Main Body

The Staff

Adam Neely on Notation (video)

People were talking long before they invented writing. People were also making music long before anyone wrote it down. Some musicians still play “by ear” (without written music), and some music traditions rely more on improvisation and “by ear” learning. But written music is very useful, for many of the same reasons that written words are useful. Music is easier to study and share if it is written down. Most of Western classical music specializes in relatively long, complex pieces for large groups of musicians singing or playing parts exactly as a composer intended. Without written music, this would be impossible. Many different types of music notation have been invented, and some, such as tablature, are still in use. By far the most widespread way to write music, however, is on a staff.

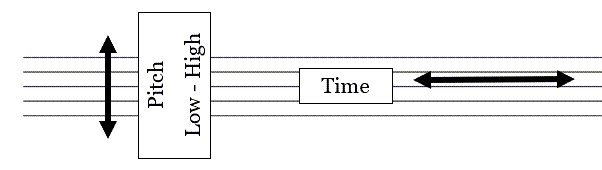

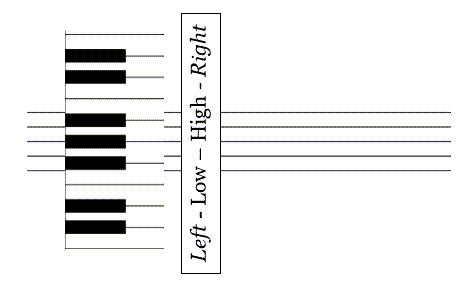

The staff acts similar to an X-Y coordinate graph from algebra class, only here the Y axis, vertical, is pitch and the X axis, horizontal, is time (rhythm).

The five lines of the staff act somewhat like a coordinate grid, with pitch located on the vertical axis and time moving left to right for rhythm (the time “grid” will be segmented into measures, in more detail, in the Rhythm chapters).

The staff (plural staves) is written as five horizontal parallel lines. How many lines are in a staff is not standard at 5, but in earlier eras was fewer, and developed gradually. Today, a common variant is the single-line staff, which is only for rhythm instruments.

The Staff and the Piano

Think of the staff as another way of dividing up musical space. Notes of the music are placed on these lines or in a space in between lines. The top of the staff represents relatively higher pitches, and the bottom of the staff, lower pitches. If you picture the piano keyboard turned vertically, with the righthand side turned up, that is essentially what the staff is representing.

