Main Body

The Shape and Value of a Note

Rhythm is one of the more “natural” parts of music–it’s easiest for people to grasp. We instinctively start to move to certain styles of music–being moved by the “beat.” Dancing is certainly one of the oldest and most ubiquitous activities and customs across cultures and history. While the feel of rhythm is universal, connecting it to notation is definitely not. As with pitch, there is a whole set of new symbols to familiarize yourself with: Chapter 3A focuses on the notational parts of rhythm; Chapter 3B focuses on the application of rhythm.

Unlike other visual arts (like a painting), experiencing music must occur through time, sequentially. How humans experience time is a fascinating study in psychology (also a specialized area of music psychology); how we experience time in listening to, or participating in, music is important to how it should be notated. Feel your pulse–your heart beat. It’s regular (for the most part) and slices up the passage of time: 60 beats per minute when resting on a chair, 140 beats per minute when running fast. Musicians also talk about beat, and they even determine how fast a song should be played by talking about “beats per minute.” Let’s establish some notational symbols, and then dive into the concepts. You’ve already seen some of these symbols used to denote pitches, but now they will be combined to add rhythm.

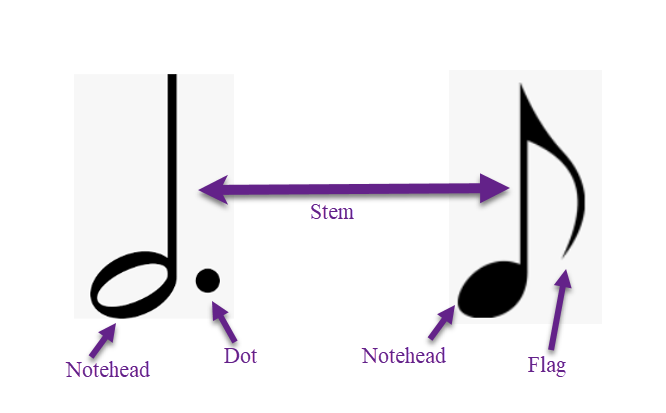

All of the parts of a written note affect how long it lasts. The circle portion, the notehead, does double duty: 1) pitch and 2) rhythmic value, depending on whether it is solid or hollow.

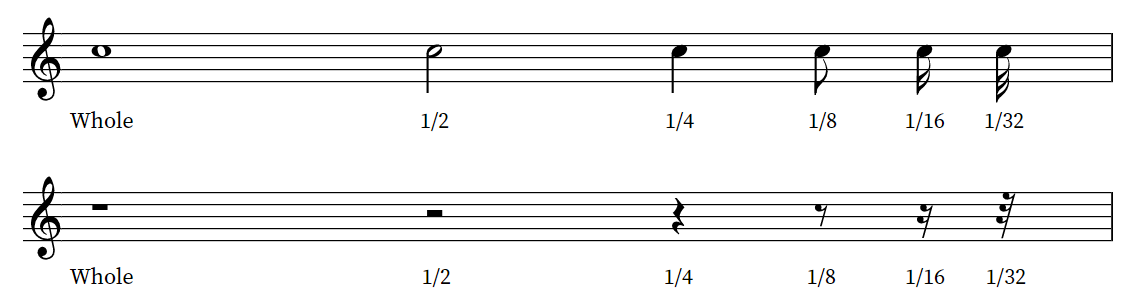

Since music has to occur in time, we need a way of communicating how long each pitch should last. The symbols above have “value” or length in time. The simplest-looking note, with no stems or flags, and an unfilled notehead, is a whole note. All other note values are defined by how long they last compared to a whole note. All other note values are distinguished by the following variables:

- Filled or empty notehead

- Stem or no stem (the whole note is the only one without a stem)

