Main Body

Rhythm: Music & Time

Rhythm is one of the more “natural” parts of music–it’s the easiest for people to grasp. We instinctively start to move to certain styles of music–being moved by the “beat.” Dancing is certainly one of the oldest and most ubiquitous activities and customs across cultures and history. While the feel of rhythm is universal, connecting it to notation is definitely not. As with pitch, there is a whole set of new symbols to familiarize yourself with: we’ll get the basics of those in this chapter.

Unlike some visual arts (like a painting or statue), experiencing music must occur through sequential time. True, looking at a painting occurs in time, but you don’t have to look at the parts of the painting in a particular order. How humans experience time is a fascinating study in psychology (also a specialized area of music psychology); how we experience time in listening to, or participating in, music is important to how it should be notated. Feel your pulse–your heart beat. It’s regular (for the most part) and slices up the passage of time: 60 beats per minute when resting, 140 beats per minute when running fast. Musicians also talk about beat, and they even determine how fast a song should be played by talking about “beats per minute.”

Beats

Because music is heard over a span of time, one of the most important ways that music is organized by thinking of music as comprised of short periods called beats – a sound that happens predictably, regularly. In most music, a lot happens right at the beginning of each beat. This makes the beat easy to hear and feel. When you clap your hands, tap your feet, or dance, you are “moving to the beat.” Your claps are sounding at the beginning of the beat, also called the articulation of the beat (note, pitch, sound). This is also called being “on the beat,” and it is analogous to when the conductor’s baton hits the bottom of its path and starts moving up again.

Concept Check

Example 3-1: Listen to excerpts A, B, C and D. Can you clap your hands, tap your feet, or otherwise move “to the beat”? Can you feel the 1-2-1-2 or 1-2-3-1-2-3 of the meter? Is there a piece in which it is easier or harder to feel the beat?

A

B

C

D

Concept Check

Building on the Beat: Meter

As the examples above illustrate, most music organizes into repetitive groupings of beats: 2s, 3s, 4s are common. We call this concept meter. You’ve heard of measuring in feet, yards, and meters – that’s exactly what the word meter refers to (more old Latin, the word “measure”), but now it’s measuring time. The meter of a piece of music is the arrangement of its rhythms in a repetitive pattern of strong and weak beats, as we heard above. Of course, this doesn’t mean that the rhythms, per se, are repetitive.

Some music does not even have a meter. Ancient music, such as Gregorian chants; new music, such as some experimental contemporary music, and various other World music, may not have a strong, repetitive pattern of beats. Other types of music, such as Indian music, may have very complex meters that can be difficult for the beginner to identify.

But most Western music, especially since the Baroque style period, has predictable, repetitive patterns of beats. This makes meter a very useful way to organize the music into measures, marked off by bar lines. These help the musicians reading the music to keep track of the rhythms.

Let’s clarify some terms before proceeding:

Table of Rhythm and Meter Terms and Definitions

| Pulse | Like the pulse in your body, pulse in music refers to any periodic (regularly recurring) sound. |

| Accent | Stressing one or more of these pulses. Typically, this is done by playing them louder, but can be stressed in other ways: agogic (length), range (a higher/lower note that stands out from surrounding pitches). It can be a regular accent (metrical) or irregular (syncopated–discussed later). |

| Grouping | Assigning a pattern to the accents that groups a particular number of pulses together. |

| Beat | The technical name for pulses when they have an accent pattern that groups them into a metrical pattern (meter). NOTE: This definition of beat is called Metrical Beat. This is how composers communicate their musical intention to performers through the use of a Time Signature, Tempo markings (the speed of beat value), and other notational means. Performance beat is how musicians interpret the notation in performance, which can have some flexibility. |

| Division | How the beat is divided, either into 2 or 3 (there can be other divisions, but they are beyond this course). |

| Subdivision | A further division of the division into 2. There can be other ways of subdividing, but they are beyond this course. |

| Levels of Beat | Beat, Division, Subdivision all refer to levels of beats within a meter. You can tap your foot, dance, conduct, etc. to any of these levels–that is the point of performance beat–how you feel the music. Technically, musicians generally need to agree on which level they are performing a piece of music. |

