Main Body

Musical “Space”

Let’s begin with the piano keyboard because most of us have some familiarity with a piano: no names yet–just a beginning visualization of how music operates [Here’s a useful online piano: https://www.musicca.com/piano. There are also lots of free piano apps for your phone.]

The Piano Keyboard.

The keys (buttons) represent one of the most important concepts of music—pitch—which refers to a label for a distinct musical sound, which could be a letter name, like “D”, or a solfege (which you might know some already) such as “Do” or “Re” or “Fa.” Pitches are like the musical equivalent of colors in a painting; we use them to create melodies of songs (and several other concepts we’ll learn about).

In physics, Pitch has a mathematical definition, a frequency, that a guitar string or air column (like inside a trumpet) vibrates at. A piano hammer strikes the “A” string and makes it vibrate at 440 times per second (called “hertz”), which makes the air molecules vibrate at the same rate, which then makes our eardrum vibrate at the same rate, and our brain perceives, “A.”

As far as our brain is concerned, psychologists call pitch a “categorical perception,” which is a technical way of saying that our brains like to fit things into boxes so we can process them quickly (this is true of many things, like faces, animals, cars, etc.). When it doesn’t fit the categories that we’re familiar with, it “sticks out” to us, i.e., someone singing “off-key.”

Lecture Video, Pitch:

Range in music refers to a span of pitches; we also qualify ranges in terms of “high” and “low.” We can refer to a person having a high range, that the overall span of pitches that they can sing is relatively high. We can also talk about a song having a high range, that the overall collection of pitches fit in a high range. You can change the effect of range on your car stereo by changing the Treble (high) and Bass (low) controls.

We have a natural sense of high and low already–adults’ voices are lower than children’s voices (particularly before puberty), because the vocal folds of children (the small muscles in your larynx that you use to speak and sing) are much smaller (shorter and thinner) than an adult’s. This is generally true of why men’s voices are often lower than women’s (though not always)–the folds are longer and somewhat thicker. This is an acoustic principle, similar to an instrument string length and thickness; this is also why your voice drops in pitch when you get a cold–the mucus makes the vocal folds thicker, so the pitch is lower (a little gross, but true).

When adults and children sing together (“Happy Birthday,” etc.), they are often not literally singing the same pitch (frequency) when singing the same song, but we don’t consider it to be two different songs, and we naturally handle this range difference without any thought. This range difference is called an Octave Interval and is fundamental to every culture’s music, and is the musician’s term for the distance between two pitches. Joy to the world, is a series of small intervals going down the melody; the ABC song, starts with a leap – a larger interval moving up, then a smaller interval up, then it descends by small intervals.

Back to the piano: on the keyboard, high is to the right, and low is to the left. Try this now on your own keyboard, or right here at this website: https://www.musicca.com/piano

Try to find pitches that you can sing, and move up and down a key at a time to feel the high and low difference.

This continuum of sound that we use to construct melodies with, is broken up into discrete pitches. Discrete means separate and measurable; this is another way of thinking of categories. You can think of musical space as “sliced up” into pitches that we use to sing and even speak (some languages are very “tonal,” and depend more on pitch for meaning).

The piano keyboard is divided, firstly, into groups of black and white keys; this is for visual clarity by providing high contrast. Notice that there is a group of two black keys, then a group of three black keys, repeated. Surrounding these groups are the remaining white keys.

