Appendix

The appendix is currently a catch-all for sections moved out of the main text in the latest edit (1/2024).

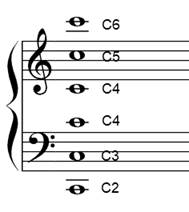

Using Different Clefs

Music is easier to read and write if most of the notes fall on the staff and few ledger lines have to be used.

Look & Listen!

This score show the same notes written in treble and in bass clef. The staff with fewer ledger lines is much easier to read and write. Notice that both lines of music sound the same (high/low).

Voices and instruments with higher ranges usually learn to read treble clef, while voices and instruments with lower ranges usually learn to read bass clef. Instruments with ranges that do not fall comfortably into either bass or treble clef may use a C clef (not studied in this class).

Diatonic and Chromatic half steps

- C to C# is a half step; C to Db is also a half step. They are enharmonic versions of the same half step.

- F# to G# is a whole step; Gb to Ab is also a whole step; Gb to G# is also a whole step. They are all enharmonic versions of the same whole step.

- Rule: if the pitch classes are the same (both C or both G), then it is a chromatic half step; if the pitch classes are different, then it is a diatonic half step.

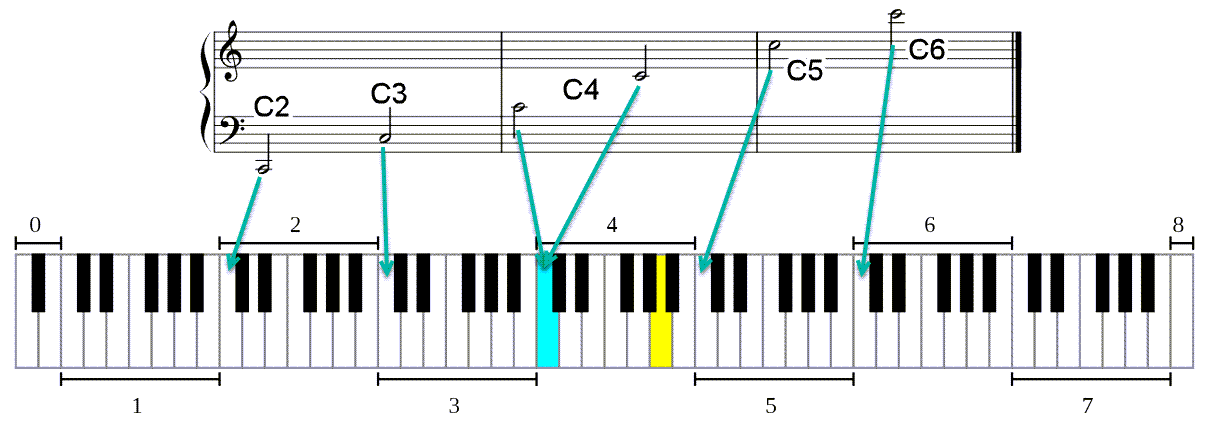

Numbering Octaves

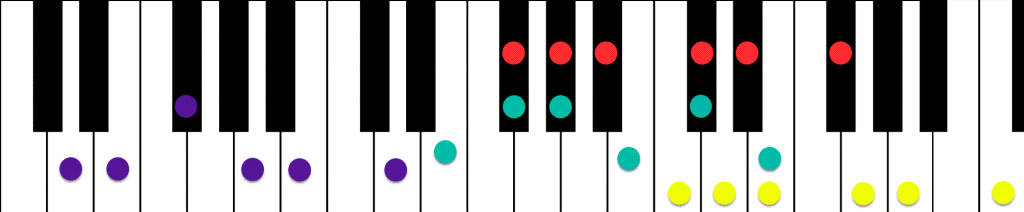

Musicians often need to know precisely how high or low in the range a pitch is, so there is a labeling system that is associated with the piano. The basic idea is that there are 8 “C” pitches on the piano, so they mark off the possible number of octaves. The piano begins with three pitches below the lowest C, so they are referred to as the zero (0) octave pitches. All other pitches are labeled within the C through B range for each octave, as below.