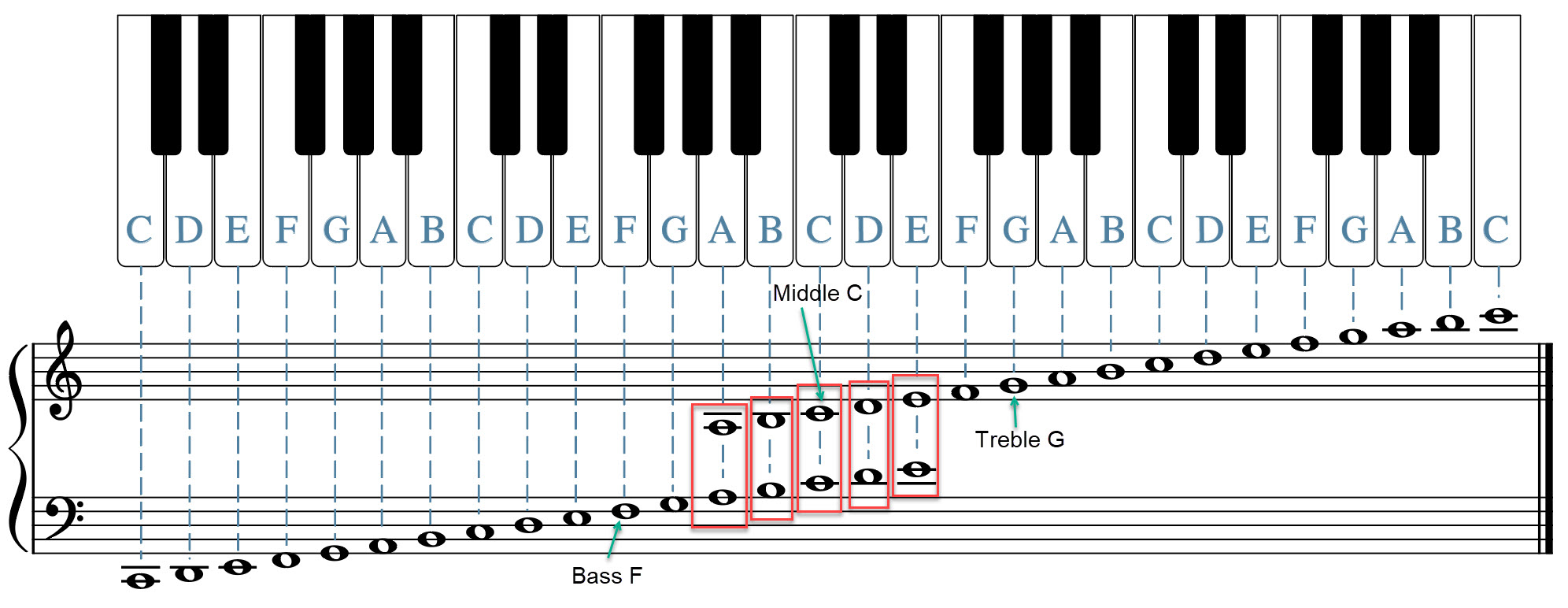

Viewing the piano keyboard in relation to the staff pitch space.

Lecture Video: The Staff:

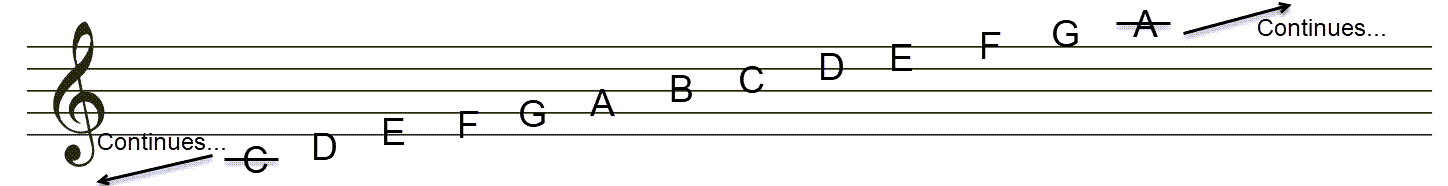

Treble and Bass

In Chapter 1, we learned the names of the pitches; now we can place them on the staff. To do that we need a clef, which is the first symbol that appears at the beginning of every music staff and acts as a reference marker. It is very important because it tells you which note (A, B, C, D, E, F, or G) is found on each line or space. For example, a treble clef symbol tells you that the second line from the bottom (the line that the symbol curls around) is “G”. On any staff, the notes are always arranged so that the next letter is always on the next higher line or space. The last note letter, G, is always followed by another A.

The pitch names of the Treble Clef.

The lines going through the first C and the last A are not “strikeout” marks, but are called ledger lines (discussed below), which extend the staff lines.

The lines going through the first C and the last A are not “strikeout” marks, but are called ledger lines (discussed below), which extend the staff lines.

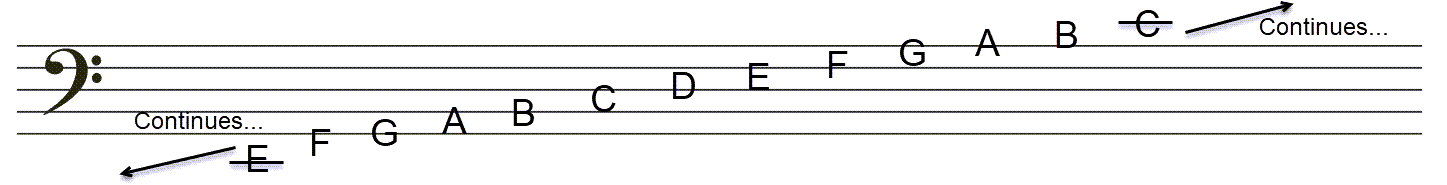

A bass clef symbol tells you that the second line from the top (the one bracketed by the symbol’s dots) is F. The notes are still arranged in ascending order, but their placement has shifted from that on the treble clef; that is, on the Treble clef, the middle line is called B, but on the Bass clef, the middle line is called D.

The pitch names of the Bass Clef.