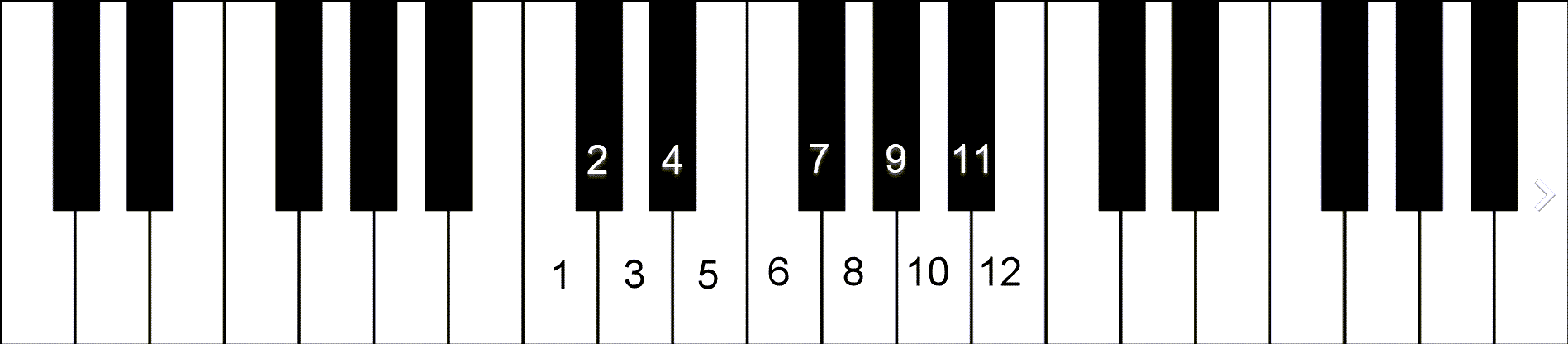

If you count from any key (including all keys, black and white) and then count up (to the right) to that same key (with the same group of surrounding patterns), you will count 12 keys. For example, start on or near the group of two black keys (it doesn’t matter which key you press, just end right before it) and count up all the keys–both colors: be sure to include the first key you count, but don’t recount that same key at the end–and you will get 12. Each move from one key to the next is called a step—kind of like walking up a set of stairs.

An example of 12 pitches in an octave.

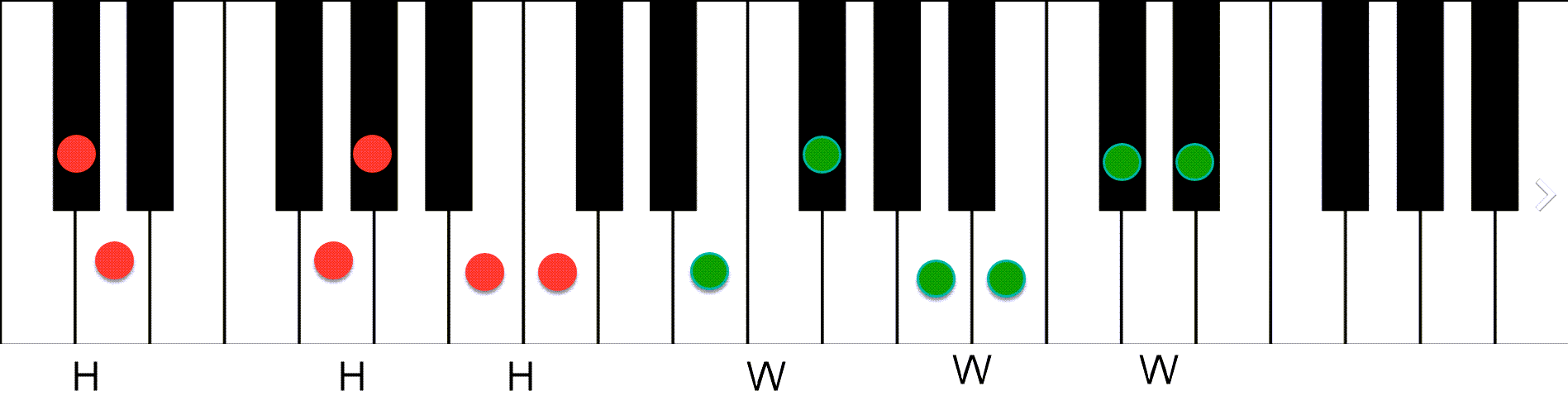

Half steps and Whole steps

Each key (step) on the keyboard–no matter the key color–is called a Half step. This is the smallest interval in our system of music. From one key–pitch–to the next (up or down), regardless of color, is a Half step Interval. Two HS intervals make a Whole step Interval (just like a fraction ½ + ½ = 1). Another way to think of it visually is that any two keys with one key in between them make a whole step. You might be wondering if there is such a thing as a 1/4 step, or maybe even an 1/8th step? Yes, there are. Quarter steps are actually common throughout music history and today in other world music. Western music used to have 1/4 steps more commonly, but not for some time since equal-tempered tuning (and its precursors) became the standard tuning. This made all 1/2 steps the same size and the standard smallest step.