The octave labeling system on the grand staff and in relation to the piano keyboard, showing the most practicaly used range of pithces. Turqoise key is middle C; yellow key is A4, also known as “A 440” (440 Hertz) – the standard tuning pitch in the western system.

A simpler version of the octave boundaries.

Lecture Video: Clefs, the Keyboard, Octaves:

Lecture Video: Ledger Lines, More on Octaves:

Lecture Video: Ledger Lines, the Keyboard, and the Grand Staff:

Concept Check

Example 2-2:Write the name and octave of each note below the note on each staff.

Enharmonic Intervals

The diminished fifth and augmented fourth sound the same on the keyboard. Why? Both are six half-steps, or three whole tones, so another term for this interval is a tritone. In Western Music, this unique interval, which cannot be spelled as a major, minor, or perfect interval, is considered unusually dissonant and unstable (tending to want to resolve to another interval). It’s also unique because it splits the octave exactly in half (6/12 HS). The name, tritone, comes from when it is spelled an Augmented 4th (see the Pitch Class Interval Quality chart above: F-B, broken down as three whole steps = F-G, G-A, A-B = 3 (whole) tones. In a much earlier system, the tetrachord (4th scale), played an important role in music theory, and “tone” was the common term for what we call a whole step.

You have probably noticed by now that the tritone is not the only interval that can be notated in more than one way. In fact, because of enharmonic spellings, the interval for any two pitches can be written in various ways. A major third could be written as a diminished fourth, for example, or a minor second as an augmented first (practically, though, enharmonic intervals are not that common for beginners). Always classify the interval as it is written; the composer had a reason for writing it that way. That reason sometimes has to do with subtle differences in the way different written notes will be interpreted by performers, but it is mostly a matter of placing the notes correctly in the context of the key (Ch. 4), the chord (Ch. 6), and the harmony (Ch. 8).

Look & Listen!

Any interval can be written in a variety of ways using enharmonic spelling. Play the example above to hear how each pair sounds identical, although spelled differently–explanation below.

- A) In Ch. 2, we called these simply half steps, but distinguish between diatonic (eg., G-Ab) and chromatic (eg., G-G#) spellings. Here, you can see that with the interval number category added, we have to spell them as a 2nd (G-Ab) and as 1st (G-G#),to distinguish the pitch class difference.

- Examples B through D show further examples that are equivalent in sound, but are enharmonic in spelling.

Simple and Compound Intervals

Interval numbers are also classified by two larger categories: Simple intervals are one octave or smaller.

Look & Listen!

Compound intervals are larger than an octave. You simply keep counting, as you can see from the examples below. From E up to the F an octave higher, E to E would be 8, so F is 9, etc. To convert a compound interval to simple or vice versa, simply add or subtract seven–not eight. If you add/subtract 8, then you are double-counting the octave pitch in your calculation. Prove this to yourself by counting the examples below, and then subtracting 7 from the compound interval. If you move the higher note down an octave, it will match the simple interval.

Look & Listen!

Pitch Class Interval Method

This method uses the white keys on the piano, or the generic pitch-class intervals, i.e., no accidentals to start with.

Look & Listen!

Resource

Hey! You are going to want to print these charts, like right now. Exactly, stop everything, download and print this document asap: WK Intervals Method Charts

At the very least, have it available in another window to refer to.

Press the play button in the Noteflight version and listen through the entire chart.

Key points for the Pitch Class Interval Chart:

- Number Groups:

- 2nds and 7ths will sound dissonant. Remember, this isn’t a negative judgment–it’s just an acoustic observation that will help classify various musical sounds aurally–and make it easier to hear the difference.

- 3rds and 6ths will sound consonant.

- 4ths and 5ths will sound consonant, but kind of “different”. We don’t use these intervals by themselves much in the past several hundred years (seriously!), so they sound a bit odd or old-fashioned to our ears. I like to describe them as somewhat “hollow” sounding (that will make more sense when we study chords).

