Main Body

Melodic Analysis and Composition

Melody is one of the most basic elements of music–we are all sung to as children, and singing is one of the oldest and most important group activities all societies partake in. But the power of melody isn’t in just any string of notes. It’s the notes that catch your ear as you listen; the line that sounds most important is the melody. There are some common terms used in discussions of melody that you will find useful to know. Below are some concepts that are associated with melody.

The Contour of a Melody

A melody that stays on the same pitch has its place in certain styles and techniques, but, overall, we expect melodies to have some change to them. As the melody progresses, the pitches may go up or down slowly or quickly. One can picture a line that goes up steeply when the melody suddenly jumps to a much higher note, or that goes down slowly when the melody falls gradually. Such a line gives the contour or shape of the melodic line. You can often get a good idea of the shape of this line by looking at the melody as it is written on the staff, but you can also hear it as you listen to the music.

Look & Listen!

Arch shapes (in which the melody rises and then falls) are easy to find in many melodies.

Verbal descriptions are helpful in quickly characterizing a melodic shape, for example, you can speak of a “rising melody” or of an “arch-shaped” phrase. You could also describe it as an inverted arch, wavelike, descending, etc. These are generally helpful, but more precise descriptions are needed.

Melodic Motion

Another set of useful terms describe how quickly a melody changes direction–not simply rhythmically, but how large the interval changes are. On the one hand, this can be affected by the rhythm and tempo–whatever shape a melody takes, how fast the notes move is one aspect of describing the changes. However, we also need to describe the space changes, i.e., the intervals.

A melody that rises and falls slowly, with only small interval changes between one note and the next, is conjunct, which means stepwise motion (“joined together”); more specifically, in our notation system, it refers to notes changing by pitch category, A, B, C, etc., or diatonically through the steps of a scale, which could mean a combination of whole or half steps. If you wanted to be even more precise, you could point out when a melodic passage moves chromatically. One may also speak of such a melody in terms of stepwise or scalar motion, since most of the intervals in the melody are half or whole steps or are part of a specific scale.

A melody that rises and falls quickly, with large intervals between one note and the next, is a disjunct melody. One may also speak of “leaps” in the melody. Many melodies are a mixture of conjunct and disjunct motions. (Tip: below, for playback anywhere in the score, click on the note you want to start with and press the play button.)

Look & Listen!

Melodic Phrases

Melodies are broken into phrases; chapter 7 covered how cadences help define and mark off the endings of phrases. A musical phrase is actually a lot like a grammatical phrase. A phrase in a sentence (for example, “into the deep, dark forest” or “under that heavy book”) is a group of words that make sense together and express a definite idea, but the phrase is not a complete sentence by itself. A melodic phrase is a group of notes that make sense together and express a specific melodic “idea”, but it takes more than one phrase to make a complete melody.

How do you spot a phrase in a melody? Just as you often pause between the different sections in a sentence (for example, when you say, “wherever you go, there you are”), the melody usually pauses slightly at the end of each phrase. In vocal music, the musical phrases tend to follow the phrases and sentences of the text. For example, listen to the phrases in the melody of “The Riddle Song” and see how they line up with the four sentences in the song.

Look & Listen!

This melody has four phrases, one for each sentence of the text.

Phrasing and text or no text.

Even without text, the phrases in a melody can be very clear. Without words, the notes are still grouped into melodic “ideas.” Listen to the first strain of Scott Joplin’s “The Easy Winners” (with score) to see if you can hear four phrases in the melody.

One way that a composer keeps a piece of music interesting is by varying how strongly the end of each phrase sounds like “the end,” based on the cadence type. By varying aspects of the melody, the rhythm, and the harmony, the composer gives the ends of the other phrases stronger or weaker “ending” feelings. Often, phrases come in definite pairs, with the first phrase feeling very unfinished until it is completed by the second phrase, as if the second phrase were answering a question asked by the first phrase. When phrases come in pairs like this, the first phrase is called the antecedent phrase, and the second is called the consequent phrase. Listen to antecedent and consequent phrases in the tune “Auld Lang Syne”.