- Flag(s) or no flag

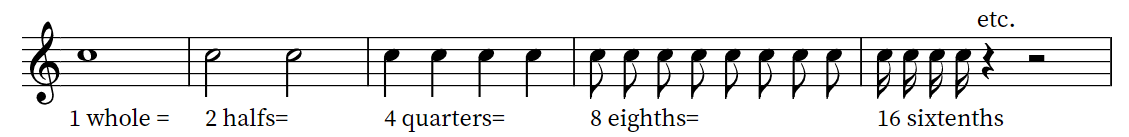

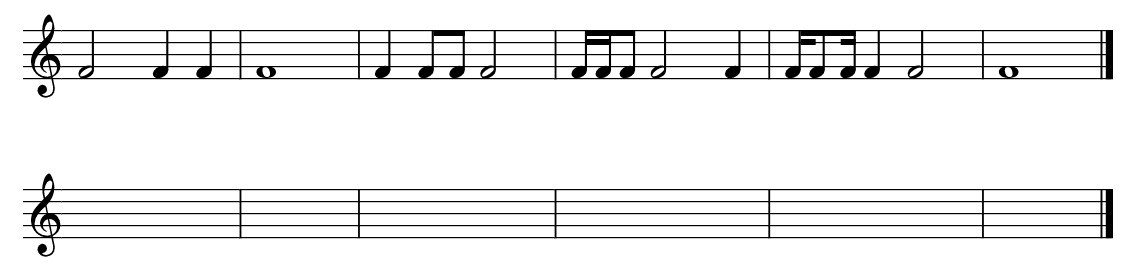

The most common note values.

Note values are proportional. A note that lasts half as long as a whole note is a 1/2 note (the only other note with an empty notehead). A note that lasts a quarter as long as a whole note is a 1/4 note. The pattern continues with 1/8 notes, 1/16 notes, 1/32 notes, 1/64 notes, and so on, each type of note being half the length of the previous type (we won’t go beyond the 1/16th note in this course). In common Western music styles, there are no specific note symbols for 1/3 notes, 1/6 notes, 1/10 notes, etc., but there ways to create unique values.[1]

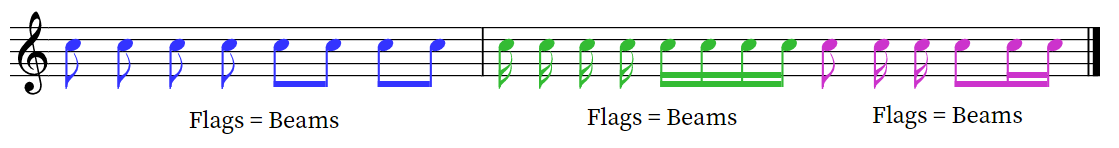

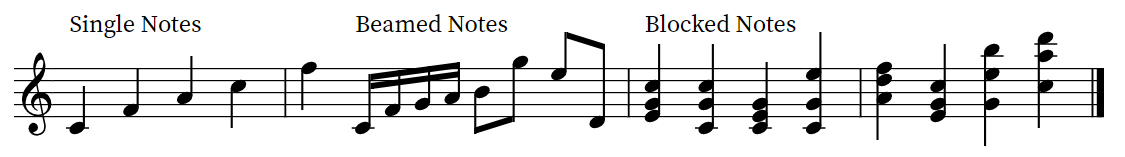

Note lengths work just like fractions in arithmetic: two 1/2 notes or four 1/4 notes last the same amount of time as one whole note. Flags are often replaced by beams that connect the notes into easy-to-read groups.

Notice that some of the eighth notes above don’t have flags; instead they have a beam connecting them to another eighth note. If flagged notes are next to each other, their flags can be replaced by the same number of beams that connect the notes into easy-to-read groups. How these groups work is covered in Chapter 3B.

Beams

The notes connected with beams are easier to read quickly than the flagged notes. Notice that each note has the same number of beams as it would have flags, even if it is connected to a different type of note. The notes are connected so that each beamed group gets one beat. This makes the notes easier to read quickly.

Lecture Video: Note Values, Stems, Beams:

Concept Check

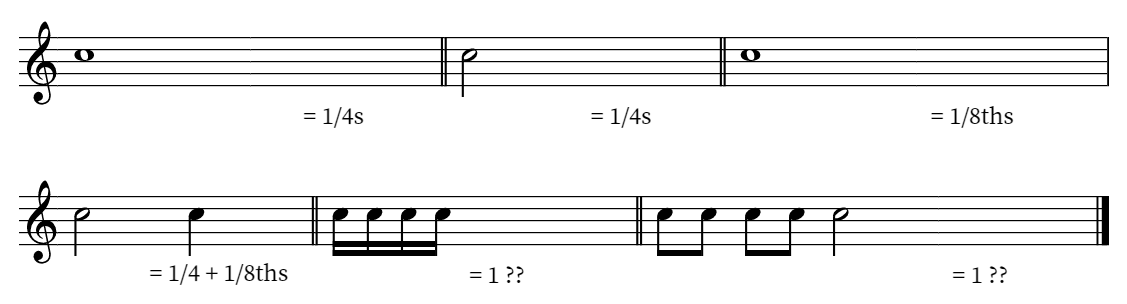

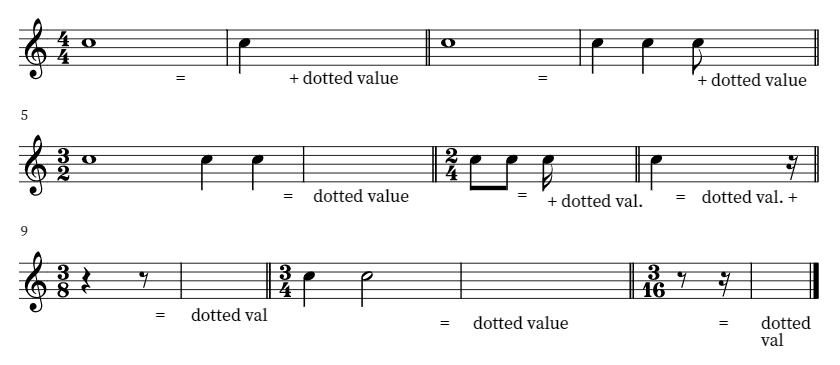

Example 3-1: Draw the missing notes and fill in the blanks to make each side the same duration (length of time).

More about Stems

Whether a stem points up or down does not affect the note length. There are two basic ideas that lead to the rules for stem direction: 1) the music should be as easy as possible to read and understand; 2) the notes should tend to be “in the staff” as much as possible.

Basic Note Stem Rules

- Single Notes—Notes below the middle line of the staff should be stem-up. Notes on or above the middle line should be stem-down.

- Notes sharing stem (block chords)—Generally, the stem direction will be the direction for the note that is farthest away from the middle line of the staff.

Keep stems and beams in or near the staff, but also use stem direction to clarify rhythms and parts when necessary.

Lecture Video: Stems:

Measures and Barlines

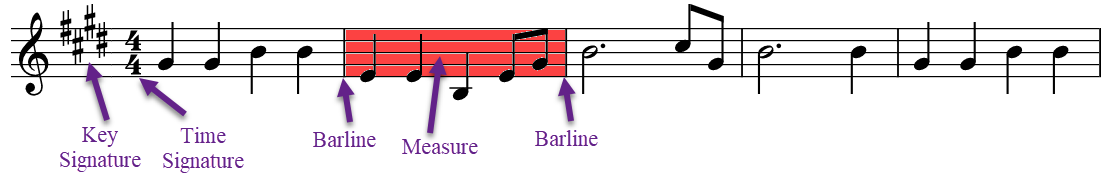

Let’s put together a number of elements that we’ve been discussing in more detail here, as they are used in a musical score, visualized below.

Vertical barlines divide the staff into short sections called measures or bars; these terms are often used interchangeably by musicians, but they are technically not the same. Barlines are the vertical line marking off a measure. A double barline, either heavy or light, is used to mark the ends of larger sections of music, including the very end of a piece, which is marked by a heavy double bar.

Important: Accidentals altering a pitch last only until 1) another accidental changes that same pitch; 2) more commonly, the barline cancels it out. Therefore, most accidentals usually only last for one measure; this is different from the Key Signature (more detail in the Scales chapter), which lasts for the entire piece of music (or until it changes in the middle)!

The most common elements on the staff, always read left to right. The space between each barline is a “measure.”

Duration: Rest Length

A rest stands for silence in music. For each kind of note, there is an equivalent written rest symbol.

The most common note values and their corresponding rest symbols.

The whole and half rests should be written on those specific lines: whole rest hanging on the bottom of the 4th line; half rest sitting on top of the 3rd line.

Concept Check

Example 3-2: For each note on the first line, write a rest of the same length on the second line. The first measure is done for you.

Rests can specify silence in a particular part only as well. On a staff with multiple parts, a rest must be used as a placeholder for one of the parts, even if a single person is playing both parts. When the rhythms are complex, this is necessary to make the rhythm in each part clear.

LOOK & LISTEN: When multiple simultaneous rhythms are written on the same staff, rests may be used to clarify individual rhythms, even if another rhythm contains notes at that point.

Lecture Video: Rests:

Beats and Measures

Because music is heard over a period of time, one of the most important ways that music is organized by thinking of music as comprised of short periods called beats. In most music, things tend to happen right at the beginning of each beat. This makes the beat easy to hear and feel. When you clap your hands, tap your feet, or dance, you are “moving to the beat.” Your claps are sounding at the beginning of the beat. This is also called being “on the beat,” and it is analogous to when the conductor’s baton hits the bottom of its path and starts moving up again.