- Primes (1) and Octaves (8) are not shown, because they are easy–all of them are Perfect when they have no accidentals, or matched accidentals.

- Blue Intervals:

- You might notice that within each number group, the blue-colored intervals sound different from the rest–they have a different quality (one half step different) from the others in the group.

- Don’t worry if you don’t hear the differences! You will notice it most easily inside the 4th and 5th groups–the F-B and B-F pairs. It takes musicians quite a bit of time and practice to hear these interval differences (not our primary goal in this class). The goal here is to point out the distinction.

- Qualities:

- The qualities for each number group, and the blue distinctions, are listed above each group. Refer to the Category chart above to remember the quality name and difference in half steps.

- Bl. = “blue”; m = minor, M = major; Aug. = augmented (a superscript + sign is also used for Aug.); Dim. = diminished (a superscript o sign is also used for Dim.)

The power of this chart is:

- Understand that the blue intervals–their quality difference–are relatively few within each group. This makes them easier to memorize.

- Realize that for each number group, the remaining intervals are all the same quality. You now have a starting point for a given interval number and quality, and then you modify it using the Category/Quality Chart above.

Shortcuts to remember:

- MAP (Matched Accidental Principal): the starting quality of any interval number remains the same when modified by the same accidental, i.e., if D up to B is a Major 6th, then Db up to Bb is also a M6, because the distance between has not changed.

- 2nds—E-F and B-C are the only HS on the white keys, and they are the only HS in the 2nds!

- 3rds—the ones starting on C, F, G are Major, all others minor.

- 4ths—all are Perfect, except one pair of notes, F and B.

- 5ths—all are Perfect, except one pair of notes, B and F.

- 6ths—the ones starting on E, A, B are minor.

- 7ths—the exact opposite of the 2nd’s—all minor, except the F-E and C-B are Major. Notice that F-E / C-B are the same pitch pairs as the 2nds!

Lecture Video: Pitchclass Interval Method:

Identifying an interval.

This interval is a 7th, so I find C to B (natural!) on the 7th part of the chart and see that it is Major, and then decrease the interval quality from Major to minor, by using Figure 5-5, on p. 3, to account for the HS change of the flat. Answer: m7.

Here’s another example, but now building the interval.

Building an interval.

How to build a Diminished 5th, built on an Ab:

a.–We are given Ab.

b.–On the chart, A to E is P5, but so is Ab-Eb (MAP, same accidentals).

c.–Lower the Eb to Ebb for a d5.

Pitch Class Chords Method

Becoming proficient with chords takes time and practice, but there is a way to make that practice more efficient. Musicians who use chords frequently have multiple ways of thinking about them, but that isn’t always practical for a general education student.

The best way to start is to stick with one method, which for this course is the pitch class method.

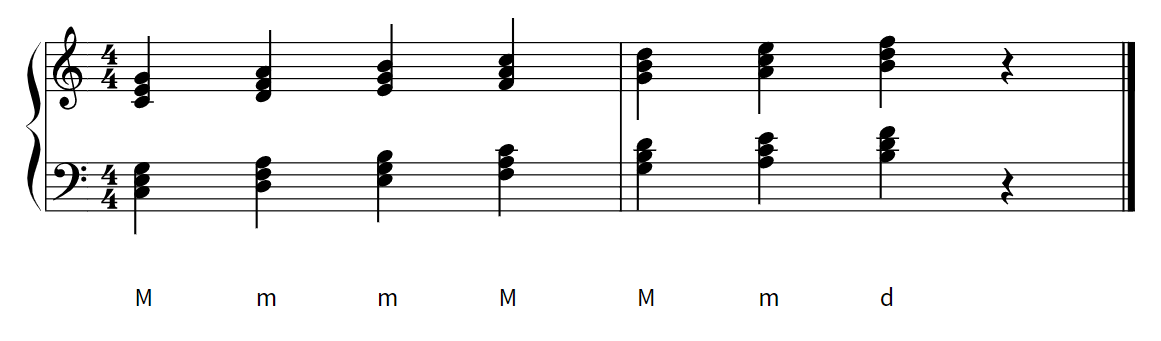

First, memorize the triad qualities of the pitches of the piano white keys only. Do this picturing them on the piano and on the staff, as below.