Concept Check

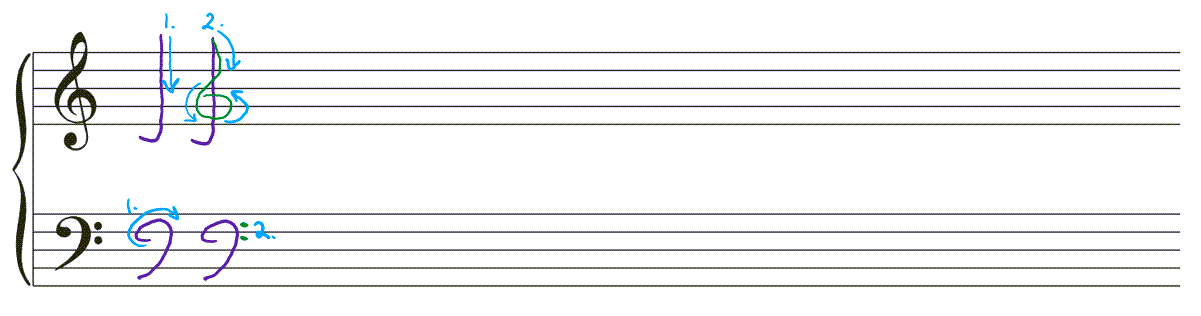

Example 2-1: Practice writing the Treble and Bass clefs, at least 4 each. [Note: This Concept Check does not need an Answer Key, but subsequent ones will include it.]

You can format and create blank staff paper here: https://www.blanksheetmusic.net/ Then you can print or screen capture it to write on with pencil or epen with digital software.

Ledger Lines

Extra ledger lines may be added to show a note that is too high or too low to be on the staff. Ledger lines extend the staff from 5 to 6, 7, 8, etc. lines. They can be added above or below the existing staff. Examples above, C and A on the Treble clef; E and C on the Bass clef. Since they are literally extending the staff, their spacing between lines should be exactly the same as the spacing inside the original staff, but they are only a pitch-width line.

Lecture Video: Clefs:

Clefs and the Piano

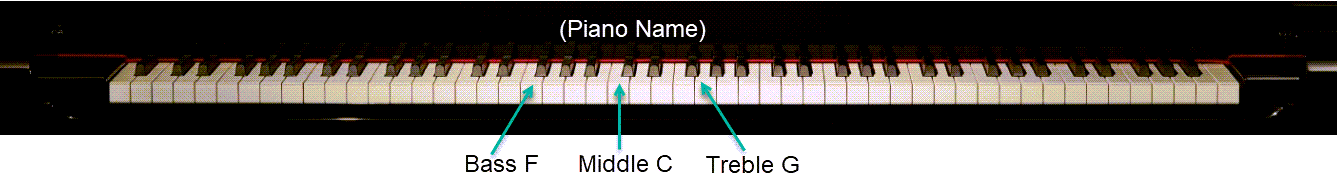

Now let’s place the Treble and Bass clef pitches on the Piano, so we have a reference point about what range they represent. A regular piano has 88 keys (total, black and white)–that’s a very large range–just over 7 octaves. In the middle of that range, you will usually see the brand name of the piano:

The location of the Bass Clef F pitch, Middle C pitch, and the Treble Clef G pitch.

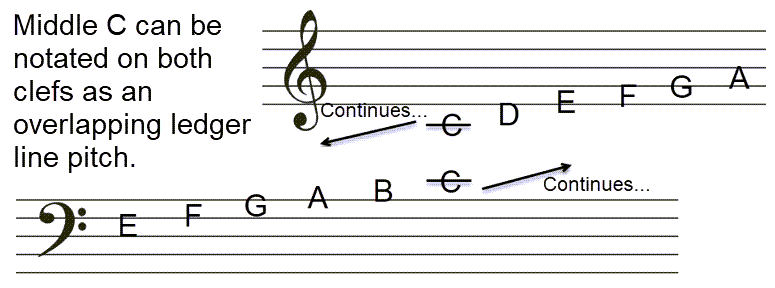

The notes of the clef correspond to specific places on the piano. As you can see below, Middle C (like “home position” on a computer keyboard) can be written as a lower ledger line on the Treble clef and an upper ledger line on the Bass clef. Middle C is in the middle of the piano as well as the middle of the grand staff, below.

The placement of Middle C in relation to the Treble and Bass clefs.

Combining the Treble and Bass clefs creates a Grand Staff–this is the clef used for piano music (yes, pianists read two clefs at once). The Treble generally represents the right hand; the Bass represents the left hand. The grand staff allows there to be overlap, through ledger lines, as you can see below.

The Grand Staff in relation to the piano keyboard. The middle set of pitches, from A to E (red boxes), are examples of pitches that can be “borrowed”–written on either clef. They are literally the same pitch on the keyboard.

Memorizing the Notes in Bass and Treble Clef

This is critical to the rest of the course! One of the first steps in learning to read music in a particular clef is memorizing where the notes are. Your instructor will provide flashcards, online drills, and other materials on Canvas to help with this. It may seem counterintuitive, but I recommend that you forget any tricks you might have heard of like FACE, Every-good-boy-does-fine, etc. You need to develop instant, visual, one-step recognition. If you memorize them with a trick, you will never truly learn them, and all of the other concepts in the course will be more difficult to get through.