Look & Listen!

The rhythm of the first two phrases of “Auld Lang Syne” is the same, but both the melody and the harmony lead the first phrase to feel unfinished until it is answered by the second phrase. Note that both the melody and harmony of the second phrase end on the tonic, the “home” note and chord of the key.

Of course, melodies don’t always divide into clear, separated phrases. Often the phrases in a melody will run into each other, cut each other short, or overlap (“elision”). These variations keep a melody interesting.

Composing a Melody

One of the best ways to put all of these concepts for Melody–and chords, scales, rhythm, etc.–together is to write a melody. You’ve already been completing smaller projects up to this point, so for the final composition project, you’ll be composing a melody as well as putting an accompaniment with it.

One of the best ways to understand the interaction of chords and melody is to harmonize a melody.

Lecture Video, Basic Harmonization of a Melody:

The inverse of this process is to construct a melody out of a chord progression.

Lecture Video, Creating a Melody from a Progression:

Melodic Minor Scales

In the melodic minor scale, the sixth and seventh notes of the scale are each raised by one-half step (again, borrowed from the parallel minor) when going up the scale (ascending), but return to the natural minor when going down the scale (descending). If you compare the top half of a melodic minor scale to its Parallel Major scale, you’ll see that they are the same notes. Melodies in minor keys often use this particular pattern of ascending and descending accidentals (but not always), so instrumentalists find it useful to practice melodic minor scales in this way, i.e., the ascending and descending patterns.

Listen & Look!

Lecture Video, Melodic Minor:

Non-Chord Tones

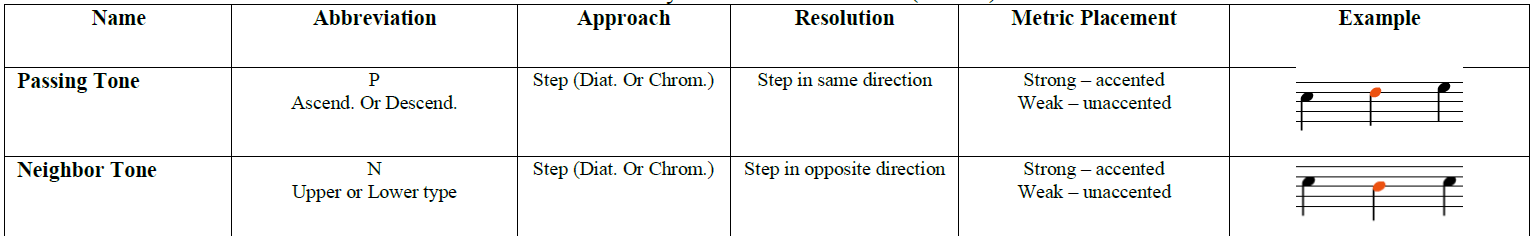

As discussed in the composition project videos, nonchord tones (NCT) are a very common way of embellishing a melody. For this course and project, we will only use the neighbor and passing NCTs–shown below. Typically, there is one NCT between two chord tones; sometimes there can be more than one. In the chart below, the NCT is always shown in orange. The note before the orange NCT tone is the approach tone and the one after is the resolution tone. Each of these notes has their own column, that explains how to go to the NCT and how to leave the NCT (step or leap). There are several other NCTs, and will be covered in the next theory course.