The qualities of the white key triads:

- All Major and Minor Triads have a P5 from Root to 5th

- The bottom third, which gives them their name, is the only difference.

- C, F, G are the only white-key Major triads (bottom 3rd is Major).

- The only diminished chord–on pitch B–has a diminished 5, which gives it its name; it also has a m3 on bottom.

Look & Listen!

Second, using the MAP technique, learn to convert any white-key Triad to a chromatic version (and vice versa). This works because if you alter all the notes of a triad in the same way, then the relative intervals have not changed, so the quality has not changed.

Look & Listen! Chromatic altering of a complete triad. Each example maintains the same quality.

Third, memorize the four common ways to alter a Triad quality as follows.

Look & Listen!

Application

These are only examples; the method works on every root position triad. Once you have established the first quality–on any pitch–then you can create the second quality (and vice versa).

- Major to minor by lowering the 3rd; minor to major by raising the 3rd.

- Major to augmented by raising the 5th; augmented to major by lowering the 5th.

- Minor to diminished by lowering the 5th; diminished to minor by raising the 5th.

- Diminished to major by lowering the root; major to diminished by raising the root.

Remember that raising and lowering are relative to the context of the key signature or any accidentals, but these always hold true:

- flat raises to natural; natural lowers to flat

- natural raises to sharp; sharp lowers to natural

- more advanced:

- sharp raises to double sharp; double sharp lowers to single sharp

- flat lowers to double flat; double flat raises to single flat

To find any triad starting on an accidental, take the closet white-key chord and convert it chromatically. If it is the same quality, then you’re done; if it is a different quality, then use the quality conversion method to create the right quality as needed (major to minor or vice versa, minor to diminished, etc).

You will only need the chromatic conversion technique for the 5 black keys of the piano. And any triad on Bb can just use the Bo chord and convert from thereby sliding the root down a ½ step. After practice, you’ll realize you can start to manipulate any chord in a variety of ways, as you get more familiar with certain chords that are used repeatedly.

Lecture Video: Pitchclass Method, Pt. 1:

Lecture Video: Pitchclass Method, Pt. 2:

Transposition—Changing Keys

Changing the key of a piece of music is called transposing the music. When an entire piece is written in a new key, it is called transposition; when it occurs in the middle of a piece, then it is called modulation, or “key change” (covered in later courses). Music in a major key can be transposed to any other major key (Happy Birthday played in D, Eb, A, etc.; music in a minor key can be transposed to any other minor key.

Word Watch

Changing a piece from minor to major or vice—versa is called “mode change,” and requires more changes than simple transposition, and is beyond this course.

A piece will also sound higher or lower once it is transposed (depending on how large an interval it is transposed by). Transposing a piece in D major to Eb major would only be a minor 2nd shift; transposing from D major to Bb would be more dramatic, depending on whether you moved the music up a minor 6th, or down a major 3rd (see how all these concepts come back?). There are some ways to avoid having to do the transposition yourself (computers and talented friends), but learning to transpose can be very useful (sometimes necessary) for performers, composers, and arrangers.

Why Transpose?

Here are the most common situations that may require you to change the key of a piece of music:

- To put it in the right key for your vocalists. If your singer or singers are struggling with notes that are too high or low, changing the key to put the music in their range will result in a much better performance.

- Instrumentalists may also find that a piece is easier to play if it is in a different key. Players of both bowed and plucked strings generally find fingerings and tuning to be easier in sharp keys, while woodwind and brass players often find flat keys more comfortable and in tune.

- Instrumentalists with transposing instruments will usually need any part they play to be properly transposed before they can play it. Clarinet, French horn, saxophone, trumpet, and cornet are the most common transposing instruments.

Avoiding Transposition

In some situations, you can avoid transposition, or at least avoid doing the work yourself. Some stringed instruments—guitar for example—can use a capo to play in higher keys.