Concept Check

Example 3-3: Listen to excerpts A, B, C and D. Can you clap your hands, tap your feet, or otherwise move “to the beat”? Can you feel the 1-2-1-2 or 1-2-3-1-2-3 of the meter? Is there a piece in which it is easier or harder to feel the beat?

A

B

C

D

Concept Check

Usually, a pattern can be heard in the beats: strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak, or strong-weak-strong-weak. Beats are organized further by grouping into measures with barlines. For example, for music with a beat pattern of strong-weak-weak, or 1-2-3, a measure would have three beats in it.

Time Signatures

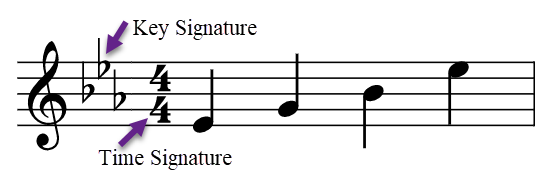

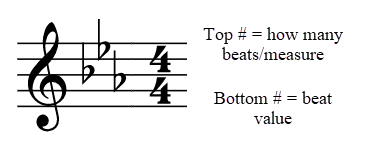

The time signature appears at the beginning of a piece of music, right after the key signature (more on this in Chapter 4). Unlike the key signature, which is on every staff, the time signature will not appear again in the music unless the meter changes. The meter of a piece of music is how its basic rhythm is grouped (more in Chapter 3B!); the time signature is the symbol that tells you the meter of the piece and how (with what type of notes) it is written.

The time signature appears at the beginning of the piece of music, right after the clef symbol and key signature.

The time signature tells you two things: 1) how many beats there are in each measure, and 2) what type of note holds the beat value. Time signatures contain two numbers. The top number tells you how many beats there are in a measure. The bottom number tells you what kind of note holds the beat value.

This time signature means that there are three quarter notes (or any combination of notes or rests that equals three quarter notes) in every measure. A piece with this time signature would be “in three four time” or just “in three four”.

In “four-four” time, there are four beats in a measure and a quarter note is the beat. Any combination of notes or rets that equals four quarters can be used to fill up a measure.

Lecture Video: Time Signatures:

Dotted Notes

What if you want a note (or rest) length that isn’t half of another note (or rest) length? For instance, what if you want to fill an entire measure of three-four meter? A ½ note is too little, a whole note is too much. This is when we use a dot notation.

A dotted note is one-and-a-half times the length of the same note without the dot. In other words, the note keeps its original length and adds another half of that original length because of the dot. A dotted half note, for example, would last as long as a half note plus a quarter note, or three-quarters of a whole note.

Another–and better method–is to realize that every dotted note is equal to three of the next smaller value (i.e., the value of the dot).

Method A is adding the half value—the dot—to the main note. Method B shows the three next-smaller note values that any dotted not is equal to.

Concept Check

Example 3-5: Make groups of equal length on each side, by putting a dotted note or rest in the box.

A note may have more than one dot. Each dot adds half the length that the dot before it added. For example, the first dot after a half note adds a quarter note length; the second dot would add an eighth note length. Double-dotted notes are fairly rare, so we won’t deal with them further in this class.

When a note has more than one dot, each dot is worth half of the dot before it.

Lecture Video: Dotted Notes:

Important NOTE!

BONUS!

Advanced Note Stem Rules

- Notes sharing a beam—Again, generally you will want to use the stem direction of the note farthest from the center of the staff, to keep the beam near the staff.

- Different rhythms being played at the same time by the same player—Clarity requires that you write one rhythm with stems up and the other stems down.

- Two parts for different performers written on the same staff—If the parts have the same rhythm, they may be written as block chords. If they do not, the stems for one part (the “high” part or “first” part) will point up and the stems for the other part will point down. This rule is especially important when the two parts cross; otherwise, there is no way for the performers to know that the “low” part should be reading the high note at that spot.

Keep stems and beams in or near the staff, but also use stem direction to clarify rhythms and parts when necessary.

Alternate Time Signatures

A few time signatures don’t have to be written as numbers. Four-four time is used so much that it is often called common time, written as a bold “C”. [The “C” abbreviation was not originally a letter C, but half of a circle, that was derived from an older notation system.] When both fours are “cut” in half to twos, you have cut time, written as a “C” cut by a vertical slash.

Alternate notation for 4-4 and 2-2 time signatures.