| Time Signature | The notated expression of a meter. This does not limit the performance beat interpretation; it makes it practical, though, for musicians to be able to interpret a composer’s intentions. Meter and Time Signature are often thought of on a practical level as synonymous, but it’s important to note that they are not, technically, the same. |

| Tempo | The speed of music. Musicians communicate this in talking about the speed of the beat. When you hear a musician giving a “count-off,” they are telling the other musicians the tempo. More precisely, in notation, there are two ways to specify a tempo. Metronome markings are absolute and specific, e.g., ¼ = 132 bpm (beats per minute). Other tempo markings are verbal descriptions that are more relative and subjective. Both types of markings usually appear above the staff, at the beginning of the piece, and then at any spot where the tempo changes. |

| Conducting | Beyond the scope of this course (take Music 5 if you’d like to learn how!), but has some related concepts that help illustrate meter. Conducting depends on a combination of the meter beat and the performance beat of the piece; conductors use different conducting patterns for the different meters. These patterns emphasize the differences between the stronger and weaker beats to help the performers keep track of where they are in the music. Regardless of what pattern the conductor is doing, the performers may interpret the pattern in a different way to help them understand a passage better. Conversely, a conductor may choose to conduct a time signature with a different pattern from the time signature in order to make it easier for the ensemble to perform. |

Even though the time signature is often called the “meter” of a piece, one can talk about the meter without worrying about the time signature or even being able to read music. This is how many singers, who don’t read music, are able to participate in choirs: they listen to others and follow the general contour of the written music; you can feel and perform a meter without knowing how to read/interpret the time signature (notation) of that same meter.

Lecture Video – Meter, Pulse, Groupings:

Lecture Video – Grouping, Accent, Conducting:

If you’re curious, here is a series on conducting basics by Leonard Slatkin: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL2_S0hFw3zDl47TtV7iYbu—XhiuSrkgaW We also cover conducting in Music 5.

Rhythmic Notation

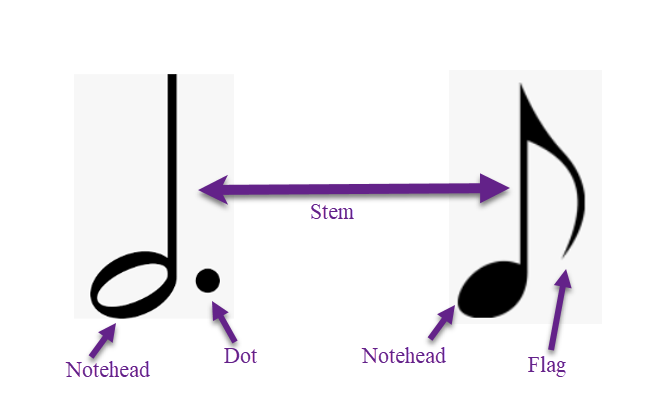

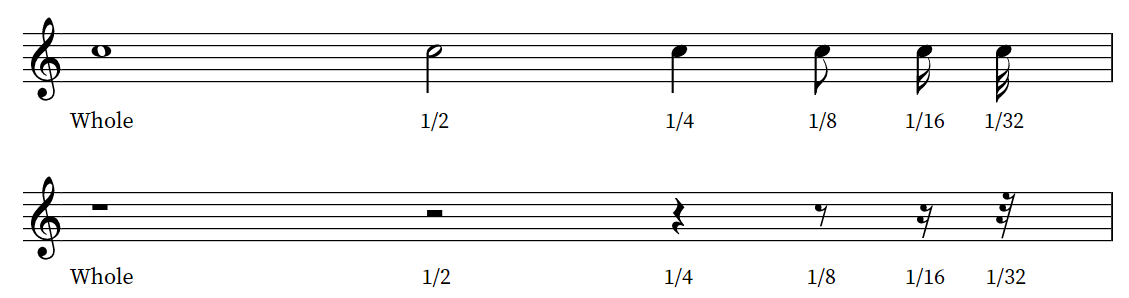

All of the parts of a written note affect how long it lasts. The circle portion, the notehead, does double duty: 1) pitch and 2) rhythmic value, depending on whether it is solid or hollow.

