Main Body

Chords and Keys

Harmonic analysis means understanding how a chord is related to the key and to the other chords in a piece of music. This is so practical that you will find many musicians who have not studied much music theory, and even some who don’t read music, but who can tell you what the “one” or the “five” chord are in certain keys.

Why is it useful to know how chords are related? Many standard forms (for example, the “twelve bar blues”) follow very specific chord progressions, which are often discussed in terms of harmonic relationships.

- If you understand chord relationships, you can transpose any chord progression you know to any key you like, which can make it easier to sing or play.

- If you are searching for chords to go with a melody, it is very helpful to know what chords are most likely in that key, and how they usually progress from one to another.

- Improvisation requires an understanding of the chord progressions.

- Harmonic analysis is also necessary for anyone who wants to be able to compose stylistic chord progressions or to study and understand the music of other composers.

Basic Triads in Major Keys

You can find all the basic triads that are possible in a key by building one triad on each note of the scale. One easy way to name all these chords is to number them: the chord that starts on the first note of the scale is “I”, the chord that starts on the next scale degree is “ii”, and so on.

In classical and jazz theory, Roman numerals (hereafter RN) are used to number the chords. Capital RN are used for major chords and small RN for minor chords. The diminished chord is a small RN followed by a superscript circle o. The augmented chord is a capital RN with a superscript plus + sign (it is not found in the standard diatonic keys).

Look & Listen!

To find all the basic chords in a key, build a simple triad (in the key) on each note of the scale. You’ll find that although the chords change from one key to the next, the pattern of major and minor chords is always the same.

The benefit of RNs is that you can refer to patterns quickly by referencing the RN. Unlike leadsheet symbols, RNs maintain their chord function even when you change keys. This progression of chords: ii V I sounds like the same pattern no matter what key/scale it is in.

Lecture Video, RNs:

Concept Check

Example 7-1

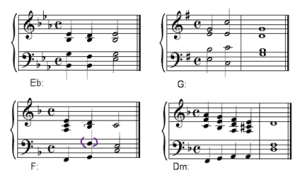

Place the correct key signature then complete all of the triads and the V7 for each, and label each with the correct roman numeral.

Bb Major

Eb Major

Naming Chords Within a Key

Thus far, we have concentrated on identifying chord relationships by number, because this system is commonly used by musicians to talk about every kind of music from classical to jazz to blues. The other set of names that is commonly used, particularly in classical music, are the names of the scale degrees, learned in Chapter 4. As we discussed there, these names are associated with functions of scale degrees, and now the chords that go with them. Function refers to how scale degrees as pitches in a melody and as chords setup certain expectations about where a melody and/or a chord progression will go.

Concept Check

Example 7-2: Name the chord.

- Dominant in C major

- Subdominant in E major

- Tonic in G major

- Mediant in F major

- Supertonic in D major

- Submediant in C major

- Dominant seventh in A major

Basic Triads in Minor Keys

Since minor scales follow a different pattern of intervals than major scales, they will produce chord progressions with important differences from major key progressions.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

These differences are also covered in the video.

Lecture Video, Minor Key RN:

Concept Check

Example 7-3: Write (triad) chords that occur in the following minor keys–place the key signature first. Place the RN below each, reflecting the correct quality–this exercise is based in Natural Minor–no accidentals.

A Minor

B Minor

Concept Check

Example 7-4: Complete the following using Harmonic minor. Place the RN below each, reflecting the correct quality.

G Minor

C# Minor

Lecture Video, Inversions Context (note, this video makes use of the Figured Bass shorthand (5-3, 6-3, etc.), which we are not using, but overall concepts covered are still relevant):

Cadences

A cadence is any place in a piece of music that has the feel of an ending point, and acts like musical punctuation. A musical phrase, like a sentence in language, usually contains an understandable idea, and then pauses before the next idea starts. Some of these musical pauses are simply take-a-breath-type pauses, and don’t really give an “ending” feeling. In fact, like questions that need answers, many phrases leave the listener with a strong expectation of hearing the next, “answering”, phrase. Other phrases, though, end with a more definite “we’ve arrived where we were going” feeling. We’ll listen to several soon!

The composer’s expert control over such feelings of expectation and arrival are one of the main sources of the listener’s enjoyment of the music. Music also groups phrases and motives into verses, choruses, sections, and movements, marked off by strong cadences to help us keep track of them. Here are the primary cadence types, and the chord patterns that create them. The examples below all show three chords for context, but the cadence patterns are comprised of two-chord patterns.

Cadences – Look & Listen

Definitions:

-

- Authentic: A dominant chord followed by a tonic chord (V-I, or often V7-I).

