Main Body

Chords and Keys

Harmonic analysis means understanding how a chord is related to the key and to the other chords in a piece of music. This is so practical that you will find many musicians who have not studied much music theory, and even some who don’t read music, but who can tell you what the “one” or the “five” chord are in certain keys.

Why is it useful to know how chords are related? Many standard forms (for example, the “twelve bar blues”) follow specific chord progressions, which are patterns of how chords are strung together in a row.

- If you understand chord relationships, you can transpose any chord progression you know to any key you like, which can make it easier to sing or play.

- If you are searching for chords to go with a melody, it is very helpful to know what chords are most likely in that key, and how they usually progress from one to another.

- Improvisation requires an understanding of the chord progressions.

- Harmonic analysis is also necessary for anyone who wants to be able to compose stylistic chord progressions or to study and understand the music of other composers.

Basic Triads in Major Keys

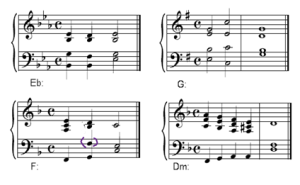

You can find all the basic triads that are possible in a key by building one triad on each note of the scale. One easy way to name all these chords is to number them: the chord that starts on the first note of the scale is “I”, the chord that starts on the next scale degree is “ii”, and so on.

In classical and jazz theory, Roman numerals (hereafter RN) are used to number the chords. Capital RN are used for major chords and small RN for minor chords. The diminished chord is a small RN followed by a superscript circle o. [The augmented chord is a capital RN with a superscript plus + sign, but we aren’t gong to see any of them in the progressions we will use here).

Look & Listen!

To find all the basic chords in a key, build a triad (in the key) on each note of the scale. You’ll find that although the chords change from one key to the next, the pattern of major and minor chords is always the same.

The benefit of RNs is that you can refer to patterns quickly by referencing the RN. Unlike lead sheet symbols, RNs maintain their chord function even when you change keys. This progression of chords: ii V I sounds like the same pattern no matter what key/scale it is in. While RNs started in classical theory, they are also used in jazz theory and discussed by jazz musicians frequently.

Lecture Video, RNs:

Dominant Seventh Chords

If you take a basic triad and add a fourth note on top that is a seventh above the root, you have a seventh chord. There are several different types of seventh chords, distinguished by both the type of triad and the type of seventh interval used. We will only be looking at one type in this course, the Dominant 7th chord.

The Dominant 7th chord is made up of a Major triad and a m7 interval above the root. It is called the dominant 7th because it is constructed on the fifth (dominant) scale degree of a key.

Step 1 is to build a major triad. Step 2, create a minor 7th interval above the root of the major triad.

Scale Degrees and Roman Numerals

- The Dominant 7th chord takes its name from the scale degree it is usually built on (5th note of any major or minor scale). So far, we have only talked about scale degrees with Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3; 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.), but the video below introduces the use of Roman Numerals (I, II, III, etc.) in music, which are reserved for chords.

- The formula is straightforward: scale degree number (1, 2, 3, etc.) = the roman numeral (RN) number for the chord root.

- The reason we switch to roman numerals is to make it easy for musicians to communicate that they specifically mean an entire chord as opposed to just one pitch in a scale.

- We distinguish major chords with a capital RN, e,g., I, IV, V, and minor chords with a lower case RN, e.g., ii, v, vi. Here is the same chart from just above (“Next level chord knowledge) with the RN added. Also, see the “Lead sheet – Roman Numerals” video below, at the end of this section for a brief introduction.

- We will put roman numerals to more use in Chapter 7.

Lecture Video, 7th Chords–Dominant 7th:

Key Takeaways

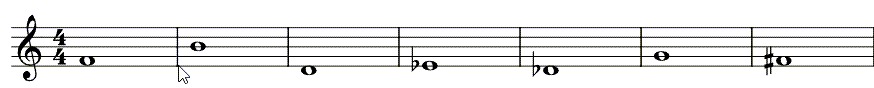

In Chapter 4, we learned about the Natural minor scale, and mentioned that there were some additional types of minor scales. The dominant 7th chords in the examples above, for the minor keys, were built using natural minor. Now is the time to introduce the key element of the Harmonic minor scale: raising the 7th scale degree by one half step, which allows the dominant 7th chord to move from having a minor triad to a major triad, even while used in a minor key.

Look & Listen!

Listen to the difference between v7 (natural minor) and V7 (harmonic minor). It became a tradition starting in the 17th century to most often use the harmonic version. That is still the case mostly today, but pop and jazz music more regularly make use of natural minor v and v7. Notice how the harmonic minor V7 version leads into the tonic chord more strongly.

Concept Check

Example 7-1

Place the correct key signature then complete all of the triads and the V7 for each, and label each with the correct roman numeral.

