Main Body

Scale Types

You’ll remember from our earlier discussion of pitch, clefs, and the keyboard that we only have seven pitch class names: A-G. In order to get 12, we have to use the accidentals. In chapter one, you analyzed the piano white key scales by looking at the half and whole steps for each white octave group: you created a scale starting on each pitch class.

Scale: A group of pitches that follow a certain interval pattern. The order of the pitches is specific only to the “scale form”; once that form is established, the notes can be used in any order to form the building blocks of melodies and harmonies. Scales can have different total numbers of pitches, with most having a minimum of 5 (pentatonic scale) up to 12 (chromatic scale).

Some of those scales from Chapter 1 sounded similar, but with one small difference in each, which you noticed in the arrangement of half and whole steps. Overall, you could group each of them by ear into “brighter” ones (C, F, G) and “somber” ones (D, E, A); the one starting on B was different from either group. You are already likely familiar with the most common scales using the 7 note names in most of the music we know–the “Major” and “Minor” scales. C, F, and G are closer to the major scale type; D, E, and A are closer to the minor scale type; B is in a special category – more later. Sing “Joy to the World,” and you are singing a descending version of the Major scale – try this on C; sing “Greensleeves” (“What Child is This?”), and you are singing the Minor scale – try this with the D scale, but begin with the pitch A (“What..”).

In their pitch-class form (white keys only), these scales represent the 7 “modal” scales. Jazz musicians will recognize these scales. These scales are much older than jazz and go back a couple of thousand years (!) to Greek and early church scales, which were used (in some modified forms) into the 17th century.

Original Greek “Modal” Scale Names

Pitch-Class Scale with older Greek Modal Name.

- C-C: Ionian

- D-D: Dorian

- E-E: Phrygian

- F-F: Lydian

- G-G: Mixolydian

- A-A: Aeolian

- B-B: Locrian

The major and minor scales that we know today are a much later invention, standardized in the 17th century. To make all seven of these modal scales sound like the modern major and minor scales, we need to add some accidentals to make the two patterns uniform. But first, a quick summary of scales, in general.

Lecture Video – Basic of Scales:

Major Scales & Keys

Let’s take a closer look at the Major and Minor scales. As noted above, most people characterize major scales as happy, lighter, brighter and minor scales as sadder, serious, darker. These are subjective, of course, but see if these basic differences jump out at you in the examples below.

Concept Check

Example 4-2: Listen to these excerpts. Can you tell which is which are major and which are minor by listening? Don’t worry if it’s not apparent right away – that’s partly why you’re taking this class!

A)

B)

C)

D)

Major Scale Construction

Let’s look at the details of how to build the Major scale. The C modal scale (Ionian, C to C, all white keys) gives the base pattern for the major scale in half and whole steps:

W W H W W W H

See the Noteflight example below for how this works on the staff, and how we translate it to other starting pitches.

Look & Listen!

All major scales have the same pattern of half steps and whole steps, beginning on the note that names the scale. NOTE: the first pitch of every scale (no matter the type) names the scale (Ab major, D pentatonic, Bb minor, F whole tone, etc.); that first pitch is called the “tonic” scale degree, or just tonic.

Listen to, and sing along with all of the scales in the Noteflight example above. Note that 1) feel and hear the differences between the major version and the modal version; 2) compare all of the major scales: even though range moves higher or lower, the pattern is exactly the same, and therefore the sound of the scale should feel/sound the same (or similar). Don’t worry if it’s not obvious to you right away – give yourself some time if you are new to this; we will be doing drills to help you hear it better.

Diatonic Scales

Take a look back at the Noteflight example to notice the accidentals more carefully: only one type is used in each scale. This is called a diatonic scale, meaning that if the scale has seven pitch classes, then you need to use all seven pitch classes, i.e., you can’t use enharmonic choices. For example, look at the G major scale, which uses an F#. It would be incorrect to spell that like this: G A B C D E Gb G♮ – the reason is that it skips pitch class F. Diatonic scales use the prescribed number of pitch classes as defined in the scale. If they don’t do this, then they are doing what’s called a chromatic variation. The chromatic scale is the scale that uses only half steps, and can have a lot of enharmonic variations (see the appendix for more on the chromatic scale).