- #1) This is also known as a “perfect” (as in “complete”) authentic cadence when both V and I are in root position and the highest voice has the root over the tonic chord.

- #2) Authentic Cadence with the V inverted—changes sound quality.

- #3) Authentic Cadence with the root of I not in the highest voice at the end—sounds slightly less conclusive.[1]

- Plagal Cadence: A subdominant chord followed by a tonic chord (IV-I). For some people, this cadence will be familiar as the “Amen” chords at the end of many traditional hymns.

- Half Cadence: A cadence that ends on the dominant chord (V); considered incomplete. The chord before—here ii—could be several different chords; the main criteria is that the phrase ends on V.

- Deceptive Cadence: The vi chord is used as a substitute for the I chord (in major or minor key) in what looks like it would be an Authentic cadence.

- Authentic: A dominant chord followed by a tonic chord (V-I, or often V7-I).

Lecture Video, Cadences:

Listen to these examples of all of the above cadences from Robert Hutchinson’s OER text: https://musictheory.pugetsound.edu/mt21c/cadences.html#AuthenticCadence

(FYI: we use much of Hutchinson’s textbook in music 1A, 1B, and 2A.)

Concept Check

Example 7-5: Identify the type of cadence in each excerpt. 1) Analyze the leadsheet of each chord; 2) analyze the roman numeral; 3) label the cadence based on the last two chords, compared with the Cadence examples. [Note: Ignore the F pitch in parentheses in the F major example; this would create a minor 7th chord.]

A Hierarchy of Chords—Chord Progressions

Among the seven chords in a key, some are more likely to be used than others. The most common chord is I. In Western tonal music, I is the tonal center of the music, the chord that feels like the “home base” of the music. In major keys, the other two major chords in the key, IV and V are also likely to be very common.

Whereas the I (tonic) chord feels most strongly “at home,” V7 gives the strongest feeling of dissonance. This contrast is typical for giving music a satisfying ending. Although it is less common than the V7, the diminished viio chord, is considered to be a harmonically unstable chord that strongly wants to resolve to I. Listen to this short progression hear how I is stable and the other chords create various levels of tension compared to I. Listen to these sample progressions:

Look & Listen!

Many folk songs and other simple tunes can be accompanied using only the I, IV and V (or V7) chords of a key, a fact greatly appreciated by many beginning guitar and keyboard players.

A lot of folk music, blues, rock, marches, and even some classical music is based on simple chord progressions, but, of course, there is plenty of music that has more complicated harmonies. Pop and jazz in particular often include many chords with added or altered notes. Classical music also tends to use more complex chords in greater variety, and is very likely to use chords that are not in the key (chromaticism).

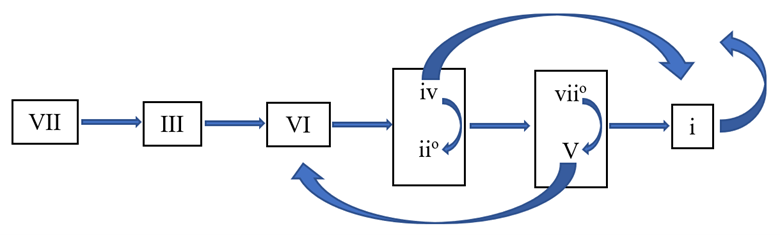

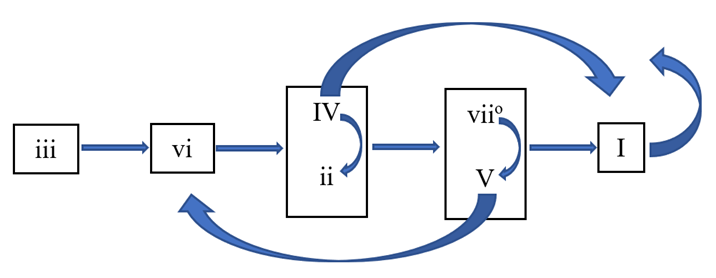

As part of your last composition exercise, you will need to construct a Chord Progression using the following charts. These charts capture the most basic diatonic progressions used a good amount of classical music. Pop songs and jazz tunes are captured somewhat in these charts, but they diverge significantly in many ways (there are other classes to study these). For someone just starting out, they are helpful in coming up with a basic phrase progression, as you will do in the assignment.

TIP: Most pieces will start on the Tonic (I) chord to help establish the key center. The way these flow charts work is not a simple left-to-right: after starting on I–which is like the Queen piece on a chessboard, it can go anywhere–follow the arrows, which can take you left or right, depending on your current chord, until you complete your progression at a cadence.

Progression flow chart for major keys.

Progression flow chart for minor keys.