Bb Major

Eb Major

Concept Check

Example 7-2: Create Dominant 7th chords on the following roots. 1) Build a major triad; 2) build a m7th interval above the root. In steps 1 and 2, do not change the given root pitch.

Naming Chords Within a Key

Thus far, we have concentrated on identifying chord relationships by number, because this system is commonly used by musicians to talk about every kind of music from classical to jazz to blues. The other set of names that is commonly used, particularly in classical music, are the names of the scale degrees, learned in Chapter 4. As we discussed there, these names are associated with functions of scale degrees, and now the chords that go with them. Function refers to how scale degrees as pitches in a melody and as chords set up certain expectations about where a melody and/or a chord progression will go.

Concept Check

Example 7-3: Name the chord.

- Dominant in C major

- Subdominant in E major

- Tonic in G major

- Mediant in F major

- Supertonic in D major

- Submediant in C major

- Dominant seventh in A major

Triads in Minor Keys & Harmonic Minor

In Chapter 4, while discussing parallel minor keys, we learned that a minor scale can be compared with its parallel scale on degree, 3, 6 and 7. Composers like to take advantage of these alterations when constructing chords and melodies in minor keys. Let’s learn about those alterations to chords, called harmonic minor (we’ll learn about the melodic alterations in Chapter 8). Harmonic minor is created by taking natural minor, and raising the 7th scale degree (borrowing it from the parallel major), which raises the 3rd of the V(7) chord, and raises the root of the VII chord; again, this makes these two chords the same as the parallel major chord qualities from major. See the charts and videos below:

Lecture Video, Harmonic Minor:

Lecture Video, Harmonic Minor and the Keyboard:

Using Harmonic Minor for the v, v7, and the VII chords, changing them to V, V7, and viio.

These differences are also covered in the video.

Lecture Video – Minor Key RN [NOTE: Melodic minor starts at 2:42; no need to watch past that point just yet, but feel free. We will cover melodic minor in Ch. 8.]

Concept Check

Example 7-4: Write (triad) chords that occur in the following minor keys–place the key signature first. Place the RN below each, reflecting the correct quality–this exercise is based in Natural Minor–no accidentals.

A Minor

B Minor

Concept Check

Example 7-5: Complete the following using Harmonic minor. Place the RN below each, reflecting the correct quality.

G Minor

C# Minor

Inversions In Context

Lecture Video – Inversions Context (note, this video makes use of the Figured Bass shorthand (5-3, 6-3, etc.), which we are not using, but overall concepts covered are still relevant):

Cadences

Let’s consider this poem, “Names” by Brad Osborne:

If true that a rose by another name

Holds in its fine form fragrance just as sweet

If vivid beauty remains just the same

And if other qualities are replete

With the things that make a rose so complete

Why bother giving anything a name

Then on whom may I place deserved blame

When new people’s names I cannot recall

There seems to be an underlying shame

So why do we bother with names at all

Each line has a sense of “rhythm” and ends with a sense of pause – some stronger than others. The rhyme scheme of the last word also influences our sense of incompleteness or conclusion. If you were reading this out loud, then you would also need to consider where to take a breath. Poetry lends itself to being set to music because of these elements: rhythm, flow, rhyme, segments. Leaving out the punctuation leaves a reading of this poem open to more interpretation. Poetry forms make use of syllable and rhyme schemes, and label portions as lines or stanzas. Music follows similar conventions, and breaks music into phrases, melodies, themes, sections, verses, etc. Phrases are one of the most important form elements in all of music; the sense of pause, conclusion, inconclusion, can be influenced by the lyrics, but not always. Even music with no lyrics will typically have a strong sense of phrasing in the melody. One way to help influence this is with the chords accompanying the melody; at the end of phrases, composers like to use 2-3 chord clichés that signal the end of the phrase called cadences.

Cadences – Look & Listen

Traditional Cadence Formulas:

-

- Authentic: A dominant chord followed by a tonic chord (V-I, or often V7-I).

- Plagal Cadence: A subdominant chord followed by a tonic chord (IV-I). For some people, this cadence will be familiar as the “Amen” chords at the end of many traditional hymns.

- Half Cadence: A cadence that ends on the dominant chord (V); considered incomplete. The chord before—here ii—could be several different chords; the main criteria is that the phrase ends on V.

- Deceptive Cadence: The vi chord is used as a substitute for the I chord (in major or minor key) in what looks like it would be an Authentic cadence.

Listen to these examples of all of the above cadences from Robert Hutchinson’s OER text: https://musictheory.pugetsound.edu/mt21c/cadences.html#AuthenticCadence

(FYI: we use much of Hutchinson’s textbook in music 1A, 1B, and 2A.)

- Here’s a fun summary of the basic cadences, as well as several variations used in pop music.

- Here’s another good summary demonstrated on the piano (his definition of a cadence in the intro. is a little loose, as he’s blending cadences and progressions, but I get that he’s trying to not be too constrictive in the application); I like how he adds in vocal embellishments and song snippets to his explanations.