Capo in Action

Here you can see Olivia Rodrigo (and other members of her band) using a capo. This isn’t “just a cheat” for transposition, as there are couple reasons why to use one: 1) yes, it does make it easier to transpose. If you learned a song in one key, but then need to change it, you can play the same chords (finger patterns); 2) Using the capo moves your hand up the strings, which changes the timbre – sound quality – of the guitar, so sometimes a guitarist just likes to use the capo for that reason. Of course, this will also change the singer’s timbre! It’s not really clear for which reason they are using capos here.

Advanced Application: Adding a capo only raises the pitch of a guitar, because you are shortening the strings. If a guitarist is accompanying a singer who needed a lower key, they would need to use interval inversion. For example, if the song is in G, and the singer needed it lowered a m3 to E, the guitar would capo up a M6. The singer would then sing an octave lower than the guitar. This isn’t always a practical solution, because as just noted, the more you capo a guitar, the more dramatically its timbre changes.

A good electronic keyboard will transpose for you. If your music is already stored as a computer file, there are programs that will transpose it for you and display and print it in the new key (like Noteflight!). Even with all of these “tricks,” it’s still good to understand how transposition works.

NOTE: If you think about the role of leadsheet symbols, transposing music based on the chords is just a matter of transposing the leadsheet symbols for the accompaniment part. If you play a chordal instrument (guitar or keyboard), you may not need to write down the transposed music of the melody, if you can learn to do it “in your head,” as many musicians do.

How to Transpose Music

There are four steps to transposition:

- Choose your transposition.

- Use the correct key signature.

- Move all the notes by the correct interval.

- Take care with your accidentals.

Step 1: Choose Your Transposition

In many ways, this is the most important step, and the least straightforward. The transposition you choose will depend on why you are transposing. If you already know what transposition you need, you can go to step two.

If not, please look at the relevant questions below first:

- Are you rewriting the music for a transposing instrument?

- Are you looking for a key that is in the range of your vocalist?

- Are you looking for a key that is more playable on your instrument?

Step 2: Write the New Key Signature

If you have chosen the transposition because you want a particular key, then you should already know what key signature to use. If you have chosen the transposition because you wanted a particular interval (say, a whole step lower or a perfect fifth higher), then the key changes by the same interval.

Transposition and Key Signatures

When changing keys, it is good to know not only the new key signature, but also the interval change between the two keys. Knowing this interval is especially important when changing the notes of an individual melody.

- C to D, M2 up

- C to Ab, M3 down (or m6 up)

- F to Bb, P4 up (or P5 down)

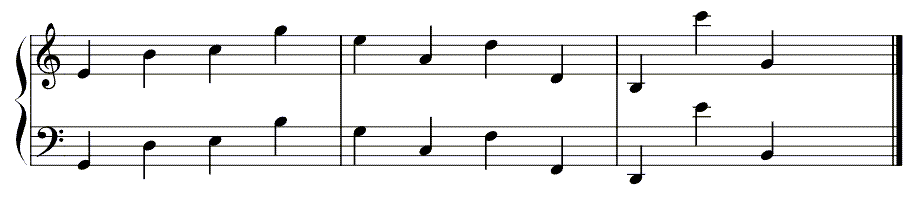

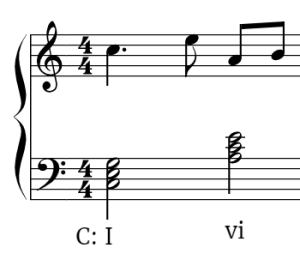

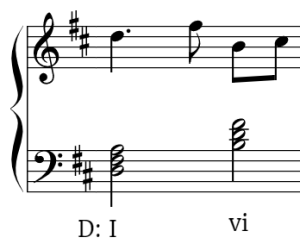

Look & Listen!

Step 3: Transpose the Notes

Now rewrite the music, changing all the notes by the correct interval. You can do this for all the notes in the key signature simply by counting lines and spaces. As long as your key signature is correct, you do not have to worry about whether an interval is major, minor, or perfect–the key signature takes care of that.