Lecture Video – Major Scale Pattern:

Lecture Video, Major Scale on the Keyboard:

Concept Check

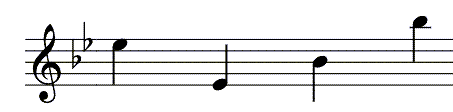

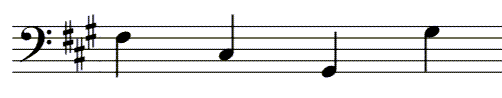

Example 4-3: For each note below, write a major scale, one octave, ascending or descending, as directed, beginning on the given pitch (see the appendix for pitch octave numbers). Remember, Major scales are diatonic, so they must use all 7 pitch classes and can only use one type of accidental (#s or bs).

Begin on F4, ascending ![]()

Begin on G5, descending ![]()

Begin on Ab4, ascending ![]()

Begin on A3, descending ![]()

Begin on Cb3, ascending ![]()

Key Signatures

In the examples above, the sharps and flats are written next to the notes. In common notation, the sharps and flats that belong in the scale will be written at the beginning of each staff, in what is called the key signature. This is a shorthand notation, rather than rewriting the accidentals for every occurrence of a pitch that requires it. Because of this notational device, musicians refer to a scale as a key, and they also refer to a song written using that scale as “in” that key.

The key signature comes right after the clef symbol on the staff. It may have either some sharp symbols on particular lines or spaces, or flat symbols, again on particular lines or spaces. In standard keys, accidentals are never mixed within the key signature. If there are no flats or sharps listed after the clef symbol, then the key signature is “all notes are natural.” Clefs and key signatures are the only symbols that normally appear on every staff. They appear so often because they are such important symbols.

Key Signatures. In the first, all Es and Bs would be played as Ebs and Bbs; in the second, all Fs, Cs, and Gs would be played as F#s, C#s, and G#s. Key Signatures affect all pitches of that pitch class, regardless of octave.

The sharps or flats always appear in the same order in all key signatures. This is the same order in which they are added as keys get sharper or flatter.

Sharps: F C G D A E B Flats: B E A D G C F

(Notice that they are simply the reverse of one another!)

If you want to use a mnemonic device for this, that’s ok; a common one is: Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle and then just reverse it.

On the staff, they look like this – complete key signatures for both clefs, flats and sharp keys. This is the standard way to notate them – do not alter it.

Key Takeaways

1) It’s important to remember that the order does not change: three flats will always begin with B, E, A–you can not have a three-flat major key signature with, say, A, D, G; this is same for the sharps.

2) As a rule, do not repeat the accidentals already in the key signature—this will be confusing to the musician and is extra work for you. However, if a pitch is altered by an accidental to change it from what is in the key signature, then it is standard to place a courtesy accidental, when the note is changed back to the key signature, as a reminder to the player.

3) As explained in the videos below, the order of the sharps and flats in the key signature is NOT the same as you will find them laid going through a scale. This is explained below in the circle of 5th’s video. Key signatures evolved to explain the scales on the circle of 5ths, which explains the order of the sharps and flats in the key signature. Once you know who the sharps or flats are for a particular scale, then you add them as-needed. This also makes sense, because when you create a melody from a scale, the notes from the scale will be all “mixed up” according to how the melody is built, so the order of the sharps or flats doesn’t matter at that point – you just need to know which notes are altered and remember to change them as you perform the melody.

It is very important to memorize the key signatures. It will make your musical life with scales and chords much easier (and for other musical concepts as well). The easiest way to do this is to simply memorize them with flashcards. There are only 15 major keys. That’s it—it’s not like trying to memorize protein synthesis! Many people like to use the circle of 5ths to help memorize; that’s ok, but I still think that it ultimately creates more work, because you have to remember the order of the entire circle–avoid creating layers to your memorization.

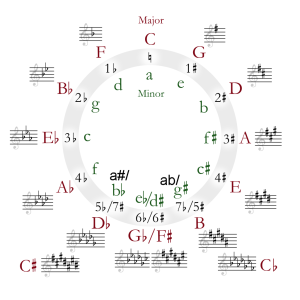

The Circle of 5ths. The Major keys are on the outside (upper case); the Minor keys (discussed later in this chapter) are on the inside (lower case). Notice the overlap of 3 enharmonic keys at 5, 6, 7, o’clock.

Lecture Video, Key Signatures:

Lecture Video, Circle of 5th’s:

Concept Check

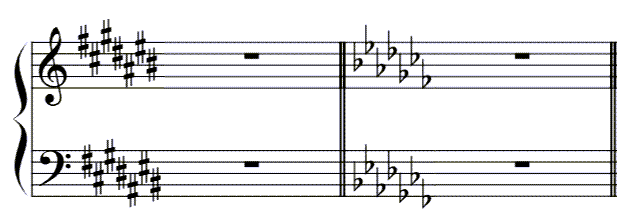

Example 4-4: Practice writing the key signatures for the following major keys: D, Eb, B, Cb. Use the full key signature chart from above. You will notice a pattern that each clef and group of sharp or flat accidentals follow. After the first accidental, sharps go “down-up-down, etc.” and flats go “up-down-up, etc.”