Since music has to occur in time, we need a way of communicating how long each pitch should last. The symbols above have “value” or length in time. The simplest-looking note, with no stems or flags, and an unfilled notehead, is a whole note. All other note values are defined by how long they last compared to a whole note. All other note values are distinguished by the following variables:

- Filled or empty notehead

- Stem or no stem (the whole note is the only one without a stem)

- Flag(s) or no flag

The most common note values.

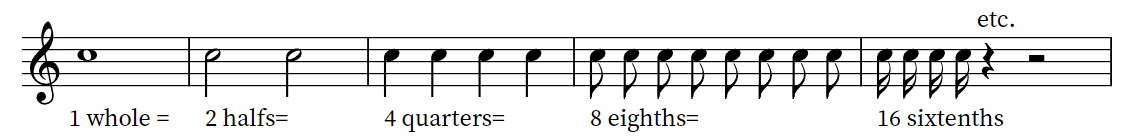

Note values are proportional. A note that lasts half as long as a whole note is a 1/2 note (the only other note with an empty notehead). A note that lasts a quarter as long as a whole note is a 1/4 note. The pattern continues with 1/8 notes, 1/16 notes, 1/32 notes, 1/64 notes, and so on, each type of note being half the length of the previous type (we won’t go beyond the 1/16th note in this course). In common Western music styles, there are no specific note symbols for 1/3 notes, 1/6 notes, 1/10 notes, etc., but there are ways to create unique values.[1]

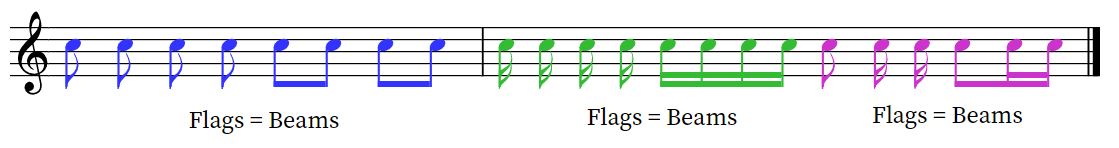

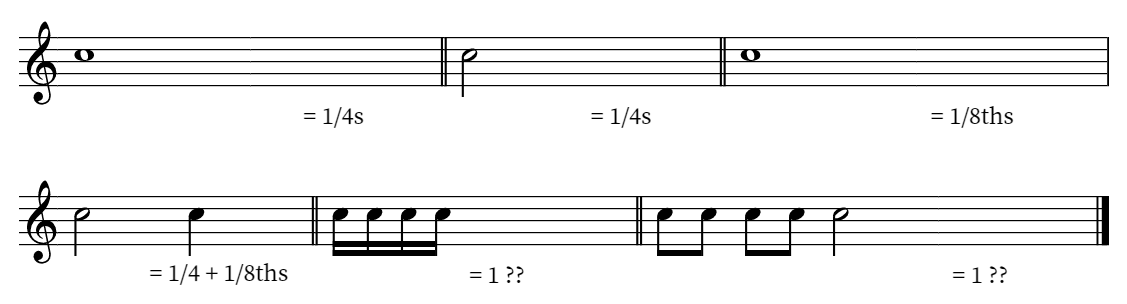

Note lengths work just like fractions in arithmetic: two 1/2 notes or four 1/4 notes last the same amount of time as one whole note. Flags are often replaced by beams that connect the notes into easy-to-read groups.

Notice that some of the eighth notes above don’t have flags; instead they have a beam connecting them to another eighth note. If flagged notes are next to each other, their flags can be replaced by the same number of beams that connect the notes into easy-to-read groups. How these groups work is covered in Chapter 3B.

Beams

The notes connected with beams are easier to read quickly than the flagged notes. Notice that each note has the same number of beams as it would have flags, even if it is connected to a different type of note. The notes are connected so that each beamed group gets one beat. This makes the notes easier to read quickly.