Non-Chord Tones (NCTs)

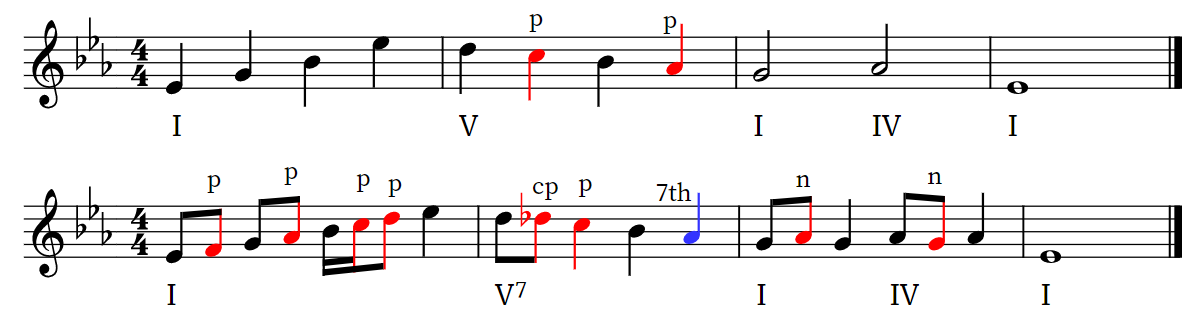

Here is a very simple melody (top system) with a couple passing tones, and then a more elaborate version with several passing (p) and neighbor (n) tones added in for illustration (bottom system).

Look & Listen!

Lecture Video, Embellishing a Melody with Non-Chord Tones:

Performance Practices

As we prepare for your final composition, here are a few applications of how to communicate more specific directions to the performer. What is contained in this chapter are the most practical examples, especially for contemporary use.

Let’s Hear It!

Noteflight–and many other notation programs–can add in all (or most) of the following items, so you can hear the effect they have on the music. The quality of how well any software program can approximate these varies, to be sure, but they give an excellent start on hearing the concepts applied. Remember, that many of the techniques discussed below are instrument dependent in how they are applied by the musician and the effect. If you’re ever writing for real people, it’s always a good idea to talk with someone about it.

Tempo

As discussed in Chapter 3, you’ll want to indicate a tempo for your piece. This is one of the single most important ways of establishing the mood of your piece–how fast it moves communicates a lot. You can find many online metronomes and smartphone app metronomes for free through a search. You can even find “tap” metronomes, where you tap on a digital button and it will tell you the Beats Per Minute (BPM). Mark the BPM at the beginning of your piece.

Dynamics

Sounds, including music, can be barely audible, or loud enough to hurt your ears, or anywhere in between. When they want to talk about the loudness of a sound, scientists and engineers talk about amplitude; musicians talk about dynamics. The amplitude of a sound is a particular number, usually measured in decibels (a physics term), but dynamics are relative to the instrument or voice, the acoustics of the room, whether amplification is used or not. Composers use terms that indicate relative dynamics within the piece, rather than trying to communicate absolutes. While BPM can be precise and easy to setup, dynamics have no practical way to establish the loudness baseline for the musician (short of using a decibel meter, which is not practical at all).

For this reason, traditional dynamic markings–even those based on Italian words–have stuck around. Of course, there is nothing wrong with simply writing things like “quietly” or “louder” in the music. Just be aware, a lot of musicians still use several of these Italian terms. Like many foreign words borrowed into a language, we’ve gotten used to them, and they’ve just “stuck” out of convenience. The most common ones can be found here: https://www.aboutmusictheory.com/music-dynamics.html.

Accents

We first discussed accent with beat grouping in a meter, and then with syncopation. A composer may want a particular note to be louder than all the rest, or may want the very beginning of a note to be loudest. Accents are markings that are used to indicate these especially strong-sounding notes. There are a few different types of written accents but, like dynamics, the proper way to perform a given accent also depends on the instrument playing it, as well as the style and period of the music. Some accents may even be played by making the note longer or shorter than the other notes, in addition to, or even instead of being, louder. (See articulation for more details.) The most common ones can be found here: https://www.aboutmusictheory.com/music-dynamics.html (middle of page).

Articulations

The word “articulation” generally refers to how the pieces of something are joined together. For example, how bones are connected to make a skeleton–joints–is called articulation. How syllables are connected to make a word is similar. Articulation depends on what is happening at the beginning and end of each segment.