Music in Different Keys

What difference does a “key” make? Since the major scales all follow the same pattern, they all sound very much alike. The same tune looks very different written in two different major keys, but will sound, relatively, the same. Here is a likely familiar melody written first in D major, then in Ab and G.

Look & Listen!

The music may look different, but the only difference when you listen is that one in Ab major sounds lower, and then in G major sounds slightly lower again. You might also notice that it takes 2-5 notes for the melody to sound “right” to your ear after it switches keys: this is your brain shifting to the new tonic pitch. Why bother with different keys at all? Most importantly, choosing a particular key is easier to sing or play in that key compared with another. There are subtle differences between the sound of a piece in one key or another, mostly because of differences in the timbre of various notes on the instruments or voices involved. Try singing a simple song starting on a lower pitch, and then again on a much higher pitch–notice how the quality of your voice changes.

“Key” Takeaway (pun intended)

Musicians often talk about pieces being “in” a key. This is their way of mentally collecting together all the materials that they will use in that piece: scales, chords, harmony, and melody. That’s right, it means a lot to them! Whether they are learning, memorizing, or improvising music, understanding scales and keys is very important to understanding how tonal music (pop, jazz, classical) works.

Minor Keys and Scales

Music that is in a minor key is sometimes described as sounding more solemn, sad, mysterious, or ominous than music that is in a major key.

Lecture Video, Minor Keys Introduction:

Minor scales sound different from major scales because they are based on a different pattern of intervals. Just as with major scales, starting the minor scale pattern on a different note will give you a different key signature – a different set of sharps or flats. Also note: the basic minor scale pattern is the same as the Aeolian mode from the earlier discussion.

Parallel Major and Minor Keys

Another way of “traveling” between Major and Minor keys is through a Parallel relationship. In this case, the tonal center (tonic pitch) of the keys/scales is the same. Consider the C major scale below–to create its parallel minor scale, lower the 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees, which would make Eb, Ab, and Bb:

Key Takeaways

Lecture Video: Parallel Minor:

Look & Listen!

The minor scale created in the prior examples creates a new key signature by changing 3, 6, and 7. With the new key signature to create the minor scale, it is called the natural minor scale. It’s a real nuisance, but the word “natural” here does not refer to the accidentals (or lack of accidentals). It means that the notes are “natural” to the key signature, as opposed to the Harmonic and Melodic minor scales – which we will get to later – and use accidentals in the scale in addition to the key signature (again, more later!).

Lecture Video, Natural minor and KS:

Concept Check

Example 4-5: For each note below, write a natural minor scale, one octave, ascending or descending.

A Minor, ascending ![]()

G Minor, descending ![]()

Bb Minor, ascending ![]()

Relative Minor and Major Keys

As with Major keys and scales, it is important to memorize the minor key signatures as well. Notice that in the Circle of 5th’s that each minor key (lower case, inside of the circle) shares a key signature with a major key (upper case, outside). A minor key is called the Relative Minor of the major key that has the same key signature (and vice versa, the major key is the Relative Major to the minor). Even though they have the same key signature, a minor key and its relative major sound very different (Look & Listen below). They have different tonal centers (tonic pitch), and each will feature melodies, harmonies, and chord progressions built around their respective tonal centers. It is easy to predict where the relative minor of a major key can be found. Notice that the pattern for minor scales overlaps the pattern for major scales. In other words, they are the same pattern, but starting in a different location in the scale (you might not have noticed this while we were building the parallel minor scale). The Relative Minor scale begins on the 6th scale degree of a Major scale; conversely, the Relative Major scale begins on the 3rd scale degree of the Minor scale. The Eb major and C minor scales start on different notes, but have the same key signature and the same pitches, making them related keys. The Eb and C pitches have been color coded, and the W & H step patterns have been marked to see the rotation of the pattern.

Look & Listen!

Here’s a chart to summarize how relative keys work with regard to the Tonic and the Key Signature.

Table comparing relative keys.

| Tonic | Key Signature | |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Keys | Different | Same |

Lecture Video: Relative Minor:

Concept Check

Example 4-6: What are the relative majors of the minor keys in Concept Check, Example 4-5?

