental health disorders lived in a large institution, thus greatly increasing their quality of life, attention to their individualized needs and preferences, and their ability to be active in the community.[5]

Additional consideration has also been given to school-aged children and adolescents with developmental disorders and disabilities to be educated in a mainstream environment. In 1975 the Education of Handicapped Children Act was passed to support special education and related service programming for children and youth with disabilities in public schools. This act mandated that everyone with an intellectual disability was granted equal access to a free education. It was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1990. In 2010 President Barack Obama signed “Rosa’s Law,” which eliminated the term “mental retardation” and replaced it with “intellectual disability.” Deleting this term from legislation helped to change the negative stigma associated with disabilities.

Read the following PDF about Rosa’s Law.

The remaining sections of this chapter will describe common developmental disorders, mental health disorders, and dementias you may encounter as a caregiver.[6]

- “Willowbrook_State_School_(NYPL_b15279351-105038)_-_cropped.jpg” by unknown author is in the Public Domain ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University by Department of Social Work and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “John_F._Kennedy_Signs_the_Community_Mental_Health_Act_-_ST-C376-2-63.jpg” by Cecil W. Stoughton (1920–2008) is in the Public Domain ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University by Department of Social Work and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University by Department of Social Work and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- What is the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act? by University of Washington is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