Sharp, Flat, and Natural Symbols

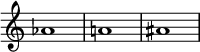

In Chapter 1, we discussed the accidental names and basic symbols on the keyboard: b = flat; # = sharp. Now we need to add those to the clefs, but also need a symbol to “cancel out” a flat or sharp and make it clear when a pitch should go back to its generic version–this is called a “natural” sign.

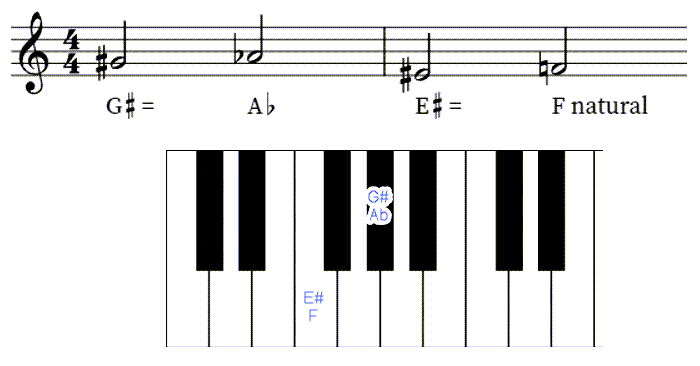

Sharp, flat, and natural signs appear in front of the note that they change.

Notice, when written on the staff, accidentals always go on the left side; when written as a label the accidental goes on the right side, as pronounced: D# or D sharp. The “natural” version of the note is just the pitch class or white key on the piano.

- A sharp sign refers to the pitch that is one half step higher than the natural note.

- A flat sign refers to the pitch that is one half step lower than the natural note.

- A natural sign is used to cancel out a sharp or flat sign when it is used temporarily.

Bonus

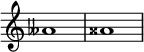

While pretty rare, double accidentals are also possible. They are used in special cases of intervals and chords, used in later theory courses. A double flat just uses two flats next to each other. A double sharp can be written the same (two sharps adjacent), or it can use a special symbol that looks like an X. The double flat does not have a shortcut symbol.

When you need to go back to a single accidental, you need to show one of them cancelled, and one still active—this is true for double sharps and flats:

Lecture Video: HS, WS, and Accidentals:

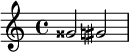

We already covered enharmonic pitches in Chapter 1, but let’s cover them now on the staff.

Enharmonic pitches on the keyboard and the staff.

Lecture Video: HS, WS, and Enharmonicism:

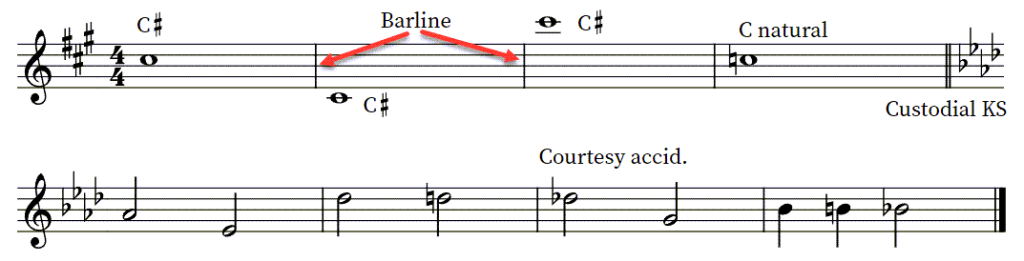

Sharp and flat signs can be used in two ways: they can be part of a key signature (covered in detail in Chapter 4) or they can mark individual notes. As shown just below, a key signature acts as shorthand to tell a musician to make every pitch with those accidentals altered in that way. In the example below, every F, C, and G would be made the sharp version–that saves a lot of ink and time! Pitches that are not in the key signature can be changed individually with accidentals in specific places. Accidentals allow composers to change pitches temporarily in the music. An accidental that is not in the key signature lasts until a) another accidental changes it; b) or the barline cancels it. We’ll see how this works more in the rhythm chapters, when barlines are covered.

The key signature alters all pitches included in it, e.g., all C’s are sharp unless marked as accidentals. The custodial KS alerts the musician that the KS is changing. Barlines cancel out accidentals, but courtesy accidentals are expected to remind the musician. In the last measure, the flat is required to change back from the natural sign inside the measure. An accidental that is not in the key signature lasts until a) another accidental changes it; b) the barline cancels it. We’ll see how this works more in the rhythm Chapters 3A and 3B, when barlines are covered.