For diatonic transpositions–no accidentals in the music–then the key signature takes care of all changes, after the overall interval shift has been done. These are from the Noteflight example above.

Moving from C to D moves all notes up a M2. From C to Ab, down a M3.

Advance Proficiency

Once a musician knows their keys, scales, intervals, and chords proficiently, then transposition becomes simpler. Rather than thinking about each note changing by an interval, the musician can think about the chords and the melody in the new key, and based on a memorized “feel” of the scales and chords, transposes very quickly. For some musicians who do this a lot, they can do it on the fly while the music is being played.

Step 4: Be Careful with Accidentals

Most notes can simply be moved the correct interval number. Whether the interval is minor, major, or perfect will take care of itself if the correct key signature has been chosen. But some care must be taken to correctly transpose accidentals. Put the note on the line or space where it would fall if it were not an accidental, and then either lower or raise it from your new key signature.

For example, an accidental B natural in the key of E flat major has been raised a half step from the note in the key (which is B flat). In transposing down to the key of D major, you need to raise the A natural in the key up a half step, to A sharp. If this is confusing, keep in mind that the interval between the old and new (transposed) notes (B natural and A sharp) must be one half step, just as it is for the notes in the key.

NOTE: If you need to raise a note which is already sharp in the key, or lower a note that is already flat, use double sharps or double flats.

Check any accidentals. All chromatic alterations should match the same halfstep shift.

All notes shifted up M2 to D major scale. Notes that are chromatically altered need to match the original halfstep shift. The green notes are enharmonically spelled to be easier to read for the performer, as they use the more common white key spelling: C nat could have been ascending chromatic as B#; F natural could have used descending chromatic Fb. In both cases the given spelling is more common and easier to read.

All notes shifted down from C a M3 to Ab.

Flats don’t necessarily transpose as flats, or sharps as sharps. For example, if the accidental originally raised the note one halfstep out of the key, by turning a flat note into a natural, the new accidental may raise the note one halfstep out of the key by turning a natural into a sharp.

The Pentatonic Scale

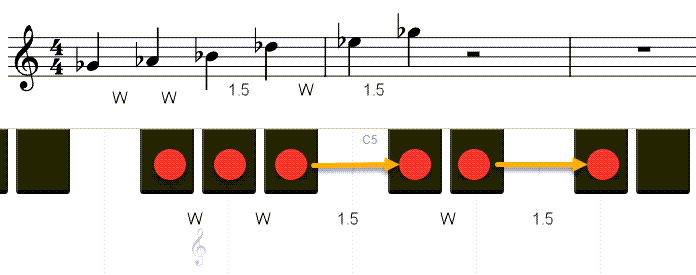

Let’s take what we’ve learned so far and apply it to our first scale–-the pentatonic scale—so named because it contains five distinct pitches (scales repeat the first pitch at the octave). All scales are a collection of pitches that follow a specific interval pattern, and the standard way of “spelling” them out is between an octave: starting on a pitch, following the interval pattern, and then ending on the same pitch again. Using our intervals from before, here is the pattern of the Major Pentatonic Scale (we’ll explain “major” soon):

W W 1.5 W 1.5

You can find this on the piano using only black keys, starting with the Gb (red dots), below:

Examples of the Major Pentatonic scale.

| C Major Pentatonic Scale | Yellow | C D E G A C |

| D Major Pentatonic Scale | Purple | D E F# A B D |

| E Major Pentatonic Scale | Green | E F# G# B C# E |

Play through these on a keyboard (right-click to open a separate window): https://www.musicca.com/piano

Another important point is that you can not (or should not) use just any enharmonic spelling of a pitch in this scale—they should all “match” accidental types for the pitches that need an accidental, i.e., all flats or all sharps. In the scale above, we would call that a Gb pentatonic scale (you could also spell the entire thing as an F# scale). For example:

Enharmonic spelling example of the pentatonic scale.

