Main Body

Understanding Meter In-Depth

The meter of a piece of music is the arrangement of its rhythms in a repetitive pattern of strong and weak beats–we were discussing this while looking at Time Signatures in Chapter 3A. This does not necessarily mean that the rhythms themselves are repetitive, but they do strongly suggest a repeated pattern of grouped pulses. It is on these pulses–the beat of the music–that you tap your foot, clap your hands, dance, etc.

Some music does not have a meter. Ancient music, such as Gregorian chants; new music, such as some experimental contemporary music, and various other World music, may not have a strong, repetitive pattern of beats. Other types of music, such as Indian music, may have very complex meters that can be difficult for the beginner to identify.

But most Western music, especially since the Baroque style period, has predictable, repetitive patterns of beats. This makes meter a very useful way to organize the music into measures, marked off by bar lines. These help the musicians reading the music to keep track of the rhythms.

Let’s clarify some terms before proceeding:

Table of Rhythm and Meter Terms and Definitions

| Pulse | Like the pulse in your body, pulse in music refers to any periodic (regularly recurring) sound. |

| Accent | Stressing one or more of these pulses. Typically, this is done by playing them louder, but can be stressed in other ways: agogic (length), range (a higher/lower note that stands out from surrounding pitches). It can be a regular accent (metrical) or irregular (syncopated–discussed later). |

| Grouping | Assigning a pattern to the accents that groups a particular number of pulses together. |

| Beat | The technical name for pulses when they have an accent pattern that groups them into a metrical pattern (meter). NOTE: This definition of beat is called Metrical Beat. This is how composers communicate their musical intention to performers through the use of a Time Signature, Tempo markings (the speed of beat value), and other notational means. Performance beat is how musicians interpret the notation in performance, which can have some flexibility. |

| Division | How the beat is divided, either into 2 or 3 (there can be other divisions, but they are beyond this course). |

| Subdivision | A further division of the division into 2. There can be other ways of subdividing, but they are beyond this course. |

| Levels of Beat | Beat, Division, Subdivision all refer to levels of beats within a meter. You can tap your foot, dance, conduct, etc. to any of these levels–that is the point of performance beat–how you feel the music. Technically, musicians generally need to agree on which level they are performing a piece of music. |

| Time Signature | The notated expression of a meter. This does not limit the performance beat interpretation; it makes it practical, though, for musicians to be able to interpret a composer’s intentions. Meter and Time Signature are often thought of on a practical level as synonymous, but it’s important to note that they are not, technically, the same. |

| Tempo | The speed of music. Musicians communicate this in talking about the speed of the beat. When you hear a musician giving a “count-off,” they are telling the other musicians the tempo. More precisely, in notation, there are two ways to specify a tempo. Metronome markings are absolute and specific, e.g., ¼ = 132 bpm (beats per minute). Other tempo markings are verbal descriptions that are more relative and subjective. Both types of markings usually appear above the staff, at the beginning of the piece, and then at any spot where the tempo changes. |

| Conducting | Beyond the scope of this course (take Music 5 if you’d like to learn how!), but has some related concepts that help illustrate meter. Conducting depends on a combination of the meter beat and the performance beat of the piece; conductors use different conducting patterns for the different meters. These patterns emphasize the differences between the stronger and weaker beats to help the performers keep track of where they are in the music. Regardless of what pattern the conductor is doing, the performers may interpret the pattern in a different way to help them understand a passage better. Conversely, a conductor may choose to conduct a time signature with a different pattern from the time signature in order to make it easier for the ensemble to perform. |

Even though the time signature is often called the “meter” of a piece, one can talk about the meter without worrying about the time signature or even being able to read music. This is how many singers, who don’t read music, are able to participate in choirs: they listen to others and follow the general contour of the written music.

If you’re curious, here is a series on conducting basics by Leonard Slatkin: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL2_S0hFw3zDl47TtV7iYbu—XhiuSrkgaW We also cover conducting in Music 5.

Classifying Meters

Grouping Numbers

Meters can be classified by counting the number of beats from one strong beat to the next. For example, if the meter of the music feels like there are two primary beats, it is in duple meter; three is triple meter, and four is quadruple. The first beat of any meter is always considered the strongest, and the rest, relatively weak.