Lecture Video: Note Values, Stems, Beams:

Concept Check

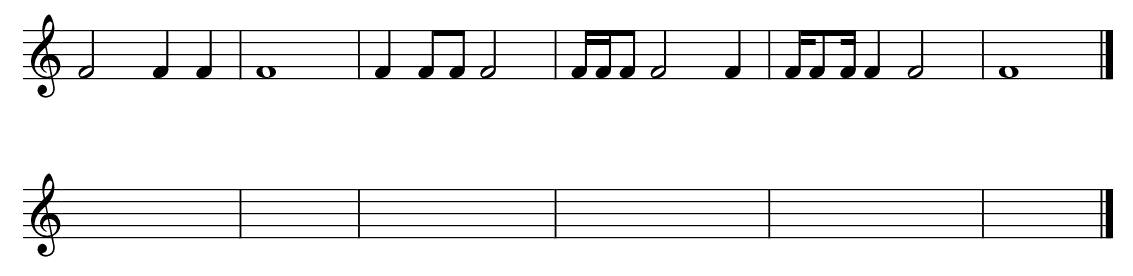

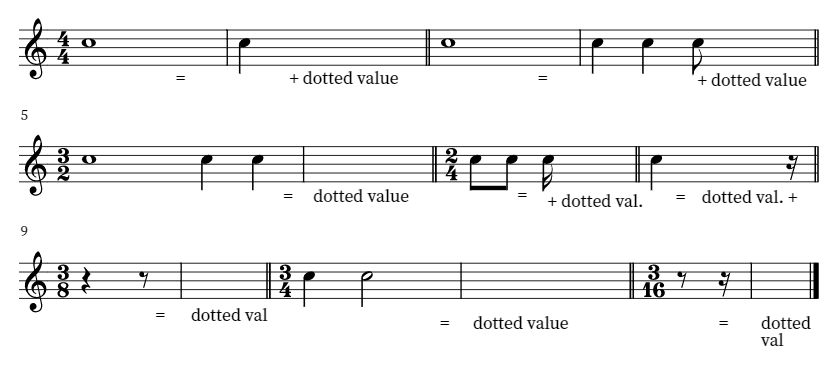

Example 3-3: Print and draw the missing notes and fill in the blanks to make each side the same duration (length of time). Draw notation

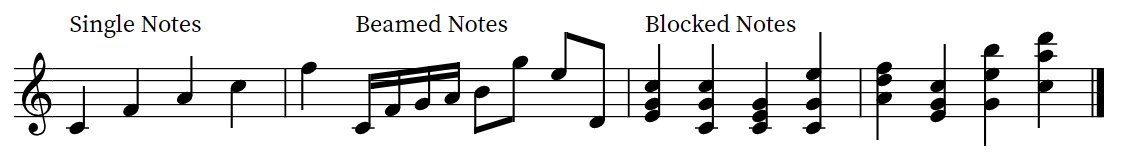

Basic Note Stem Rules

- Single Notes—Notes below the middle line of the staff should be stem-up. Notes on or above the middle line should be stem-down.

- Notes sharing stem (block chords)—Generally, the stem direction will be the direction for the note that is farthest away from the middle line of the staff.

Keep stems and beams in or near the staff, but also use stem direction to clarify rhythms and parts when necessary.

Lecture Video – Stems:

Measures and Barlines

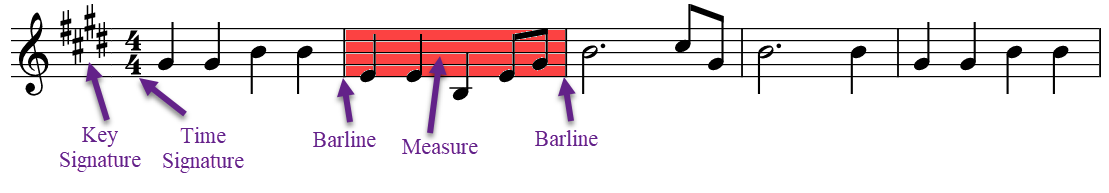

Let’s put together a number of elements that we’ve been discussing in more detail here, as they are used in a musical score, visualized below.

Vertical barlines divide the staff into short sections called measures or bars; these terms are often used interchangeably by musicians, but they are technically not the same. Barlines are the vertical line marking off a measure. A double barline, either heavy or light, is used to mark the ends of larger sections of music, including the very end of a piece, which is marked by a heavy double bar.

Important: Accidentals altering a pitch last only until 1) another accidental changes that same pitch; 2) more commonly, the barline cancels it out. Therefore, most accidentals usually only last for one measure; this is different from the Key Signature (more detail in the Scales chapter), which lasts for the entire piece of music (or until it changes in the middle)!