In music, the segments are the individual notes of a line in the music–any line of music: melody, inner part, bass, accompaniment. The line might be performed by any musician or group of musicians: a solo singer or a bassoonist, a violin section, or a trumpet and saxophone together. The articulation is mostly about how a note is started and finished. The attack—the beginning of a note—and the amount of space in between the notes are particularly important.

Performing Articulations

Descriptions of how each articulation is done cannot be given here, because they depend too much on the particular instrument that is making the music. In other words, the technique that a violin player uses to slur notes will be completely different from the technique used by a trumpet player, and a pianist and a vocalist will do different things to make a melody sound legato. In fact, the violinist will have some articulations available (such as pizzicato, or “plucked”) that a trumpet player will never see. For our purposes 1) you need to be aware of the wealth of options available to performers and composers; 2) for the composition project, you can try some of the articulations below—Noteflight will give a pretty good approximation!

Common Articulations

Stacatto

Staccato notes are short, with plenty of space between them. That doesn’t mean that the tempo or rhythm goes any faster. The tempo and rhythm are not affected by articulations; the staccato notes sound shorter than written only because of the extra space between them.

Look & Listen!

Legato

Legato is the opposite of staccato. The notes are very connected; there is no space between the notes at all. There is, however, still some sort of articulation that causes a slight but definite break between the notes (for example, the violin player’s bow changes direction, the guitar player plucks the string again, or the wind player uses the tongue to interrupt the stream of air).

Legato is marked by a slur, which is a curved line joining any number of notes. When notes are slurred, only the first note under each slur marking has a definite articulation at the beginning. The rest of the notes are so seamlessly connected that there is no break between the notes. A good example of slurring occurs when a vocalist sings more than one note on the same syllable of text. This is not the same as portamento—“scooping” or “sliding” between notes.

Listen & Look!

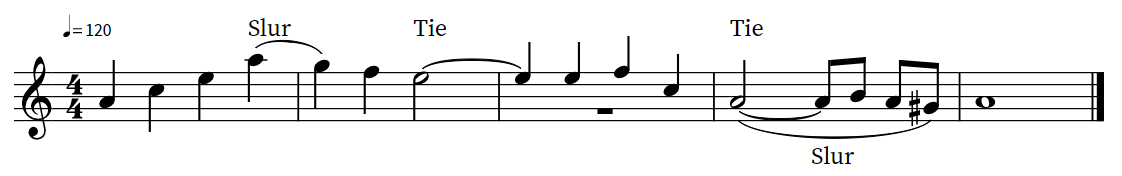

Slur

All notes within the slur are “connected,” so the start of each note is not pronounced.

NOTE: Reminder, a tie (Ch. 3) looks like a slur, but a tie is between two adjacent notes that are the same pitch. A tie is not an articulation marking—it is a rhythm concept. When notes are tied together, they are played as if they are one single note that is the length of all the notes that are tied together. Ties and Slurs actually have nothing to do with one another.

Slur versus Tie

Look & Listen to this example.1) Ties must be two of the same pitch, and must be adjacent. Slurs are different pitches and can connect two or more notes.

2) Notice that individual notes that are not slurred have a noticeable “attack”–articulation–at the start of each note; it’s easiest to hear the difference on the last slur of grouped notes.

A slur marking indicates no articulation—no break in the sound—between notes of different pitches. A tie is used between two notes of the same pitch. Since there is no articulation between them, they sound like a single note that has been extended in value. The first tie above turns the 1/2 note into a dotted 1/2 note that crosses the barline. The last tie connects the 1/8th note to the 1/2 note, lengthening it just slightly, but there is no way to create this with a dot, so the tie is needed.

Here is a more advanced example that shows how slurring affects articulation. Each measure would be played legato (smooth and connected); a pianist would use their finger technique and/or the pedal to achieve this, but a violinist would have to use one bow direction, or motion, for the first measure and a separate direction for the second measure.

Advanced example of a slur.

Watch this sample from Mendelsshon’s Violin Concerto. You can see/hear how the violinist (:51-54) plays multiple notes with only one bow motion, and then at the end of the clip (near :54-56), plays several notes with separate bow motions.