Duple Meter: 2 strong beats (Strong, Weak)

Triple Meter: 3 strong beats (Strong, Weak, Weak)

Quadruple Meter: 4 strong beats (Strong, Weak, Strong, Weak)

[Take a look and listen back at Concept Check 3-3, 4 in Ch. 3A to refresh on how these meter patterns work and sound.]

Simple and Compound Meters

Meters can also be classified by the Division of the Beat, as either Simple or Compound. In a simple meter, each beat is divided into two. In compound meters, each beat is divided into three. This distinction has some very practical implications for how to perform a piece of music.

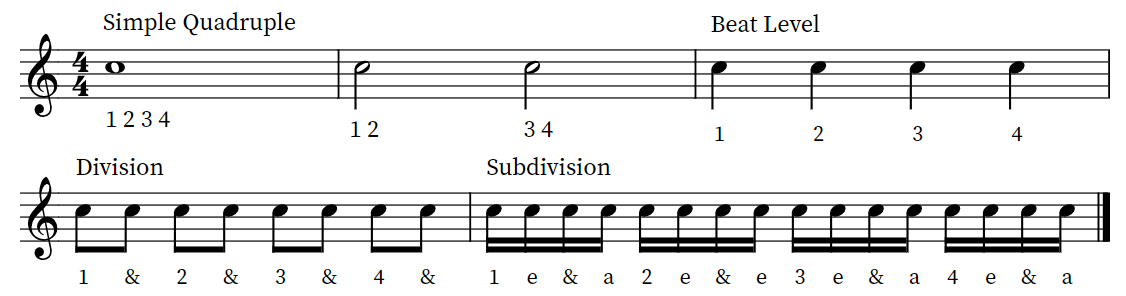

Simple Meter: Let’s look at this excerpt below, which shows a ¼ note meter, starting with a whole note, taking up 4 beats, the 2 half notes taking up another 4, and then the four beats themselves. The last measure continues the division of the beat, i.e., each ¼ note divided into two 1/8th notes (the counting is included, and will be covered in detail shortly):

The basic components of Simple Meter.

Counting Simple Meters

Musicians need a practical way to figure out and perform complex rhythms in real time, as well as communicate to other musicians how a particular rhythm should be performed, if there is confusion. In order to assist in this, they have developed counting systems. There are actually multiple counting systems that different musicians favor, somewhat depending on culture or style, but in the US, most musicians learn a system called “1 e + a” (when handwriting notation, the + sign is used, pronounced “and”; with some notation systems, like Noteflight, the & sign is used).