Concept Check

Example 7-6: Identify the type of cadence in each excerpt. 1) Analyze the leadsheet of each chord; 2) analyze the roman numeral; 3) label the cadence based on the last two chords, compared with the Cadence examples. [Note: Ignore the F pitch in parentheses in the F major example; this would create a minor 7th chord.]

Chord Progressions

Among the seven chords in a key, some are more likely to be used than others. The most common chord is I. In Western tonal music, I is the tonal center of the music, the chord that feels like the “home base” of the music. In major keys, the other two major chords in the key, IV and V are also likely to be very common.

Whereas the I (tonic) chord feels most strongly “at home,” V7 gives the strongest feeling of dissonance. This contrast is typical for giving music a satisfying ending. Although it is less common than the V7, the diminished viio chord, is considered to be a harmonically unstable chord that strongly wants to resolve to I. Listen to this short progression and hear how the I chord is stable and the other chords create various levels of tension compared to it. Listen to these sample progressions:

Look & Listen!

Many folk songs and other simple tunes can be accompanied using only the I, IV and V (or V7) chords of a key, a fact greatly appreciated by many beginning guitar and keyboard players.

A lot of folk music, blues, rock, marches, and even some classical music is based on simple chord progressions, but, of course, there is plenty of music that has more complicated harmonies. Pop and jazz in particular often include many chords with added or altered notes. Classical music also tends to use certain more complex chords in greater variety, and is very likely to use chords that are not in the key (chromaticism).

Pop and Jazz Progressions

Some common progressions:

- Circle of 5ths: Can start on any chord in the key, and then follow a descending 5th motion, for example: IV – viio – iii – vi – ii – V – I

- “ii – V – I” – as you can see, this is a subset of the circle of 5ths, but is very important in jazz.

- Doo-wop: I – vi – IV – V – I

- 4-Chord Axis/Loop/”Money”: I – V – vi – IV – this is used in dozens (more?) of pop songs. It can also start on any of the four chords, and continue from there.

Why are these so popular? Why do these “work”? We dive into the answers to these questions in more depth in Music 1A & 1B, but here are just a few factors to explain some of the progressions:

- Circle of 5ths – this is the basis of many progressions or portions of longer progressions; you can find it by looking for the root motion – it cycles in a falling fifth direction.

- Primary and Substitute Chords: I, IV, V (i, iv, V) are considered the primary chords of any key; their substitutes are vi, ii, and viio, respectively. I can expand a progression, such as I – IV – V – I by swapping and/or adding substitutes to the Doo-wop progression: I – vi – IV – ii – V – I, or I – ii – viio – I, or I – vi – IV – viio – I

- Mixture – borrowing chords between the parallel major and minor of a key. The videos above touch on this, for example, when they mention the “Minor Plagal” that uses iv – I, instead of IV – I. You would get this by lowering the 6th scale degree to change the quality of the IV chord to iv.

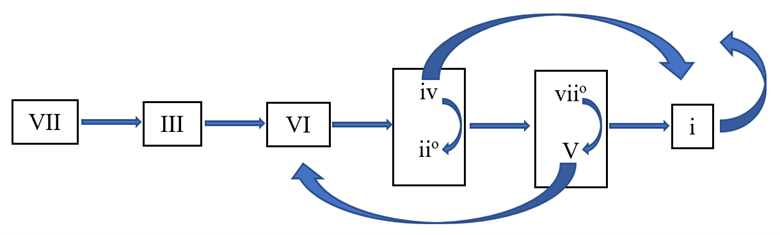

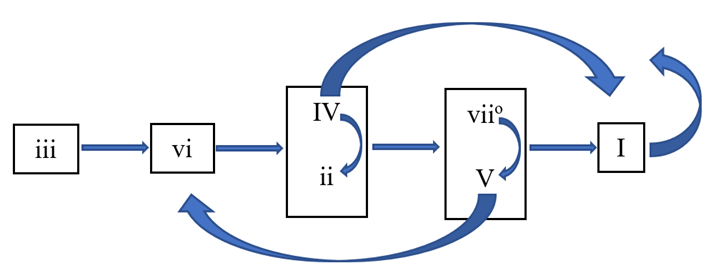

As part of your last composition exercise, you will need to construct a Chord Progression using the following charts. These charts capture the most basic diatonic progressions used in a good amount of music. For someone just starting out, they are helpful in coming up with a basic phrase progression, as you will do in the assignment.

TIP: Most pieces will start on the Tonic (I) chord to help establish the key center. The way these flow charts work is not a simple left-to-right: after starting on I–which is like the Queen piece on a chessboard, it can go anywhere–follow the arrows, which can take you left or right, depending on your current chord, until you complete your progression at a cadence.

Progression flow chart for major keys.

Progression flow chart for minor keys.