Examples of Half steps (H) and Whole steps (W) on the keyboard. All of the red dots are a half step apart; the green dots are all a whole step. Note all the possible combinations of key colors

Pitch Names

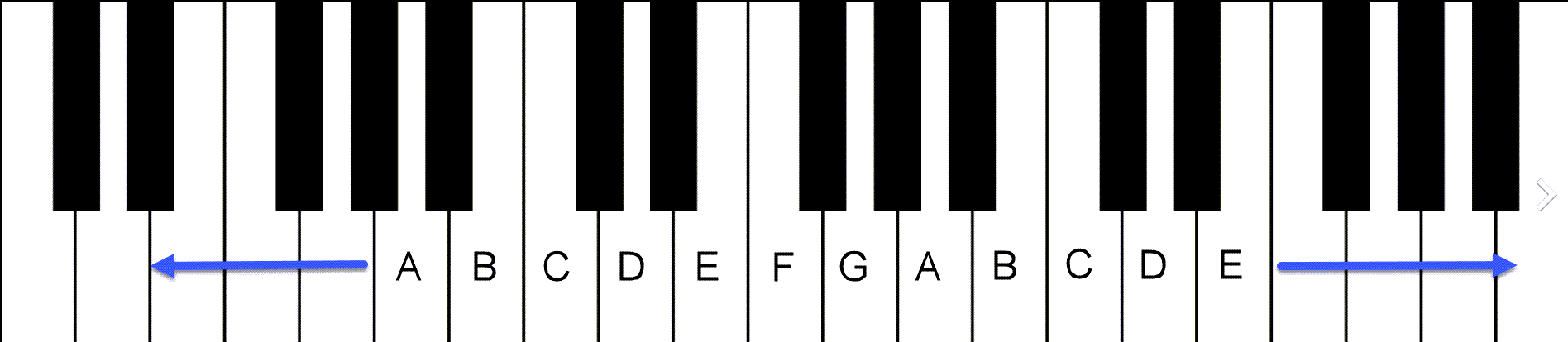

Alright, let’s put some labels to the keyboard. Seven letter names (the first 7 of our alphabet) are used to create the basic categories of pitch labels: A B C D E F G. On the piano, these provide the labels for the white keys on the piano, as below (note: the colors of the keys is part psychological–visual contrast perception–and part historical accident; at various times, the key colors were reversed).

The piano keyboard with pitch-category labels. There are only seven basic pitch letter name categories that repeat across the range of the pitch space. On the piano keyboard, they establish the key names.

You can also see where the term Octave is derived: two of the same pitches are eight pitch names apart. Similarly, the distance–interval–between any other two pitch names is equivalent to how many numbers they are apart. So, referring to the keyboard just above, any A up to the next C (or C down to A) is a “3rd” = three letter names: A, B, C (right) or C B A (left). A few more examples (remember, up/higher is to the right and down/lower is to the left):

- B up to D / D down to B = 3rd

- C up to A / A down to C = 6th

- F up to B / B down to F = 4th

RULE: The number of letter names equals the interval number. This stays consistent, even when we start adding additional details to intervals.

Lecture Video, Pitch Details:

Lecture Video, Pitch and the Keyboard:

Accidental Pitch Names

We’ve already been using the black keys to create our three intervals of half, whole, and 1.5 steps, but how are those keys labeled? Most simply, they are labeled as alterations of the generic pitch names. Musicians call these “accidentals,” which is a little confusing because they sound like a mistake–they aren’t. “Accidental” comes from an old Latin-derived word, and the best modern translation is really “alteration.”

As we noted the half and whole steps, we counted total half steps from any starting key, regardless of the key color; however, to reference the pitches we are talking about, we need to use a letter label plus an alteration, depending on direction. The importance of this will become more apparent in Chapter 2, when we use all of these pitch concepts on the musical staff, in notation.

For now, let’s go back to the general idea that on the keyboard, moving to the right goes higher and moving to the left goes lower. If I move up by a half step, musicians refer to that as going “sharp;” if I move down by a half step, we call it going “flat.” You’ve likely experienced this when listening to an amateur singer (think about various renditions of the “Star Spangled Banner” that don’t go too well), and the singer is struggling to stay “on pitch” with the melody–either singing too high or too low. [Note! While this is a case of a musician making a mistake, remember, this is not why accidentals are called that–again, it’s just an old Latin word referring to an alteration.]

Musicians want a way to identify these pitches precisely–and when it’s not a mistake!–so we apply the concept of sharp and flat to specific pitch names, intentionally. Let’s go back to “sharp” and “flat” that we just mentioned. They have symbols to identify them: a flat (moving lower by a half step) uses a lowercase b and a sharp (moving higher by a half step) uses a # sign (it wasn’t originally a # sign, but it’s close enough).

On the keyboard, this means referring to the black keys as an alteration of the generic letter name, depending on which direction it was altered, as shown here:

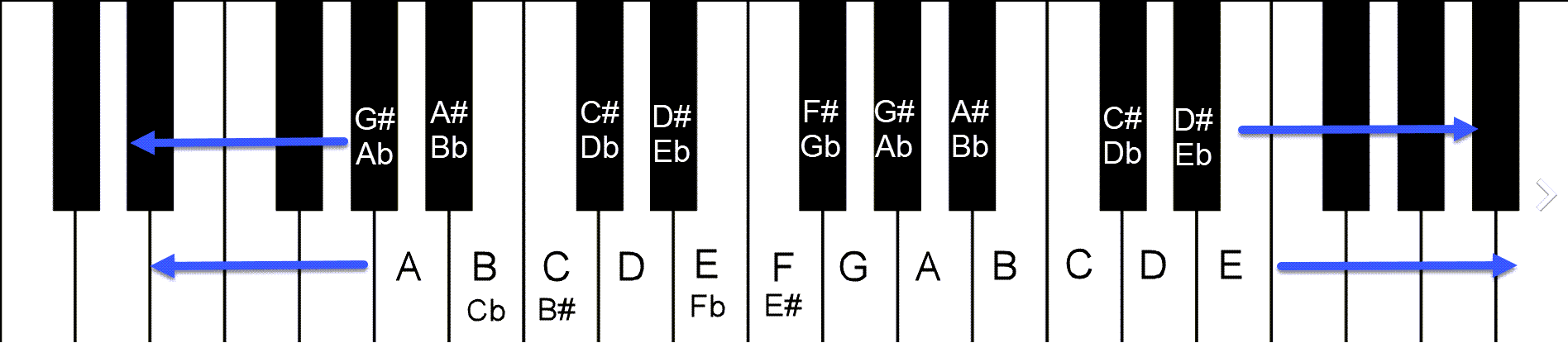

Keyboard with enharmonic pitch names. Note that Cb/B# and Fb/E# are fairily rare, but technically correct in certain contexts.

You might be thinking, “So you can have two different names for the same key on the piano?” Yep, that’s right. “Since your finger is pushing the same button, why do this? Isn’t that a little confusing?” Both good questions. We will look at why more when we do scales in more detail, but for now, the quick answer is it depends on the context. When musicians talk to each other and write music for one another, it can matter how you label and notate pitch names. Think of it in terms of homonyms in language: there, their and they’re sound exactly the same, and you don’t know the difference unless you see it written, or understand the difference by hearing it in context. In music, we call this concept of two labels for the same pitch enharmonic.