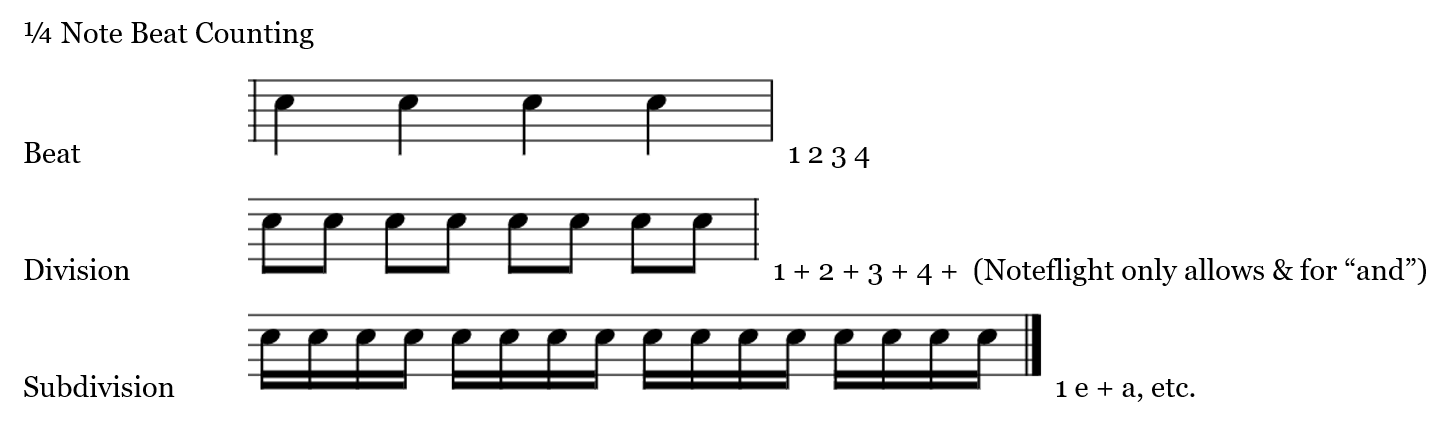

Counting patterns for Simple Meters with a ¼ note beat value. These patterns apply to 2/4, 3/4, 4/4.

Look & Listen!

An example of some common Simple Meter patterns, including the counting as it would look written in. The counting for each note and rest is included, but I have also included additional counting under certain notes to show they contain all the beats and divisions.

Here are some of the most common Simple Meter rhythm patterns, with counting, for 2/4, 3/4, 4/4. Remember! Rests can replace any of these notes, and the counting would not change, but the performance would.

Look & Listen!

Compound Meters

The easiest way to understand compound meters is to think of them as a modification of a Simple Meter, for example, this Simple Duple rhythm. The top voice shows the ¼ note Beat, and the bottom voice is the Division.

Basic division of a Simple Meter beat.

This shows 2 beats per measure, and each beat divided into 2. Compound means that the Beat is divided into 3 instead of 2. In order for this to mathematically work, we have to use a dotted note for the beat, per the definition above. This is the most important thing to remember about Compound meters: the Beat is always a dotted note. Now, let’s “compound” the above rhythm.

Basic division of a Compound Meter beat.

The ¼ note beat is turned into a dotted ¼, and following our rule of dotted notes, each dotted 1/4 = 3, 1/8 notes. Now, how do we write that as a time signature? It would be nice if time signatures would simply show exactly what they mean, for instance:

![]() would be written as

would be written as ![]()

That would mean that the compound example we just created would be ![]() But that’s not how the system works.

But that’s not how the system works.

Can we write it as ![]() ??

??

Sorry, but no; therefore, for Compound meters, even though the Beat is always a dotted note value, since we can’t write that as a number with a dot, we have to write what the division value is. [This is an example of a holdover from an earlier system. Our rhythm notation system comes from a much older (centuries old) system, parts of which have stuck around from practice.] Two dotted 1/4 notes equals six, 1/8 notes, so that is what we right for the time signature.

Basic Compound Meter beat is expressed in the time signature as the number of divisions, rather than the number of beats.

Counting Compound Meters

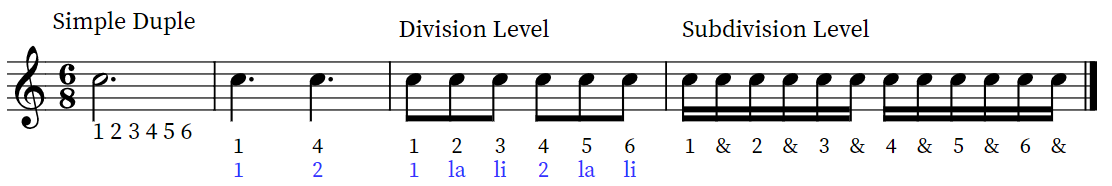

Counting patterns for Compound Meters with a dotted-¼ note beat value. The blue counting is an alternate system of counting. Counting the actual beats in 2 is fairly common (m. 2); however, using the alternate syllables of “la and li” (m. 3) is not as common. We will use this counting for a special notation (triplets) covered below. There are additional syllables for the subdivision level that are not commonly used.

Many musicians will count Compound meters in more than one way, depending on the tempo. Once a musician is comfortable with how the rhythmic patterns work in compound, they can leave out many aspects of the counting, and focus on larger structures. There is also another system of counting that uses alternate syllables, but is not as popular and is more cumbersome.

For this course, we will use the simpler approach, which simply counts up the number of notes given in the time signature, which for compound means, technically, the division note. This style of counting is common with many musicians, as it simply treats compound time signatures as any other, i.e., counting up the given note value in the time signature.

Here are the most common Compound Meter rhythm patterns:

Look & Listen!

Additional Rhythm Concepts

Ties & Slurs

Tied notes add value by connecting two values together. Ties are written with a curved line connecting two notes that 1) are the same pitch; 2) are adjacent. Notes of any length may be tied together, and more than two notes in a row may be tied together. The sound they stand for will be a single sound (i.e., the first tied note begins the sound, with no re-articulations) that is the length of all the tied notes added together. This is another way (in addition to the dot) to make a variety of note lengths.

There are two reasons for a tie:

- To lengthen a note past a bar line. No measure can have more value than allowed, so to lengthen the last note of a measure past that limit, then you have to use a tie to connect the to the value in the next measure.

- To show where a note value crosses a beatline within a measure. This is not always necessary (you can sometimes use a dotted note), but makes it easier to see where each beat begins.

Both of these criteria need to be true for it to be a tie. If not, then it is a slur, which is an articulation (Ch. 8), and has nothing to do with rhythm. Ties get confused with slurs, but they are not related at all. A slur connects two or more notes with different pitches. These examples demonstrate the difference.

- Each note is articulated–“struck” (called an “attack” by musicians).

- with ties, only the first note of each tied pair is articulated.

- letter B, but with a Slur added–this slur does not affect the Tie. A Slur is an articulation, and tells the performer about how to play the note attacks (smoother, more connected), and does not affect rhythm.

- a tie used within a measure–the tied 1/8 note ends beat 2, and the tied 1/4 note begins beat 3–the tie makes the start of beat 3 easier to see.

Recognizing Meters

To learn to recognize meter, remember that (in most Western music) the beats and the subdivisions of beats are steady, underneath the changing, actual musical rhythm. You are basically listening for a constant, even pulse underlying the rhythms of the music. For example, if it makes sense to count along with the music “ONE-and-Two-and-ONE-and-Two-and” (with all the syllables very evenly spaced) then you probably have a simple duple meter. But if it’s more comfortable to count “ONE-and-a-Two-and- a-ONE-and-a-Two-and-a”, it’s probably compound duple meter. Make sure numbers always come on a beat (as opposed to an offbeat), and “one” is always on the strongest beat.

NOTE: The strongest beat of any meter is the first, usually called the downbeat, because the conductor always marks this with a downward motion.

This will take some practice if you’re not used to it, but it can be useful practice for anyone who is learning about music. To help you get started, the figure below sums up the most-used meters. To help give you an idea of what each meter should feel like, here are some examples:

2/4—Elgar March:

3/4—Mozart Sonata:

4/4—Mozart Sonata:

6/8—Greig Peer Gynt:

https://youtu.be/XHg87IL3B2s (this is a computer version, but the score is easier to follow. Please listen to the actual symphonic version here: https://youtu.be/-PYOKT5yODg)

To compare the idea of Duple meter, but contrasting Simple with Compound, listen to the Elgar march above, again—Simple Duple—and then listen to the Sousa March below–Compound Duple. Both clearly have a TWO feeling.

6/8—Sousa March (note the clear 2 feel):

Borrowed Divisions: Triplets and Duplets

Dots and ties give you much more freedom to write notes of varying lengths, but so far you must build your notes from halves of other notes, i.e. ½ fractions or 2:1 ratios. If you want to divide a note length into anything other than 2:1 or 4:1—if you want to divide a beat into thirds or fifths, for example—you must write the number of the exceptional division over the notes.

These unusual subdivisions are called borrowed divisions because they sound as if they have been borrowed from a completely different meter type. They can be difficult to perform correctly and are avoided in music for beginners. The only one that is commonly used is triplets, which divide a note length into equal thirds. For example, the division in 2/4 would be 2, 1/8th notes, so the easiest way to think of a triplet is that you are “cheating” and putting three 1/8th notes (in this example) where there should only be two.

Since you are not slowing the tempo of the beat down, that means you have to speed up the triplet division notes. This mean that they mathematically go from 1/8th notes to 1/12th notes! (Don’t worry, musicians don’t usually talk about 1/12th notes.)

Look & Listen!

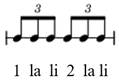

Musicians are (somewhat frustratingly) not very consistent in how they count borrowed divisions. For triplets, options range from: “tri-pl-et”; “1-2-3”; “1 + a”; “1 la li”; “1 ti ta”. For purposes of homework and quizzes, we will use the “1 la li” counting to distinguish them.

We will use the “1 la li” method of counting for triplets in this course.

In a compound meter, which normally divides a beat into three, the borrowed division may divide the beat into two, as in a simple meter, and this is called a Duplet. Basically, this is the opposite effect of the triplet: you slow down the speed of the duplet notes to fir the entire dotted beat note. The counting for a Duplet is most simply handled by borrowing the counting from the equivalent simple rhythm/meter, so two 1/8 notes against the beat would be 1 +, which is simple enough to use.

Look & Listen!

Syncopation

Syncopation is one of the more fun and interesting aspects of rhythm, but it’s extra tricky to understand at first, and can also be fairly difficult to learn how to perform. Syncopation comes from the word syncope, which in medicine means “to faint”; it refers to a loss of blood pressure. Its Greek root refers to “cutting something short”–like blood flow. What does this have to do with music? Well, think about a very popular concept from house music–“dropping the beat.” The rhythm is setup, giving us an expectation, then it’s withheld–cut short–creating tension, and then “dropped,” creating a satisfying resolution.

A syncopation or syncopated rhythm is: any rhythm that puts an accent (emphasis) on a beat, division, or a subdivision of a beat, that is not usually accented. Therefore, syncopation is primarily a way of accenting a note on an unexpected beat or part of a beat. There are multiple ways to accent notes, creating the syncopation:

- Register—accenting a note by placing it unexpectedly high or low.

- Value—accenting a note on a weaker beat (or portion of a beat) by using a longer rhythmic value that lasts through a stronger beat (or portion of a beat). This is also called agogic accent.

- Tie—this is the same effect as Value, but is created with a tie instead; however, it’s a very common technique, because it’s easier to see the hidden beat.

- Accent marking—placing a specific accent notation mark over a note to tell the player to make a note stand out by playing it louder.

Syncopation always involves the relationship between at least two notes, even though musicians may refer to a syncopated note (singular). They say this for clarity to one another while working out a performance idea, i.e., it’s usually one note that needs “fixing”, but the concept only means something in the flow of the surrounding notes. For example, listen to this melody a couple times, and be sure to tap your foot on each 1/4 note beat the second time through–feel the syncopation at the red notes.

Look & Listen!

- The first measure clearly establishes a simple quadruple meter (1+2+3+4+), with beats one or three as the primary beats. But then, in measure two, a syncopation happens; the longest and highest note (register accent), marked in red, is on beat two, normally a weaker beat; additionally, the ½ note length (value accent) lasts through beat three, obscuring the stronger beat.

- In the syncopation in measure three, the longest note, marked in red, doesn’t begin on a beat; it begins halfway through the third beat, lasting through the 4th beat (value accent).

Another way to strongly establish the meter is to have the syncopated rhythm playing in one part of the music while another part plays a more regular rhythm, as in this passage from Scott Joplin from Peacherine Rag. Notice that the syncopated notes in the melody come on the second and fourth fractions or subdivisions of the beat, essentially alternating with the strong eighth-note pattern laid down in the accompaniment of the bass staff. This shows syncopation created through value accent and by a tie.

Look & Listen!

Listen to the full piece HERE.

Finally, here is an example of an accent mark being used to directly show that an off-beat division value should be accented (2 or 4) or off-beat (&). Be sure to listen a couple times and have the beat well established in order to hear the syncopation.

Look & Listen!

Lecture Video: Syncopation (Note–this is an older video from a prior class using a previous textbook, but the information is the same.): https://youtu.be/SeEGnD9uj1M

Lecture Video: Video Demo: Subdivisions, Triplets, Syncopation: https://youtu.be/dRfyFyQItuo