The most common elements on the staff, always read left to right. The space between each barline is a “measure.”

Duration: Rest Length

A rest stands for silence in music. For each kind of note, there is an equivalent written rest symbol.

The most common note values and their corresponding rest symbols.

The whole and half rests should be written on those specific lines: whole rest hanging on the bottom of the 4th line; half rest sitting on top of the 3rd line.

Concept Check

Example 3-4: For each note on the first line, write a rest of the same length on the second line. The first measure is done for you.

Rests can specify silence in a particular part only as well. On a staff with multiple parts, a rest must be used as a placeholder for one of the parts, even if a single person is playing both parts. When the rhythms are complex, this is necessary to make the rhythm in each part clear.

LOOK & LISTEN: When multiple simultaneous rhythms are written on the same staff, rests may be used to clarify individual rhythms, even if another rhythm contains notes at that point.

Time Signatures

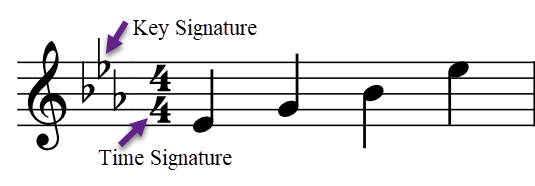

The time signature appears at the beginning of a piece of music, right after the key signature (more on this in Chapter 4). Unlike the key signature, which is on every staff, the time signature will not appear again in the music unless the meter changes. The meter of a piece of music is how its basic rhythm is grouped (more in Chapter 3B!); the time signature is the symbol that tells you the meter of the piece and how (with what type of notes) it is written.

The time signature appears at the beginning of the piece of music, right after the clef symbol and key signature.

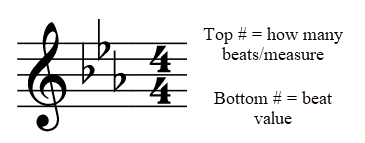

The time signature tells you two things: 1) how many beats there are in each measure, and 2) what type of note holds the beat value. Time signatures contain two numbers. The top number tells you how many beats there are in a measure. The bottom number tells you what kind of note holds the beat value.

This time signature means that there are four quarter notes (or any combination of notes or rests that equals four quarter notes) in every measure. A piece with this time signature would be “in fourfour time” or just “in four-four”.

In “four-four” time, there are four beats in a measure and a quarter note is the beat. Any combination of notes or rets that equals four quarters can be used to fill up a measure.

Lecture Video: Time Signatures:

Dotted Notes

What if you want a note (or rest) length that isn’t half of another note (or rest) length? For instance, what if you want to fill an entire measure of three-four meter? A ½ note is too little, a whole note is too much. This is when we use a dot notation.

A dotted note is one-and-a-half times the length of the same note without the dot. In other words, the note keeps its original length and adds another half of that original length because of the dot. A dotted half note, for example, would last as long as a half note plus a quarter note, or three-quarters of a whole note.

Another–and better method–is to realize that every dotted note is equal to three of the next smaller value (i.e., the value of the dot).

Method A is adding the half value—the dot—to the main note. Method B shows the three next-smaller note values that any dotted not is equal to.

Concept Check

Example 3-5: Make groups of equal length on each side, by putting a dotted note or rest in the box.

A note may have more than one dot. Each dot adds half the length that the dot before it added. For example, the first dot after a half note adds a quarter note length; the second dot would add an eighth note length. Double-dotted notes are fairly rare, so we won’t deal with them further in this class.

When a note has more than one dot, each dot is worth half of the dot before it.

Lecture Video – More on Time Signatures, Beat, Division plus Dotted Notes (c. 3:15):

Alternate Time Signatures

A few time signatures don’t have to be written as numbers. Four-four time is used so much that it is often called common time, written as a bold “C”. [The “C” abbreviation was not originally a letter C, but half of a circle, that was derived from an older notation system.] When both fours are “cut” in half to twos, you have cut time, written as a “C” cut by a vertical slash. We will not be covering cut time or 2/2 time in this class.

Alternate notation for 4-4 and 2-2 time signatures.