Recall that the relative example we just looked at shows a scale in two different keys (tonal centers), and the effect is a higher or lower pitch, which can be 1) to make it easier for a singer to perform (range); 2) give a different “feel,” timbre, to the melody based on who (singer) or what instrument is performing it. Switching to a Parallel key creates this shift without changing the tonal center: C major and C minor share the same tonic pitch, so the melody will not sound higher or lower. Making this change to the Relative minor would create the dramatic “mode” shift—between major (originally called Ionian mode) and minor (originally called Aeolian mode) —and the tonal center change.

Tabel comparing Relative and Parallel Keys.

| Tonic | Key Signature | |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Keys | Different | Same |

| Parallel Keys | Same | Different |

Here is the ABC song demonstrating the concepts, first in D major, then in the parallel D minor, then back in D major, and finally in the relative minor, B minor.

Look & Listen!

Concept Check

Example 4-7: Recreate the Major scales from Example 4-3, Step 1) using a Key Signature, and then Step 2) create the parallel natural minor scale with added accidentals by the correct pitches.

Begin on F4, ascending ![]()

Begin on Ab4, ascending ![]()

Begin on A4, descending ![]()

Scale Degree Names and Functions

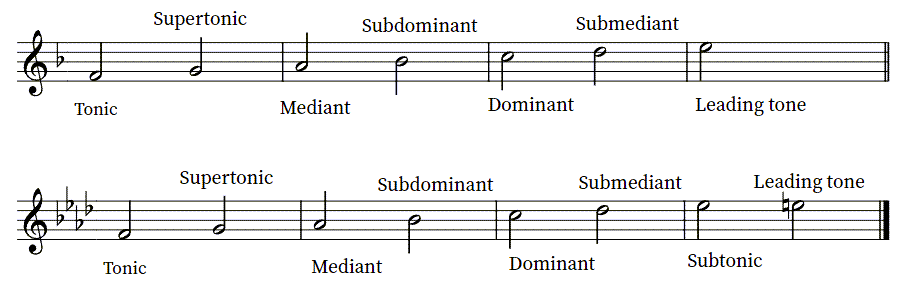

Musicians commonly refer to scale degrees by number and by name. These names have certain “functions” associated with the scale degree, and how it “acts” in a key. For example, the Leading Tone, the 7th scale degree, sounds like it needs to resolve (lead) to the first scale degree.

The names of the scale degrees: examples show F major and F minor – the only practical difference that minor has two 7th scale degree names for natural 7th and harmonic 7th.

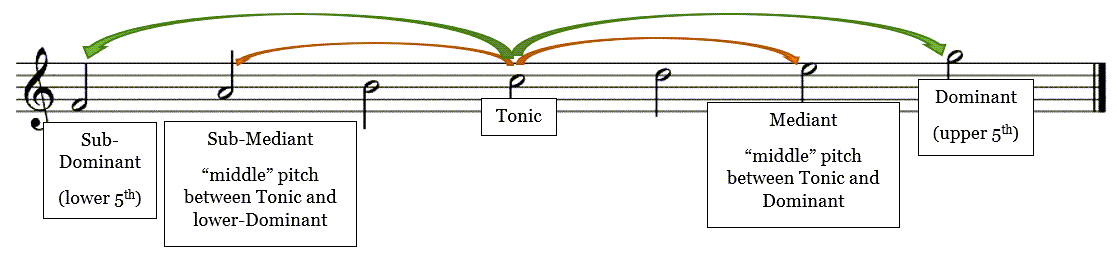

The Tonic is the center of the scale in importance and sound–it’s “home.” The interval of the 5th is also very important in Western history (as shown, in part, by the Circle of 5th’s). The Dominant scale degree is considered the second-most-important scale degree of a key in understanding the progression of musical melodies and harmonies. The symmetry of the scale was also important in history, and the Subdominant gets its name not from being one step below the Dominant, but by being the “under” dominant to the Tonic, as shown below: the symmetry of the 5th above and the 5th below.

Functional derivation of the degree names. The symmetry of scale degree names.

This also explains the Submediant name; the Mediant is the “middle” (Latin) of the 5th interval between Tonic and Dominant. Therefore, the 6th scale degree is the Sub–lower 3rd interval between Tonic and the Subdominant. The Supertonic is literally “above” (Latin super) and the lowered 7th scale degree is Subtonic. Leading tone, as discussed, has a strong tendency resolving towards the Tonic.

Lecture Video, Scale Degrees:

Lecture Video, Scale Functions: