Main Body

Scale Types

You’ll remember from our earlier discussion of pitch, clefs, and the keyboard that we only have seven pitch class names: A-G. In order to get 12, we have to use the accidentals. We already explored the Pentatonic (5 note) scale, so this chapter will expand that discussion. You are already likely familiar with the most common scales using those 7 note names in most of the music we know–the “Major” and “Minor” scales. Simply sing “Joy to the World,” and you are singing a descending version of the Major scale; sing “Greensleeves” (“What Child is This?”), and you are singing the Minor scale.

Using the primary notes of a scale, whether it’s the main 5 or 7 notes, is called diatonic. If you add other notes from outside that scale, it is called chromatic (from the 12 total notes). The other notes in the chromatic scale are (usually) used sparingly to add interest or to (temporarily) change the key in the middle of the music. These terms will be important as we move forward looking at scales and, eventually, how to build melodies from them. Before looking at them in detail, let’s explore one other scale that sets a good backdrop for the Major and Minor scales.

The Chromatic Scale

The major pentatonic already showed us how to divide an octave into various interval sizes. The Chromatic scale shows one more way.

The scale that goes up or down only by half steps is the chromatic scale; it plays all the notes on both the black and white keys of a piano. It also plays all the notes easily available on most Western instruments. (A few instruments, like trombone and violin, can play pitches that aren’t in the chromatic scale, but even they usually don’t.) Since there are many enharmonic choices in a chromatic scale, musicians have some expectations about how they are spelled.

1) ascending chromatic scales and passages in music typically use natural and sharp notes and descending use natural and flat notes. 2) When there is a choice between the B-C, E-F enharmonic half steps, choose the natural version (i.e., if possible, avoid E# for F, B# for C, Fb for E, Cb for B). 3) For a scale or passage that starts on a flat note, use flats and naturals for the ascending as well. These are basic guidelines that favor making things consistent and easier for the performer to read; composers make other choices based on context.

Look & Listen!

You can also experiment with a Chromatic Scale using the Google Music Lab here: https://musiclab.chromeexperiments.com/Song-Maker Under the settings, select the Chromatic Scale.

Tonal Center

As we discovered with the pentatonic scale, a scale starts with the pitch that names not only the scale (“G pentatonic”), but also something called its “key.” This note is the tonal center of that key, the note where music in that key feels “at rest.” It is also called the tonic, and it’s the “do” in “do-re-mi” (called solfeggio or solfege, for short). Using the term “key” is a practical way for musicians to talk about all of the pitch “parts” that go into a piece of music: the tonic note, the scale, the chords (coming soon!), and how they all work together to create the melody and harmony. In addition, as in Jazz and Pop music, this gives them a convenient way to talk about improvising–embellishing a song in real-time. Analogously, sports fans will talk about the offense or defense to refer to all of the players, plays, and strategies that they encompass.

For example, musicians will talk about being “in the key of A major” (or any other key), so that song will focus on the pitch A in many ways that we will learn about, such as melody, the harmonies, etc. will return to the note A often enough that listeners will know where the tonal center of the music is, even if they don’t realize that they know it.

Concept Check

Example 4-1: Listen to these examples. Can you hear that they do not feel “done” until the final tonic is played? Each example will have a noticeable pause in the music and then play a final chord. The music right before the pause should sound unfinished–unresolved–and then the last chord should sound finished–resolved.

Example 1:

Example 2:

Major Keys and Scales

Music in a particular key tends to use only some of the many possible pitches available; these notes are listed in the scale associated with that key. They also give a strong feeling of having a tonal center, a pitch that feels like “home” in that key. The pitches that a major key uses tend to build bright-sounding melodies and harmonies that accompany the melody. These bright-sounding melodies and harmonies are what give major keys their “pleasant” moods (these are really subjective terms, but they generically work).

Concept Check

Example 4-2: Listen to these excerpts. Can you tell which is which are major and which are minor by listening?

A)

B)

C)

D)

Major Scale Construction

To find the rest of the notes in a major key, start at the tonic and go up following this pattern, shown below. These major scales all follow the same pattern of whole steps and half steps. They have different sets of notes because the pattern starts on different notes, just as we learned in building different pentatonic scales.

Look & Listen!

All major scales have the same pattern of half steps and whole steps, beginning on the note that names the scale—the tonic.

Listen to, and sing along with, all three scales. Note that 1) they all hold the same pattern; 2) D major sounds/feels–when you sing–higher than C major, and Bb major sounds/feels lower than C and D.

Concept Check

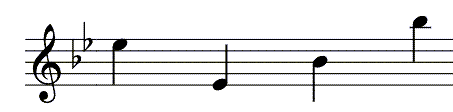

Example 4-3: For each note below, write a major scale, one octave, ascending or descending, as directed, beginning on the given pitch. Remember, Major scales are diatonic, so they can only use one type of accidental.

Begin on F4, ascending ![]()

Begin on G5, descending ![]()

Begin on Ab4, ascending ![]()

Begin on A3, descending ![]()

Begin on Cb3, ascending ![]()

Key Signatures

In the examples above, the sharps and flats are written next to the notes. In common notation, the sharps and flats that belong in the key will be written at the beginning of each staff, in the key signature. This is a shorthand notation, rather than rewriting the accidentals for every occurrence of a pitch that requires it.

The key signature comes right after the clef symbol on the staff. It may have either some sharp symbols on particular lines or spaces, or flat symbols, again on particular lines or spaces. In standard keys, accidentals are never mixed within the key signature. If there are no flats or sharps listed after the clef symbol, then the key signature is “all notes are natural.” Clefs and key signatures are the only symbols that normally appear on every staff. They appear so often because they are such important symbols.

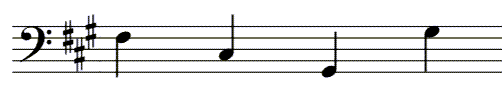

Key Signatures. In the first, all Es and Bs would be played as Ebs and Bbs; in the second, all Fs, Cs, and Gs would be played as F#s, C#s, and G#s. Key Signatures affect all pitches of that pitch class, regardless of octave.

The sharps or flats always appear in the same order in all key signatures. This is the same order in which they are added as keys get sharper or flatter.

Flats: B E A D G C F Sharps: F C G D A E B

(Notice that they are simply the reverse of one another.)

On the staff, they look like this – complete key signatures for both clefs, flats and sharp keys. This is the standard way to notate them – do not alter it.

Key Takeaways

1) It’s important to remember that the order does not change: three flats will always begin with B, E, A–you can not have a three-flat major key signature with, say, A, D, G; this is same for the sharps. [Some later avant-garde composers used alternate KS, but these are the typical ones.]

2) As a rule, do not repeat the accidentals already in the key signature—this will be confusing to the musician and is extra work for you. However, if a pitch is altered by an accidental to change it from what is in the key signature, then it is standard to place a courtesy accidental, when the note is changed back to the key signature, as a reminder to the player.

It is very important to memorize the key signatures. It will make your musical life with scales and chords much easier (and for other musical concepts as well). The easiest way to do this is to simply memorize them with flashcards. There are only 15 major keys. That’s it—it’s not like trying to memorize protein synthesis! Many people like to use the circle of 5ths to help memorize; that’s ok, but I still think that it ultimately creates more work, because you have to remember the order of the entire circle–avoid creating layers to your memorization.

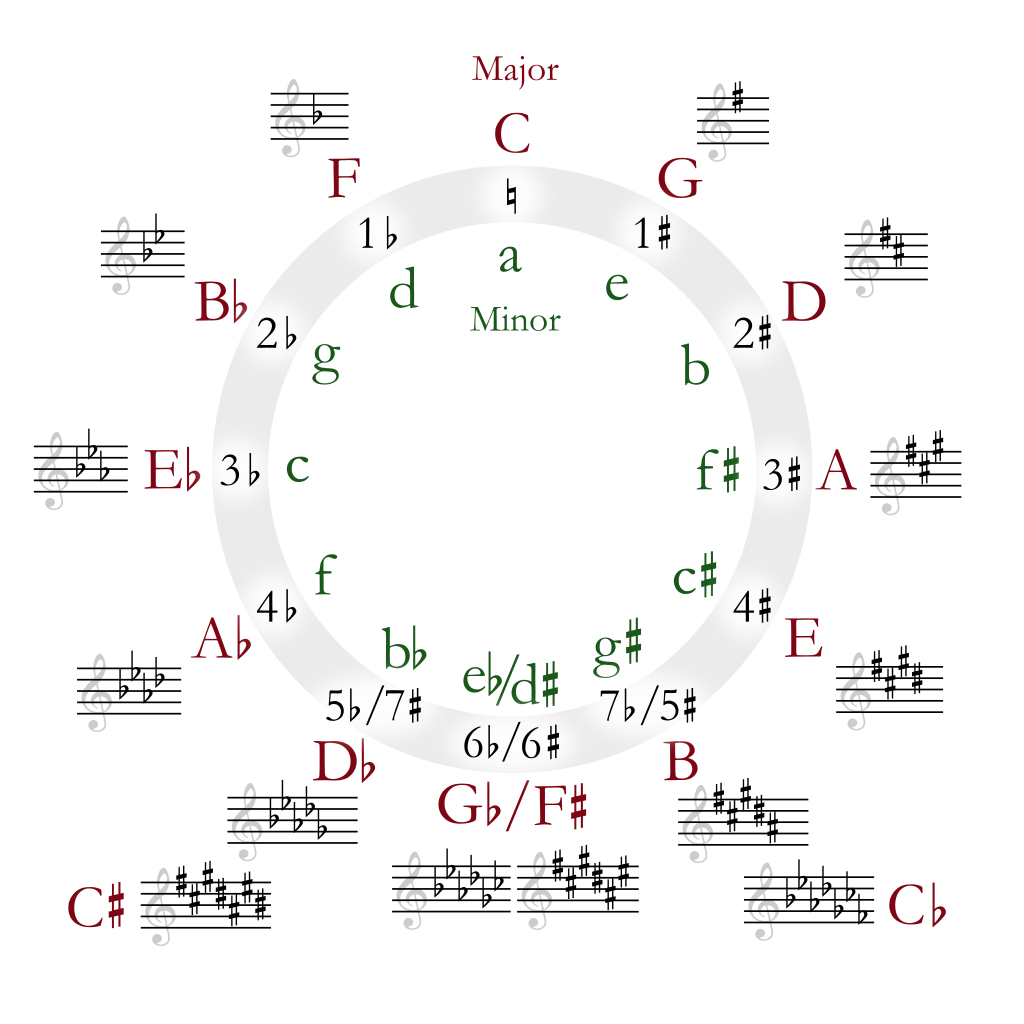

The Circle of 5ths. The Major keys are on the outside (upper case); the Minor keys (discussed later in this chapter) are on the inside (lower case). Notice the overlap of 3 enharmonic keys at 5, 6, 7, o’clock.

Concept Check

Example 4-4: Practice writing the key signatures for the following major keys: D, Eb, B, Cb. Use the full key signature chart from above. You will notice a pattern that each clef and group of sharp or flat accidentals follow. After the first accidental, sharps go “down-up-down, etc.” and flats go “up-down-up, etc.”

Music in Different Keys

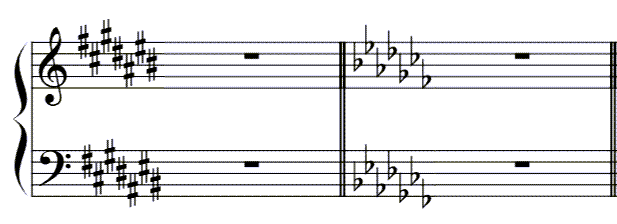

What difference does a “key” make? Since the major scales all follow the same pattern, they all sound very much alike. The same tune looks very different written in two different major keys, but will sound, relatively, the same. Here is a folk tune (“The Saucy Sailor”) written in D major and in F major.

Look & Listen!

The music may look different, but the only difference when you listen is that one in F major sounds higher than the other. Why bother with different keys at all? Most importantly, choosing a particular key is easier to sing or play in that key compared with another. In addition, before equal temperament became the standard tuning system, major keys sounded more distinct from each other than they do now. Even now, there are subtle differences between the sound of a piece in one key or another, mostly because of differences in the timbre of various notes on the instruments or voices involved. Try singing a simple song starting on a lower pitch, and then again on a much higher pitch–notice how the quality of your voice changes.

“Key” Takeaway (pun intended)

Musicians often talk about pieces being “in” a key. This is their way of mentally collecting together all the materials that they will use in that piece: scales (Ch. 4), intervals (Ch. 5), chords (Ch. 6), harmony (Ch. 7), and melody (Ch. 8). That’s right, it means a lot to them! Whether they are learning, memorizing, or improvising music, understanding scales and keys is very important to understanding how tonal music (pop, jazz, classical) works.

Minor Keys and Scales

Music that is in a minor key is sometimes described as sounding more solemn, sad, mysterious, or ominous than music that is in a major key.

Minor scales sound different from major scales because they are based on a different pattern of intervals. Just as it did in major scales, starting the minor scale pattern on a different note will give you a different key signature, a different set of sharps or flats. Complicating the minor scale somewhat, there are three different versions of a minor scale (we’ll get there soon). The scale that is created by playing all the notes in a minor key signature is a natural minor scale. It’s a real nuisance, but the word “natural” here does not refer to the accidental; we’ll explain more after building the scale.

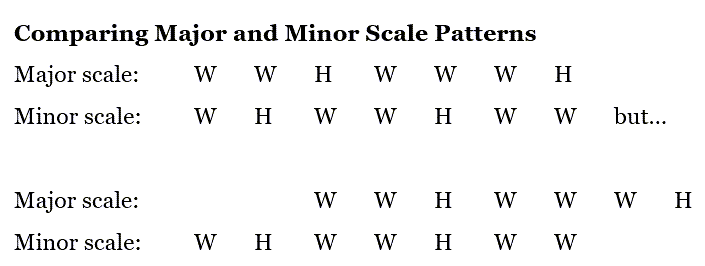

To create a natural minor scale, start on the tonic note and follow this interval pattern:

Look & Listen!

Concept Check

Example 4-5: For each note below, write a natural minor scale, one octave, ascending or descending, as directed.

A Minor, ascending ![]()

G Minor, descending ![]()

Bb Minor, ascending ![]()

G# Minor, descending ![]()

Relative Minor and Major Keys

As with Major keys and scales, it is important to memorize the minor key signatures as well. Notice that in the Circle of 5th’s that each minor key (lower case, inside) shares a key signature with a major key (upper case, outside). A minor key is called the Relative Minor of the major key that has the same key signature (and vice versa, the major key is the Relative Major to the minor). Even though they have the same key signature, a minor key and its relative major sound very different. They have different tonal centers (tonic pitch), and each will feature melodies, harmonies, and chord progressions built around their respective tonal centers. It is easy to predict where the relative minor of a major key can be found. Notice that the pattern for minor scales overlaps the pattern for major scales. In other words, they are the same pattern, but starting in a different location in the scale.

The interval patterns for major and natural minor scales are the same WH pattern, but starting at different points.

The Relative Minor scale begins on the 6th scale degree of a Major scale; conversely, the Relative Major scale begins on the 3rd scale degree of the Minor scale. The Eb major and C minor scales start on different notes, but have the same key signature, making them related keys:

Look & Listen!

Why is the label “natural” used? As mentioned earlier, there are actually three types (varieties) of minor scales, as we will see below. For right now, the important point about the Natural minor scale is that what makes it natural is that after you have established the correct pitches using the pattern, and have the correct Key Signature, all of the notes are natural to that key. In other words, you do not need accidentals added to make it minor once you have the correct key signature – it is natural to that key signature.

Here’s a chart to summarize how relative keys work with regard to the Tonic and the Key Signature. We will expand this chart after the next section on Parallel Keys.

Table comparing relative keys.

| Tonic | Key Signature | |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Keys | Different | Same |

Concept Check

Example 4-6: What are the relative majors of the minor keys in Concept Check, Example 4-5?

Parallel Major and Minor Keys

Another way of “traveling” between Major and Minor keys is through a Parallel relationship. In this case, the tonal center (tonic pitch) of the keys/scales is the same. Consider the C major scale below–to create its parallel minor scale, lower the 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees, which would make Eb, Ab, and Bb:

Key Takeaways

Recall that the relative example we just looked at shows a scale in two different keys (tonal centers), and the effect is a higher or lower pitch, which can be 1) to make it easier for a singer to perform (range); 2) give a different “feel,” timbre, to the melody based on who (singer) or what instrument is performing it. Switching to a Parallel key creates this shift without changing the tonal center: C major and C minor share the same tonic pitch, so the melody will not sound higher or lower. Making this change to the Relative minor would create the dramatic “mode”[3] shift—between major and minor—and the tonal center change.

Tabel comparing Relative and Parallel Keys.

| Tonic | Key Signature | |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Keys | Different | Same |

| Parallel Keys | Same | Different |

Here is the ABC song demonstrating the concepts, first in D major, then in the parallel D minor, then back in D major, and finally in the relative minor, B minor.

Look & Listen!

Concept Check

Example 4-7: Recreate the Major scales from Example 4-3, Step 1) using a Key Signature, and then Step 2) create the parallel natural minor scale with added accidentals by the correct pitches.

Begin on F4, ascending ![]()

Begin on Ab4, ascending ![]()

Begin on A4, descending ![]()

Harmonic and Melodic Minor Scales

All of the scales above are natural minor scales. They contain only the notes in the minor key signature. There are two other kinds of minor scales that are commonly used, both of which include notes that are not in the key signature (hence, not natural to the key signature).

The harmonic minor scale raises the seventh note of the scale by one half-step, whether you are going up or down the scale. Harmonies in minor keys often use this raised seventh tone in order to make the music feel more strongly centered on the tonic, and to affect certain harmonies (Chords, Chapter 6). As you listen to the Harmonic Minor scale, you’ll notice two things: 1) the raised 7th scale degree does help push the ear towards the tonic note; 2) a “gap” is created between scale degree 6 and the altered, raised scale degree 7—it’s our old friend, step and a half, which we first encountered in the Pentatonic scale. In this context, it really stands out; composers felt the same way, and wanted to “smooth it out” when creating melodies, leading to the Melodic Minor scale.

In the melodic minor scale, the sixth and seventh notes of the scale are each raised by one-half step when going up the scale (ascending), but return to the natural minor when going down the scale (descending). If you compare the top half of a melodic minor scale to its Parallel Major scale, you’ll see that they are the same notes. Melodies in minor keys often use this particular pattern of ascending and descending accidentals (but not always), so instrumentalists find it useful to practice melodic minor scales in this way.

Listen & Look!

Concept Check

Example 4-8: Recreate the Natural Minor scales from Example 4-7, using a Key Signature, and then create the Harmonic or Melodic minor scale, as directed.

A Minor, Harmonic ascending ![]()

G Minor, Harmonic descending ![]()

F Minor, melodic–asc. and desc. ![]()

Scale Degree Names and Functions

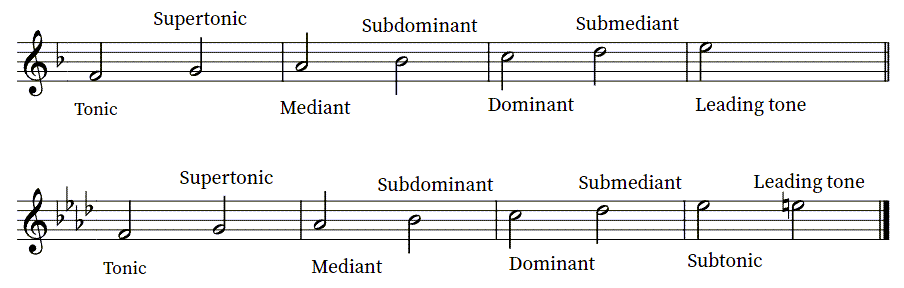

Musicians commonly refer to scale degrees by number and by name. These names have certain “functions” associated with the scale degree, and how it “acts” in a key. For example, the Leading Tone, the 7th scale degree, sounds like it needs to resolve (lead) to the first scale degree.

The names of the scale degrees: examples show F major and F minor – the only practical difference that minor has two 7th scale degree names for natural 7th and harmonic 7th.

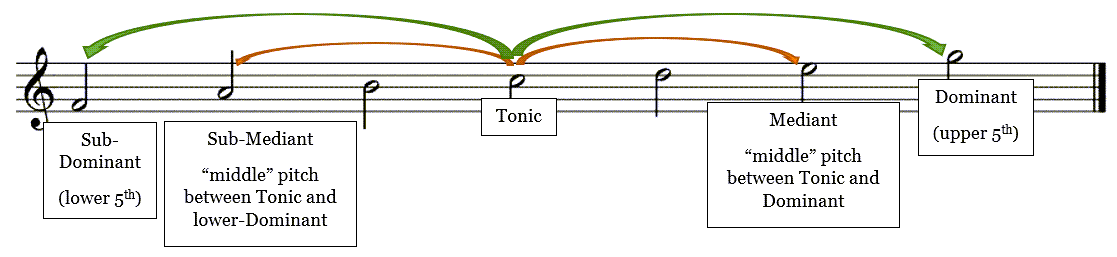

The Tonic is the center of the scale in importance and sound–it’s “home.” The interval of the 5th is also very important in Western history (as shown, in part, by the Circle of 5th’s). The Dominant scale degree is considered the second-most-important scale degree of a key in understanding the progression of musical melodies and harmonies. The symmetry of the scale was also important in history, and the Subdominant gets its name not from being one step below the Dominant, but by being the “under” dominant to the Tonic, as shown below: the symmetry of the 5th above and the 5th below.

Functional derivation of the degree names. The symmetry of

This also explains the Submediant name; the Mediant is the “middle” (Latin) of the 5th interval between Tonic and Dominant. Therefore, the 6th scale degree is the Sub–lower 3rd interval between Tonic and the Subdominant. The Supertonic is literally “above” (Latin super) and the lowered 7th scale degree is Subtonic. Leading tone, as discussed, has a strong tendency resolving towards the Tonic.