Gb Pentatonic: Gb Ab Bb Db Eb Gb

F# Pentatonic: F# G# A# C# D# F#

These are played on the piano using the same keys–enharmonically. It would not be correct to spell this scale with the pitch names mixed up:

You need to maintain the same accidental types in a pentatonic scale.

Musicians would find that pretty confusing (irritating, actually), because they have specific expectations about how certain scales work.

This concept is referred to as diatonic versus chromatic spelling. Simply put (there’s more history to it), diatonic means using matching accidentals (called staying “in the key”—more on that later, when we study keys), and chromatic means that you can use enharmonic variants.

Another application of this is how one spells a halfstep—chromatically or diatonically? A chromatic halfstep uses the same pitch-class name—C and C#, and a diatonic halfstep would use a different pitch-class name—C and Db. Therefore, when spelling the Major Pentatonic scale, if you ever use the same pitch class (two of the same letter name), then you’ve made a mistake! Notice in the incorrect example above that there are two A’s.

The major pentatonic scale is the basis of hundreds of songs, so it is very practical to know about. Let’s listen and look at an example that uses the D Major Pentatonic scale. Don’t worry about the “notation” symbols – we’ll get to those in Chapter 2. Just look at the basic contour (shape, flow) of the symbols moving up and down and you listen.

Look & Listen!

There’s a good chance you’ll recognize this as the very old song folk and gospel song, Amazing Grace. Here’s a list of popular songs that use this scale (https://www.guitarmusictheory.com/major-pentatonic-scale-guitar-songs/).

Enjoy this Bobby McFerrin video where he gives a fun demonstration of the Pentatonic Scale (3:03):

Sing along with this! Also, notice the “steps” and “skips” he puts in that match how you learned to spell the scale.

How does he do that?

- He is using Db Major Pentatonic. First he gives them Db, then Eb, repeats these, then the audience follows him intuitively to F (that’s the “aha” moment when everyone laughs). Then he separately gives them Bb, then they follow him down to Ab, then skips down to F, then all the way up to Db as tonic (the name of the 1st pitch of a scale).

- This works because he begins with the tonic of the Major Pentatonic, and then takes the audience up by WS, which is relatively easy, and mimics 1-3 of this scale.

- After this, he takes them down to Bb – but he has to give it to them. Why? This is the first interval shift, and is one of the 1.5’s in the scale. Once he’s done this, the crowd now “knows” the entire scale and he can go through multiple tunes, even descanting, as he does.

- He does this to show that it’s common to many cultures around the world. In some senses it is, but it’s a little bit of a trick. As I just explained, he had to give them a couple pitches to make the whole thing work, which they would not have gotten on their own. BUT, it’s still a fun demonstration, and partly does shows his point.

The Major Pentatonic Scale on the Staff

Let’s take the major pentatonic scale from Chapter 1 on the keyboard, and now place it on the staff, starting with the Gb version of the scale:

Pattern for the Major Pentatonic scale on Gb. NOTE: The first pitch of the scale, which gives it its name, is called the “tonic” pitch.

Look & Listen!

The Chromatic Scale

Rather than using a combination of hlaf and whole steps, the chromatic scale only uses half steps. It plays all the notes on both the black and white keys of a piano. It also plays all the notes easily available on most Western instruments. (A few instruments, like trombone and violin, can play pitches that aren’t in the chromatic scale, but even they usually don’t.) Since there are many enharmonic choices in a chromatic scale, musicians have some expectations about how they are spelled; see the appendix for clarification. We will only use{{{{{{{{

1) ascending chromatic scales and passages in music typically use natural and sharp notes and descending use natural and flat notes. 2) When there is a choice between the B-C, E-F enharmonic half steps, choose the natural version (i.e., if possible, avoid E# for F, B# for C, Fb for E, Cb for B). 3) For a scale or passage that starts on a flat note, use flats and naturals for the ascending as well. These are basic guidelines that favor making things consistent and easier for the performer to read; composers make other choices based on context.

Look & Listen!

You can also experiment with a Chromatic Scale using the Google Music Lab here: https://musiclab.chromeexperiments.com/Song-Maker Under the settings, select the Chromatic Scale.